At the outset of this short piece on Torah and environmentalism, I wish to note a couple of preliminary assumptions that will narrow the scope of the conversation. One is that we are certainly obviated to care for the environment. Of this, there can be no doubt. The earth, after all, is God’s earth, and it deserves respect by association with its Creator. The second is that respecting the planet doesn’t mean leaving it as we find it. God Himself instructs us to develop the world, to “be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and conquer it” (Bereishis 1:25). The inherent tension between a humane custody ship on the one hand and an obligation to subdue nature on the other is sharpened by the contemporary environmentalist movement. It is this dilemma that I wish to explore in the coming lines.

My close friend Rabbi Benayahu Tabila, in his anchor article, lays out a vision for Torah society of intense activity on behalf of the environment. In his opinion, our lack of involvement in environmental issues is inexcusable. Our world is warming; its icecaps are melting, and many species are going extinct. These are serious changes. Their effect on our descendants remains mostly unknown, but scientists predict they’ll be bad. On a policy level, scientists and activists propose that we stop selfishly exploiting natural resources. It is our duty, Tavila claims, to condemn an extractive relationship with the planet that echoes the heretical approach that states, “eat and drink for tomorrow, we die” (Yeshayahu 22:13). Given that the meat industry is a central cause of deforestation and greenhouse gases, he even mentions a practical measure of calling a rabbinical ban on the consumption of meat, except for on Shabbos and festivals. In our personal lives, we look after our future, after all: “The wise man has eyes in his head” (Kohelet 2:14)—and so we ought to in our public life.

Interestingly, both his argument and mine are predicated on the virtue of humility. While he invokes humility as a reason to limit our exploitation of the world, I will emphasize the very opposite: that the environmentalist position could use a healthy dose of humility

I would like to mitigate this approach. As noted, I agree with the principle that we must take care of our planet, abiding by the Divine instruction noted by the Midrash to Adam: “Take care that you do not destroy and ruin my world” (Kohelet Rabba 7:1). Yet, the question is how much this principle must be limited and modified by other worthy principles. It is not a question of whether but of to what degree. On this, it seems that Tabila and I are not in full agreement. Interestingly, both his argument and mine are predicated on the virtue of humility. While he invokes humility as a reason to limit our exploitation of the world, I will emphasize the very opposite: that the environmentalist position could use a healthy dose of humility. Both arguments have their validity, and the true labor will be seeking the equilibrium between them.

A Time for Voluntary Celibacy?

In a recent class I taught at Hebrew University I praised Israel’s birth rates, which are the highest by far among Western democracies.[1] One student raised his hand and asked: “Why do you think this is a positive thing? Surely, fewer births would be better for the environment?” The question took me by surprise. Anti-natalism, as opposition to procreation is commonly called, is not a common Israeli position (just look at our birthrates!). It is, however, a view all too popular among environmentalists.

An extensive study published by the journal Environmental Research Letters found that the most effective way an individual can contribute to the environment is to have fewer children—far more than avoiding planes, traveling on “clean” vehicles, or becoming a vegetarian. For this and other related reasons, many young people fear having kids. An international poll showed that among 10,000 young people aged 16-25, 39% are “hesitant” to become parents. England even has an association known as BirthStrike which includes people, especially young women, who have decided against bringing children into the world because of the “severity of the environmental crisis.” Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a (somewhat radical) member of the Democratic Party, hinted that having children today might be immoral. To quote, “There is a scientific consensus that the life of our children is going to be very hard, and I think this leads young people to ask a very legitimate question—is it still OK to bring children into the world?”[2]

Views against childbirth have become more common yet they remain far from ubiquitous. Actual human behavior proves most of the world still believes it moral and proper to have kids. If this is true for the world in general, it is all the truer of Israel, whose high birthrates testify to a deep belief in the future. Among observant Jews, there would obviously be enormous resistance to the idea that we shouldn’t have children.

The world today is very well settled, a long way from the original, human-free globe. Halacha will of course not change because of this, but as a matter of principle why should we reject the idea of limiting childbirth to ensure natural resources are not exhausted? Is this not itself a moral obligation, made the more urgent by the fulfillment of our obligation to settle the earth?

