In his erudite and fascinating article, Rabbi Yaakov Bochkovsky examines how changes to the Kollel world’s self-identity have impacted its students and their own sense of purpose. He argues that Kollel, previously a training ground for men aspiring to Torah leadership roles, later evolved into a distinct community, so that participation in it has become an end unto itself.

Rabbi Bochkovsky surveys the challenges attendant to these developments, mostly prominently the weakening of students’ sense of purposefulness and motivation. But he argues that “In parallel with the undeniably growing numbers of Yeshiva graduates going on to higher education and professional careers, there is also a continued vitality within Kollel institutions.” As an example, he notes that “over the past fifteen years, the global ‘Dirshu’ organization has led a revolution in this area. Thousands of Kollel students are tested monthly on thirty folios of Gemara, completing the entire Shas repeatedly.” Accordingly, asserts the author, there is indeed growth and productivity within the Kollel world, challenges notwithstanding. Kollel learning is renewing itself and maturing, paving the way for engagement in a Torah study that is more integrated into daily life. Today’s Kollel students, more anchored in the “real” world, are no longer learning in a bubble of abstract analyses.

Some aspects of these arguments are compelling. Indeed, one cannot deny the welcome development of new learning initiatives, and it is hard to ignore the dramatic growth and evolution of the Kollel community that have facilitated these changes. That said, I do not think these are systemic trends. Rabbi Bochkovsky’s assessment that today’s Kollel student (and hence his learning) is more connected to worldly life does not match reality as I see it. For the most part, Kollel learning still follows the traditional yeshiva style studies and curriculum. Localized initiatives, such as the few he mentions, are but individual efforts; they are not mainstream undertakings and do not indicate significant change in the underlying conception of what it means to be a Kollel student. The Kollel, today as in the past, understands itself as part of the Yeshiva community. While they may not be physically co-located, the Kollel and Yeshiva still occupy a shared ideological space, as I will show below.

To be perfectly clear, I must caveat that any criticism directed here at the wonderful Kollel world derives from deep love and enormous appreciation for the students who devote their lives to Torah learning each and every day. Counting myself among those who have been fortunate enough to spend their days in the beis midrash learning and growing, I speak as an insider who shares this wonderful and unique world, not as an observer from the sidelines. It is important, nonetheless, to engage in reflective thought on the institutions we hold dearest, and to thing about how to improve them and maintain their vitality.

The “Yeshivish” Form of Learning

I was recently invited to participate in a sheva berachos. One of the speakers, a relative of the bride who teaches in a well-known yeshivah, noted that only a generation ago there were but a handful of Kollel institutions, with limited learning opportunities and all following the format of the regular yeshiva system. By contrast, he asserted, a young man today can easily find a Kollel and study what he is most interested in.

At the time, I couldn’t quite put my finger on why his remarks struck me as problematic. But shortly after leaving the gathering, as I reconstructed the speech in my mind, I identified what was irking me. The speaker made two claims that simply don’t match the facts on the ground. First, it is incorrect to suppose that today’s Kollel students easily find places to learn. In fact, Kollel institutions are generally hesitant to accept new students over the age of thirty, and even young Kollel students don’t have an easy time of it.

