Listening to certain voices in local public discourse, one sometimes encounters the claim that the coming of internet bodes the end of Haredi isolationism. The internet, such voices claim (either with fear or with hope), has broken through censorship barriers. Everything is now open. “The Charedi spring is already here,” some say. “Behind us,” they say. Like the Arab states, where government media censorship collapsed in the face of the internet, so too is the case for Charedi society.

Based on this assumption, the development of online Charedi journalism was destined to bring the blessings of a free press to Charedi society. For many years, the establishment Charedi press enjoyed a monopoly when it came to providing journalistic information to the public. This exclusivity was suddenly undermined with the introduction of Charedi news sites. The development of the online Charedi press, lacking establishment oversight and control, was ostensibly set to breach the barriers established by the same establishment press. Modernizing Charedi groups would receive appropriate media attention, and the readers would know “what is really going on” in Charedi society. But is this really what happened?

The development of the online Charedi press, lacking establishment oversight and control, was ostensibly set to breach the barriers established by the same establishment press. Modernizing Charedi groups would receive appropriate media attention, and the readers would know “what is really going on” in Charedi society. But is this really what happened?

In a study I conducted on the new online Charedi media (Charedi news sites), I sought to examine whether the online Charedi media did indeed bring a new kind of journalism to Charedi society. I investigated whether the internet, which removed censorship limits and brought about the growth of the online Charedi media, also empowered it to serve the role reserved for the press in modern democraticies. My findings show that despite the removal of official censorship, no significant change has occurred in the degree of democracy of the Haredi press. This conclusion raises an interesting question regarding the influence of internet in Charedi society in general. Perhaps the forces of social change attributed to the internet are exaggerated? Perhaps social change – for better or worse – requires more than Twitter or WhatsApp?

Perhaps the forces of social change attributed to the internet are exaggerated? Perhaps social change – for better or worse – requires more than Twitter or WhatsApp?

The conclusions of this study point to the fact that at least when it comes to a free press, more is needed than just a digital platform.

Journalism and Democracy

The press in democratic countries seves three main purposes. First, it ensures the propriety of the democratic process by airing the public voice to its political representatives on the one hand, and scrutinizing the latter to make sure they are genuinely using their power to benefit the former on the other. A robust democratic press airs the voice of its readers and serves as a mediator between them and Knesset members and other public representatives. In addition, it follows the activities of public representatives and informs the world of their activities. It thus takes care to praise those working for the public and condemns those who abuse their position.

Second, the press is a platform for public discussion, whose purpose is to ensure that those in positions of authority make the best possible decisions for all citizens. By means of the press, it is possible to conduct public debates in an open and moderate manner. A good democratic press is a platform for conducting such public discussions, so that a paper’s opinion page will publish columns in favor or against, and the public can identify with or oppose a given policy, expressing its view in a variety of ways. Via the newspaper, decisionmakers can make smarter choices. They are exposed to the range of opinions and arguments pro and con concerning matters of policy, and thus operate in a smarter and more considered manner.

Third, the press is the means of maintaining social stability, in allowing social changes to take place by means of discussion and debate, through persuasion and not by force. A good democratic press is a mouthpiece for the public. It expresses the public view and brings to the fore social ills and public criticisms and unease. It thus prevents social “explosions,” allowing for more moderate and healthy changes.

In the study I conducted, I sought to discover the degree to which the online Charedi press was serving its purpose, primarily when it comes to ensuring the propriety of the democratic process: To what degree was it mediating public opinion to political representatives or supervising the latter so that they indeed use their power to advance the public interest – and it alone. I examined this through two lenses: an online survey of readers, and interviews with journalists. The survey examined the users’ feeling of representation on Charedi websites. After receiving the data, I turned to interview four senior journalists working at Charedi news sites. During the interview, I confronted them with the findings of the survey and asked for their assistance in understanding it in depth.

The results of the survey surprised me, indicating low levels of trust among users in the online Charedi press, a sense that there is little representation, and little willingness to expose corruption or criticize politicians. One could see that among users, the level of trust in online Charedi sites was higher relative to trust in the traditional printed press. But it is likely that the users of the Kikar Hashabbat site (the most popular Charedi news site) website were a somewhat different group than those who faithfully (and exclusively) read Yated Ne’eman. The fact that they have more trust in the online press does not mean that it is necessarily more democratic. In sum, the utopian predictions that accompanied the establishment of a Charedi presence on the internet are far from coming true.