But why are we so emphatic in rejecting anti-natalism? Is there no logic in limiting childbirth to maintain the world? Even at the religious level, the imperative of “be fruitful and multiply,” as well as the text-based dictum of the Sages that “[God] did not create it as emptiness, He created it for settlement” (Yeshayahu 85:18), or “In the morning sow your seed, and in the evening do not stay your hand” (Kohelet 11:6), are related to the settlement of the world and the continuation of the species. The Rambam states that their aim is to “maintain the species” (Sefer Hamitzvot 212), and the Chinuch says their purpose is that “the world should be settled, that God, Blessed Be He, desires its settlement” (Mitzvah 1). The world today is very well settled, a long way from the original, human-free globe. Halacha will of course not change because of this, but as a matter of principle why should we reject the idea of limiting childbirth to ensure natural resources are not exhausted? Is this not itself a moral obligation, made the more urgent by the fulfillment of our obligation to settle the earth?

Humility, Please

The Jews have some experience with anti-natalism. After the destruction of the Mikdash, there were groups who proposed “not to marry women and have children, so the seed of Avraham Avinu will terminate on its own” (Bava Basra 60b). The motive, in many respects, was similar to that of today’s environmentalists: it is wrong to bring children into a world in which “the wicked kingdom has spread, which decrees evil and wicked decrees upon us and abolishes Torah and Mitzvot.” The proposal was not adopted, of course, and neither was the more modest proposal of abstaining from meat and wine throughout the year. The conclusion, in the name of Rabbi Yehoshua, was that refraining from creating new life would not relieve the misery of lives currently being lived.

This is also the simple response to those who wish to limit births due to the climate threat: We continue to believe in the possibility of living well. We believe human beings are remarkable creatures who know how (or at least can know how) to deal with serious crises, as they have in the past. Moreover, we believe in God and His infinite goodness, which defines the sanctity of life itself. Those who believe in all these cannot entertain the thought that a kind of species-wide suicide, even partial, would be right and just. We must bring children to the world out of a belief in life, placing confidence in their wisdom and enterprise, and out of belief in the providence of God that “life is by His will” (Tehillim 30:6). And what of the climate threat? On the one hand, it should not be ignored; on the other, it should be addressed in a balanced manner.

Responsible people do not sit idly when confronted by a threat to their and their children’s future. Yet, alongside our sense of responsibility, a healthy dose of humility reminds us that ours is not the role of God

This balance is the product of a combination of responsibility, humility, and gratitude. Responsible people do not sit idly when confronted by a threat to their and their children’s future. Yet, alongside our sense of responsibility, a healthy dose of humility reminds us that ours is not the role of God, who sees the entire picture and decides who will multiply and who will die out. There is a certain place where we must tell ourselves, as Chazal have Yeshayahu telling Chizkiyahu, “Why do you deal with the secrets of God?” (Berachos 10a). The Sages remind us that “you are not free to desist [from the work],” yet we must also remember that “it is not upon you to finish the work” (Avos 2.16). We should recognize our limited role as part of a partnership with God: He is the true employer, while we are merely laborers.

This is also the central message of the Shemittah year that we are currently going through. Once every seven years, we leave the land in the hands of Heaven, a reminder of how our ownership of the property is really a trusteeship—the land is God’s, not ours. Our responsibility is thus deep, but its scope is limited by humility. Furthermore, it is also limited by gratitude. Our gratitude for the infinite gift of life causes us anxiety lest we sacrifice it at the finite altar of human knowledge. A person who is grateful for what he has will be wary of radical experimentation, be it social, economic, or environmental, for fear of losing the good he possesses. Again, this does not mean we should shirk responsibilities, but just the contrary: the same sense of responsibility that spurs us to act must concomitantly inspire us to caution.