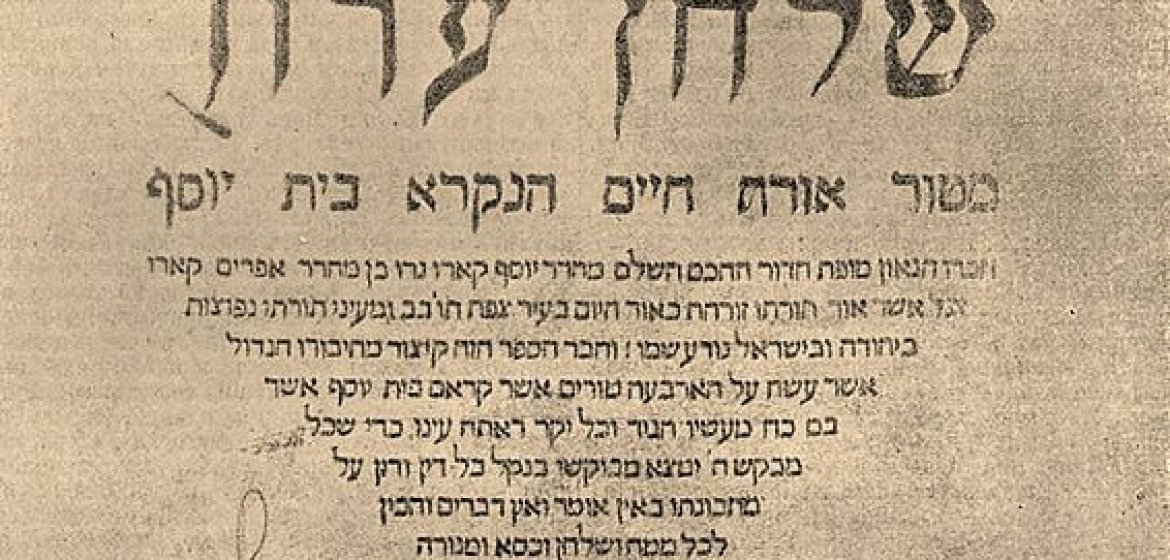

Secondly, and more centrally, I was disturbed by his suggestion that Kollel students may learn any Torah subject they wish. True, some institutions offer such options, and some large institutions, like the Mir, offer a wide array of learning opportunities; but most continue to follow the classic Yeshiva style and curriculum. For example, intensive study of Shulchan Aruch in general, and “Even HaEzer” and “Choshen Mishpat” specifically, is sorely lacking.

According to Rabbi Bochkovsky, a defining feature of the contemporary Kollel generation is the integration of its learning into daily life. One can scarcely imagine a more tangible demonstration of such integration than in-depth, practice-oriented study of Choshen Mishpat and Even HaEzer. In fact, learning these relevant sections of Shulchan Aruch would form a natural culmination of the many years spent in Yeshiva poring over complex sugyos of Nashim and Nezikin. After all, in the Choshen Mishpat section of the Shulchan Aruch, together with its commentaries that are so celebrated in Yeshiva studies, one finds resolution to the debates of Perek HaMafkid and to the nuances of Yesh Nochlin. Having persistently refined the underlying concepts and principles in Yeshiva, students would benefit tremendously from shifting their analysis to a lens of practical application.

And yet, surprisingly enough, even those Kollel men who direct their focus on halacha rarely engage in intensive study of Choshen Mishpat and Even HaEzer. Students who do learn these sections generally do so in the manner customary in yeshiva study: at an exceedingly slow pace and without a commitment to reaching a robust, broad perspective or practical conclusions.

Sadly, a Kollel student who is looking for an intensive structure in which to delve into those sections of Shulchan Aruch that best complement his studies in yeshiva cannot easily find one. While he may be able to secure a seat in a Kollel that affords him the freedom to learn whatever he wishes, such a setting, lacking serious engagement with liked-minded peers, is hardly conducive to long-term success or satisfaction.

Seeing the Goal

I believe there are two separate factors contributing to the state of affairs whereby the most obvious sections of halacha are not being pursued as primary subjects in Kollel.

First, we face a methodological problem. Study of Shulchan Aruch, which must begin with Tur and Beis Yosef, requires command of many sections of Shas. To properly unpack and resolve a halachic question, one must be familiar with all the related and often scattered Talmudic sugyos. Estate law refers to a sugya in Erchin (beyond its primary locus in Bava Basra); a discussion of a minor’s capacity to be party to financial transactions involves discussions in both Gittin and Bava Metzia, and so on. Thus, a wide breadth of knowledge, not common among young Kollel students, is needed to embark upon the intense halacha study track we are proposing.

However, the methodological obstacle can be overcome relatively easily. A “pre-halacha” study track could be developed, whereby the student acquires familiarity with the necessary areas of Shas and learns the basic forms of practical halachic analysis. But beyond this technical fix, we encounter another challenge.

The second issue preventing growth of a robust Kollel framework for studying halacha is ideological. Several years ago, shortly before I began studying for dayanus, I spoke with a noted Rabbi and shared my thoughts about learning halacha. I described my sense of satisfaction from this form of learning and I asked him why more people do not pursue a halacha track in Kollel. Was it attributable to the differences in style between studying halacha and Gemara?