The Online Haredi Press

The online Charedi press was born without much planning. It began life in the beginning of the 2000s on several Charedi forums and blogs, freeloading on public domains. The most active forums were the Bechadrei Charedim forums at the Hyde Park site, and Haim Shaulzon blog that served evolved into a Charedi gossip column. These forums operated via the use of anonymous nicknames, and focussed mainly on events behind the scenes of the Charedi public face, often revealing a less pleasant side of Charedi public offices than presented in Yated Ne’eman reporting. Threads dealt with Charedi gossip stories, corruption scandals, and internal Haredi controversies. The anonymity and lack of oversight allowed users a free hand, and the information that flooded the forums laid no claim to objectivity or to meeting journalistic standards.

In 2004, the Hyde Park Masoret platform was established which gathered together all existing Charedi forums, and in 2005 the forum owner decided to establish the Behadrei Charedim website. Additional news sites were established at the same time, but their exposure was small compared to Behadrei. In 2009, a second Charedi news outlet was founded, Kikar Hashabbat, ultimately bypassing Behadrei.

The alternative news sites became more and more popular, and in 2009 senior rabbis in the Charedi community called for their boycott. As a result, Behadrei editors David Rotenberg and Dov Povarski resigned, and an anonymous editor was appointed in their stead. The boycott led on the one hand to the closing of the small websites which could not face the pressure, but also to the strengthening of Behadrei and Kikar. These benefited from the elimination of their smaller competitors. In 2014, former Behadrei editor David Rotenberg established a new site called Haredim 10, focusing, like its competitors, on coverage of events within Charedi society.

The variety of content at online Charedi news sites is significantly broader than the traditional press. Charedi news sites include leisure and entertainment sections, as well as criminal reports of cases of violence and sexual assault – reports that would not appear in the written press. The sites do not refrain from publishing (modest) pictures of women, and the contents of the women’s sections do not always fit the image of the Charedi woman as presented in the traditional press.

The establishment Charedi press which set the agenda for many years on the Charedi street found itself competing with online news sites. Until their formation, the Charedi dailies had an almost complete monopoly on the flow of new information into the Charedi community and from it. […] These made no pretense of providing objective information. To the contrary, as the editor of Hamodia once said candidly: “We believe in the right of the public not to know…”

The manner in which the online Charedi press was formed created a sense that Charedi society was on the verge of a revolution. There were reasons to think that the entry of Charedi websites into the arena would change the balance of political and social power. The establishment Charedi press which set the agenda for many years on the Charedi street found itself competing with online news sites. Until their formation, the Charedi dailies had an almost complete monopoly on the flow of new information into the Charedi community and from it. While there were already weeklies that were not as strictly supervised by rabbinic authority, these usually fell in line with the partisan press, and in order to get up to speed current affairs in Charedi society one needed to subscribe to one of the party publications. These made no pretense of providing objective information. To the contrary, as the editor of Hamodia once said candidly: “We believe in the right of the public not to know…”

We would thus expect the Charedi news sites to become the democratic mouthpiece of Charedi society. But reality has shown that this prediction is far from full realization. Below I will lay out the results of the survey I conducted, following which I will present highlights from interviews with journalists on the subject.

Study Results: Whom do the Haredi sites serve?

225 Charedim with regular internet access answered my survey. Some 56% of them were men and 46% of them women. In the survey I sought first of all to confirm that participants genuinely consume news on a regular basis by means of Charedi news sites. Following this, I presented the core questions which dealt with their sense of representation in the online Charedi press, as well as the matter of readiness to expose corruption and criticize Charedi politicians in the online Charedi press.

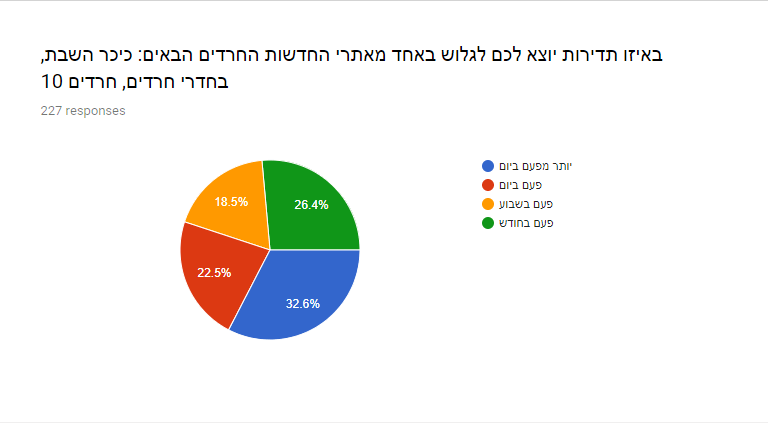

As can be seen from the findings in the following graph, the online Charedi press is a news source of significant weight.