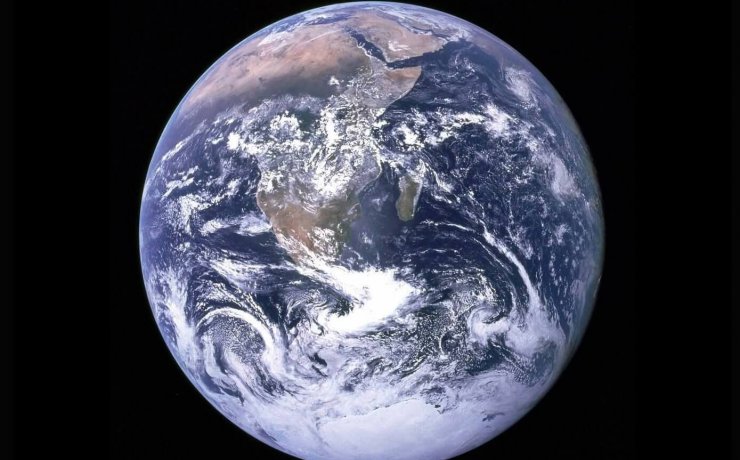

Significant parts of the environmentalist movement lack both humility and gratitude. The most common image of the movement is that of a person cradling the planet in his two palms, giving it a gentle embrace that is all warmth, compassion, and preservation. This image expresses a part of what’s good about the movement: concern for the world and its future, recognition of the effects of our own actions. But it also expresses everything that’s bad about it: condescension, excessive belief in human power over the world, and total exclusion of God from the picture.

Note the most prominent representative of the movement today: an eighteen-year-old girl named Greta Thunberg. In 2019, at the age of just 16, she was named Person of the Year by Time Magazine, and some consider her a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. At the World Economic Forum in 2019, she demanded, in the shrillest of tones, that the leaders of the world stop doing those things that jeopardize the planet’s future:

Adults keep saying: “We owe it to the young people to give them hope.” I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house is on fire. Because it is.

Thunberg’s conclusion is stark: “We must change almost everything in our current societies.” Like many members of the movement, the message is anti-capitalist, anti-Western, and largely anti-life—life as we know it, that is. All the good that Thunberg grew up with, all the achievements that enable her political activism, must be tossed aside to save the world. Later in the year, at the UN Climate Conference, she again attacked world leaders, alleging that “you have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words.” Let us remember that this is a sixteen-year-old. Perhaps some humility is in order? Some gratitude for a childhood that hundreds of millions of children would consider paradise? Thunberg, however, knows better, and warns her adult audience that they must capitulate before her arguments: “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is. […] Change is coming, whether you like it or not.”

Thunberg’s angry words emphasize the point. Prima facie, an angry sixteen-year-old lacks the basic skills, knowledge, and especially experience needed to decide complex policy questions. Crowning her as the queen of environmentalism reveals much about the movement’s character: arrogant, ungrateful, and lacking nuance.

Say “No” to Conquest

There is something counterintuitive in accusing environmentalism of arrogance. Many environmental organizations are driven by the view that the world needs to be protected from the threat of human action. These organizations operate on an ecocentric or biocentric view. They reject the view that humanity is superior to nature. Human repurposing of nature is therefore fundamentally illegitimate. Bron Taylor, who coined the term “dark green religion”—a set of quasi-religious beliefs characterized by the assumption that nature itself has fundamental and even sacred value and is therefore worthy of respect and concern—declared that an ecocentric approach “is central to solving our unprecedented environmental crisis.”[3] Ostensibly, the motivation of ecocentrism is not hubris and arrogance, but modesty in the face of creation—by contrast with the conquering spirit of anthropocentrism, which argues that humanity reigns supreme over the entire cosmos.

But refraining from conquering the earth can itself be a kind of hubris. Witness the generation of the Tower of Babel. The Torah tells us they sinned by saying, “Let us build a city and tower, with its head in the sky, and make ourselves a name lest we spread across the entire earth” (Bereishis 11:4). In the path of the Mesopotamian kings, the generation’s leaders sought to make themselves gods. At the very least, they tried to take up residence in the heavens. Rashi comments that “They sought to make war with God Himself.” However, we still need to understand the meaning of “lest we spread across the entire earth”—what did they fear, and why was this sinful?

The commandment to “be fruitful and multiply” marks a clearly anthropocentric approach, which considers humankind superior to all creation and commands us to go forth and conquer. The Babel generation feared this conquest, which would disperse them and prevent them from making a name for themselves. It was their pride and arrogance that made them deny the duty of conquest.