In response, the Rabbi stated that our community, the Charedi, yeshiva-oriented community, does not believe it is correct to learn Torah for the sake of reaching a goal. Studying Shulchan Aruch, in a goal-oriented fashion that is likely to engender feelings of completion and accomplishment, might run counter to the ethos of lifelong learning lishma, for the sake of Torah itself. Accordingly, the slow pace of yeshiva study is not an inexplicable peculiarity. Rather, it is driven by the idea that Torah study is endless, one’s singular lifelong focus, not a series of study units to be duly finished. It is a feature, not a bug, that yeshiva and Kollel learning is not oriented towards goals and concrete objectives.

It took me some time to appreciate that his comments reflect a view very commonly held in the Kollel community and its leadership. Rabbi Bochkovsky takes pride in the Kollel student who embodies that lofty ideal to “dwell in the G-d’s house all the days of my life.” Study of halacha with an eye towards its practical application is an entirely different approach to learning, one that runs contrary to the animating spirit of our community’s Kollel life.

We might suggest then that in its evolution from a training ground to a final destination all its own, the Kollel has perpetuated the yeshiva’s modes of study and curriculum. An approach to learning that does not impose tangible goals is appropriate for young students who spend many years in yeshiva with the sole aim of studying Torah for its own sake. Today, now that the Kollel student “dwells in the house of G-d” for the long haul, he likewise does not learn with an eye towards finishing certain material and can continue to delve into abstract explorations as he did when in yeshiva.

In other words, whereas Rabbi Bochkovsky suggests that today’s Kollel studies are distinct from the Yeshiva world in which they used to reside, I argue that the very opposite is the case. Kollel always was, and remains, a segment of the Yeshiva. Kollel is to married men exactly what Yeshiva is to younger single men, and, broadly speaking, the learning style and expectations are more or less identical in both. Thus, in today’s Charedi community, the model beis midrash is the one familiar to us from Yeshiva, wherein one does not seek to complete a curriculum, earn a degree, and move on, but rather studies simply for the sake of engaging with the Divine Word.

Setting Study Goals

Rabbi Bochkovsky’s central thesis is that Kollel has evolved from a temporary training ground that prepared students for Torah leadership to self-contained institutions in which Torah is studied for its own sake. He argues that notwithstanding the challenges that have emerged as a result, Kollel students now occupy a more idealistic and lofty status. They pursue Torah study as a goal in and of itself, rather than merely to qualify for a leadership position.

As a result of its students’ long-term commitment, Rabbi Bochkovsky concludes, Kollel learning now reflects a desire for greater integration with daily life, a push that is expressed in a range of new learning initiatives. It is this latter point I take issue with, as I believe that quite the opposite has happened. Absence of defined learning goals has rather reinforced the conceptual similarity between Kollel and Yeshiva. Indeed, if we are looking for study outcomes that connect our Kollel men to their practical worlds, we must return to the older framework in which Kollel learning assumes clear goals and objectives.

Only by changing our conception of the Kollel and reestablishing it as a purpose-driven model will we be able to mitigate the diminishing motivation of our Kollel men. In fact, perhaps today’s Kollel students need to aim at more exalted goals than in the past. Now that Kollel’s main purpose is no longer training in preparation for a leadership position but rather learning for the sake of learning, the student should strive for complete and thorough knowledge of halacha, well beyond what might be necessary to function as a Rabbi. Thus, even if the motivation to learn is Torah study for its own sake, this should not stop us from setting goals and milestones for our learning. Rather than diluting the enterprise of Torah learning for its own sake, pursuing well-defined goals helps create pedagogic tension and drives ambition, to the benefit of the individual student, his peers, and Torah learning itself.

Programs such as Dirshu have emerged in recent years as an effort to round out the Kollel student and anchor him with fluency in Shas. While such initiatives were founded as a response to the phenomena Rabbi Bochkovsky addresses, the work is far from complete. Unfortunately, the grassroots interest in more purposeful learning structures has yet to be recognized and adopted by the Kollel system writ large.

Our call therefore must go out to the established Kollel institutions, those with the ability to influence change on a systemic level, to begin organizing a vision for goals-driven curricula and structures. These institutions are best positioned to drive significant change by modeling a Kollel student, who, while growing in Torah as the highest spiritual pursuit, is doing so in a defined and quantifiable manner with an abiding sense of purpose and dignity.

Should i continue learning Choshen Mishpat by myself off the Shulchan aruch haRav/Kitzur shulchan aruch ? or just leave it and focus on just Orach Chaim/Yoreh Deah/Even haEzer ? Since i live in a small town with no Rov and no classes or online classes i cant afford because my at home income only aids in daily needs like groceries and bills.