Among participants in the survey, over 55% of users at the Haredi news sites visited at least once a day. This data supports what we know about the sites’ enormous popularity in recent years. According to the report of traffic data analysis firm SimilarWeb, Kikar HaShabbat has some 1,920,000 visits a month, Behadrei has 1,740,000, and Charedim 10 has close to half a million. These are very high numbers. If we take into account the filters that many Charedi families install on their computers, which deny them access to non-Charedi news sites, we find a near-exclusivity for Charedi sites in providing news and setting the agenda for a significant portion of the Charedi population.

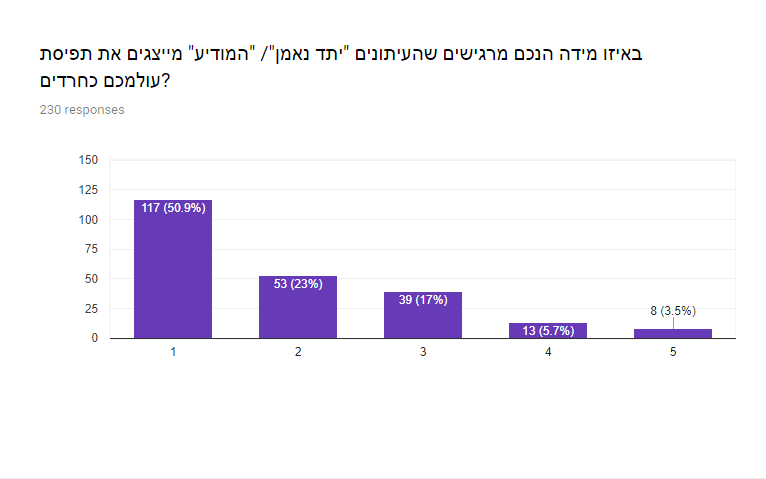

Concerning the degree of trust of survey participants in traditional Charedi media, it turns out that more than 75% of respondents (based on a rising scale of 1 to 5) feel that it does not represent their Haredi worldview.

The reason this data point is critical is that if journalistic alternatives did not emerge in the form of Charedi news sites, most of the sample group would ostensibly not be appropriately represented.