In his commentary on the Torah, R. Shmuel ben Meir (Rashbam) explains that their sin was avoiding the commandment God gave to Adam: “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and conquer it” (Bereishis 1:18). Humankind was created in God’s image, and as such is commanded to conquer and rule the different parts of the earth, thus stamping creation with the supremacy of the Divine image. The commandment to “be fruitful and multiply” marks a clearly anthropocentric approach, which considers humankind superior to all creation and commands us to go forth and conquer. The Babel generation feared this conquest, which would disperse them and prevent them from making a name for themselves. It was their pride and arrogance that made them deny the duty of conquest.

Arrogance is never good. It’s especially pernicious when motivating wild predictions about the future. Michel de Montaigne, the sixteenth-century essayist (he basically invented the genre), noted that “the scourge of man is his bragging about his knowledge.” Indeed, the Sages teach us to “Teach your tongue to say I do not know” (Berachos 4b). Those who fail to do so are primed for failure; when their predictions concern the future of the human race, we are all similarly primed. Science, as the case of Thomas Malthus should remind us—he warned of food shortages due to population growth, but failed to foresee the remedies that the industrial revolution would supply—does not necessarily know to credibly predict the future, especially when it comes to a subject as complicated as climate change and its effect on the planet. Indeed, the official stance of the IPCC, the international body dealing with climate science on behalf of the UN, changes continually from report to report.[4]

Arrogance drives us away from knowledge. In the environmental context, the words of Judith Curry, former head of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology and a member of the National Research Council’s Climate Research Committee, seem particularly relevant. She resigned from her position after an excellent career in climate research, explaining her decision as follows:

A deciding factor was that I no longer know what to say to students and postdocs regarding how to navigate the craziness in the field of climate science. Research and other professional activities are professionally rewarded only if they are channeled in certain directions approved by a politicized academic establishment — funding, ease of getting your papers published, getting hired in prestigious positions, appointments to prestigious committees and boards, professional recognition, etc. How young scientists are to navigate all this is beyond me, and it often becomes a battle of scientific integrity versus career suicide.

The hubris of some climate activists ultimately prevents them from studying nature disinterestedly. They know exactly what needs to be done to save the world, and whoever dares dispute them or disrupt their work is worthy of expulsion from the field—as is the case, unfortunately, in other academic spheres that suffer from over-politicization.[5] When science is supposed to undergird already-made political choices, dissenting voices will not be heard. The politicization of scientific research is, regrettably, a good reason to lower our trust in its findings.

Halacha Lema’aseh

The words “to work and preserve it” (Bereishis 2:16), which define the purpose for which Adam was placed in Eden, are interpreted by the Zohar as a reference to all the Mitzvos: “To work it—these are the positive Mitzvos, and to preserve it—these are the negative Mitzvot” (Zohar, Bereishis 27). As children, we understand that this means that Adam did not work the land, but rather engaged in Mitzvah observance: laying tefillin, wearing tzitzis, and waving the Four Species on Sukkos. A more mature understanding reverses the approach: The teaching implies that even when we observe the Mitzvos, the intent of their upkeep is “to work and preserve it”—to preserve the world, cultivate it, and repair it. The Rambam, in a similar vein, writes that Mitzvos are “the great good that the Holy One, Blessed Be He, brought to settle this world, to inherit the life of the Next World” (Yesodei Hatorah 4:13).

This labor of settling the world is true, of course, on a social level: the Torah urges us to establish a good society, predicated on charity and justice. Yet, the social aspect of settling the world has a material precondition. Conquering the world on behalf of human elevation requires us to care for the earth and forbids us from manipulating and abusing the world for our purposes, bringing it waste and destruction.

Instead of a violent and destructive puritanism, politicians and legislators would do well to learn humility and protect the environment with a determination mixed with gratitude. As believing Jews, we know that we are but partners in the great project of the cosmos. This partnership does not absolve us of deep responsibility; indeed, it should increase our sense of duty. But it allows us to execute our duties without a sense of panic and exhorts us to take concrete measures that fall short of canceling life itself

We have local and global obligations towards the environment. As Jews wishing to live a Torah-inspired life, it is important we discuss the matter and take a stand, and equally important that we recognize human responsibility towards the environment—a position that requires emphasis in our community. However, polarization on this issue in directions that stem the ebb of human life or those that are ultimately futile harms the environment itself. It causes ordinary people to think that the entire climate question is a matter of exaggerations and delusions unworthy of attention and certainly of action. Benayahu Tabila’s rabbinic proposal, whereby eating meat should be outlawed except for on Shabbos and holidays, seems to fit this category. It would cause more harm than good.

Instead of a violent and destructive puritanism, politicians and legislators would do well to learn humility and protect the environment with a determination mixed with gratitude. As believing Jews, we know that we are but partners in the great project of the cosmos. This partnership does not absolve us of deep responsibility; indeed, it should increase our sense of duty. But it allows us to execute our duties without a sense of panic and exhorts us to take concrete measures that fall short of canceling life itself.

The climate crisis discussion is important, and its appearance on the pages of Tzarich Iyun should certainly be commended. Moreover, and as I have tried to show, both sides of the climate argument raise valid points. Yet, if we are to incline to one of the two directions, it seems safer to fall on the side of “be fruitful and multiply” than on the side of Greta Thunberg.

[1] See, for instance, here: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/en/research/why-are-there-so-many-children-in-israel/.

[2] Much has been written on the relationship between having children and caring for the environment. See, for instance, the following article from BBC Science Focus: https://www.sciencefocus.com/planet-earth/human-overpopulation-can-having-fewer-children-really-make-a-difference/.

[3] Bron Taylor et. al., “Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability”, MAHB: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/statement-ecocentrism/.

[4] For a summary of the last report (AP6), and some of the changes from previous reports, see: https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-qa-the-ipccs-sixth-assessment-report-on-climate-science. For Judith Curry’s brief analysis, see here: https://judithcurry.com/2021/10/06/ipcc-ar6-breaking-the-hegemony-of-global-climate-models/#more-27876.

[5] See, for example, the following recent article in First Things on the field of political science: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2021/10/ostracizing-claremont. Naturally, in all things related to race and gender, matters are even more extreme.

Photo by Greg Rakozy on Unsplash

Shalom uvracha, R’ Pfeffer,

I am a mechanech who has also worked as a software developer with climate scientists for many years. I agree with much of what you write here, although there are a couple of points with which I would take issue.

“The hubris of some climate activists ultimately prevents them from studying nature disinterestedly… The politicization of scientific research is, regrettably, a good reason to lower our trust in its findings.”

The risk of confirmation bias inevitably arises whenever a consensus develops. It is a feature of the scientific enterprise. A lot of the time it’s not about politics at all. It’s a good reason for caution by those in the field, but it’s not a good reason for laypeople to challenge the consensus.

If you look at the amount of funding involved, politicization is working far more strongly against the scientific consensus than in support of it.

“As believing Jews, we know that we are but partners in the great project of the cosmos. This partnership does not absolve us of deep responsibility; indeed, it should increase our sense of duty. But it allows us to execute our duties without a sense of panic and exhorts us to take concrete measures that fall short of canceling life itself.”

By this logic, would it not follow that there is no place for a sense of panic under any circumstances? Even in major emergency situations, like when saving Jews in the Holocaust? Now, perhaps one could say that for a believing Jew panic is not the right emotion even then, but a sense of extreme urgency certainly would be. I’m not equating the 2 situations, but I’m just making the point that viewing ourselves as partners should not necessarily diminish the urgency with which we should view a task at hand. I do agree that from a practical perspective doomsday alarmism is usually disingenuous and counterproductive, but Greta and her ilk should not be seen as representing the severe warnings of climate science.

Yasher koach for widening the discussion on this critical issue.

Bivracha

Danny Eisenberg

Be fruitful and multiply could be pertaining to growth of vegetation not only production of children. Having for example 25 children and yet being wasteful and destructive of our planet shows a lack of gratitude to our Creator. This is not Torah. We presume far too much to our detriment. This is humility on a different level. Anything short of this, I must disagree.