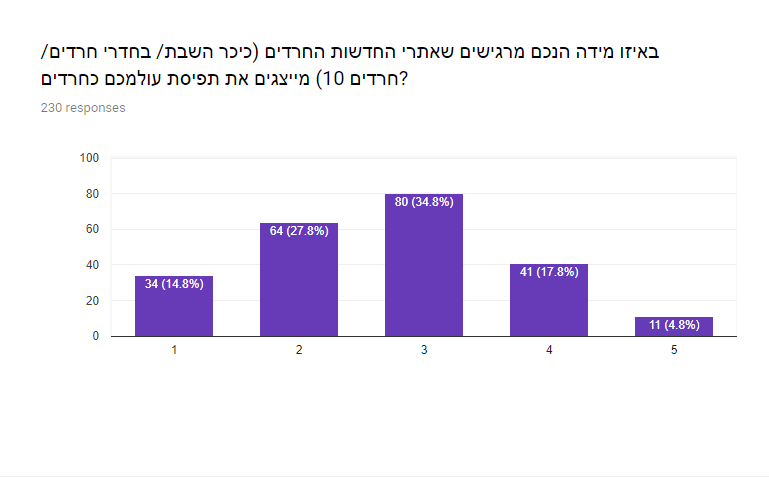

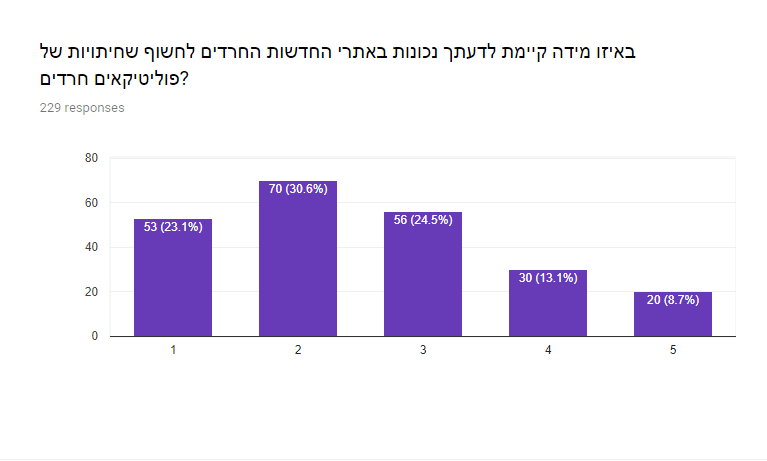

But do those asked feel that the Charedi news sites represent their worldview instead? Here are the surprising results:

Certainly, distribution of those who feel represented and those who don’t is somewhat improved, but only some 20% responded that the Charedi news sites represent their worldviews. 80% of respondents were still on the scale between a fair degree of representation to none at all. This means that while feel that there has been an improvement in their sense of being represented by the press, they remain far from being satisfied from their degree of representation. Imagine how this lack of representation affects the Charedi political and social agenda. Assuming that Haredi public representatives indeed seek to advance their constituents’ interest, how will those representatives know what the Charedi public interest is if it does not receive a voice in the press?

To the question “To what extent do you believe there is readiness on the part of Charedi websites to expose the corruption of Charedi politicians?” 54% of respondents said that there is no such readiness. If we add to this the 24% who said that there is a fair degree of readiness to do so, this still amounts to a very low level of trust.

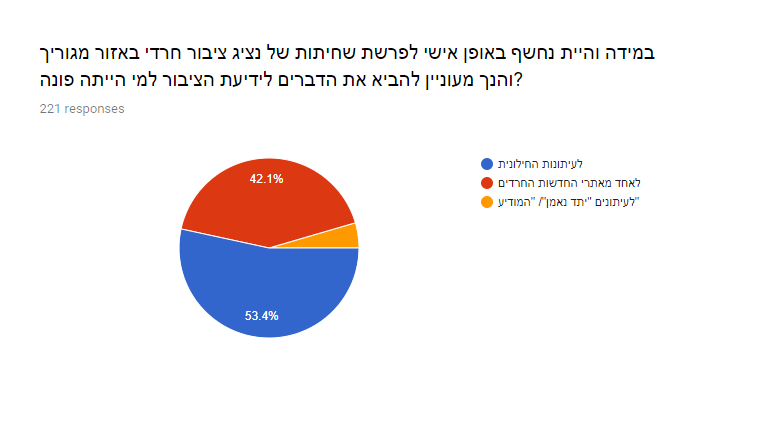

Moreover, when asked which media body they would turn to if corruption was exposed on the part of a Charedi representative in their place of residence, 53% said that they would turn to the secular press. This means that large percentages of readers of the online press still feel that it will look the other way and not expose the misdeeds of public representatives.

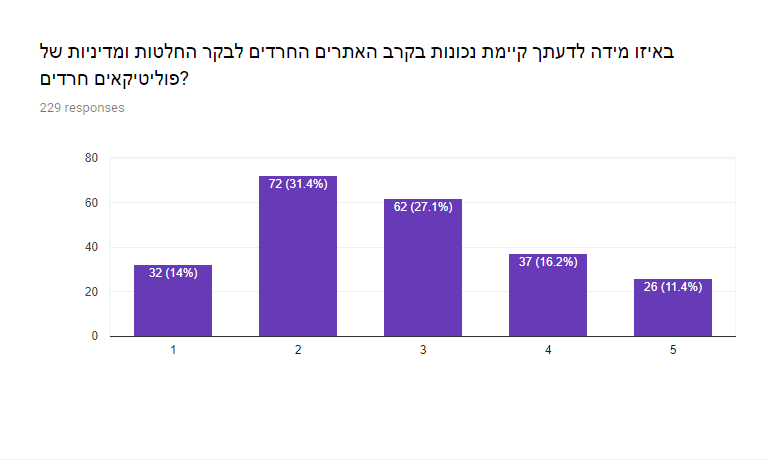

Similar data emerged when respondents were questions as to the readiness of the online Charedi press to criticize Charedi politicians. One can see a greater readiness to criticize politicians as opposed to exposing corruption, but this is still only middling readiness at best. Some 25% felt that there is a readiness to criticize decisions and policies of Charedi politicians. This data point is important: A quarter of respondents felt that politicians cannot make decisions and determine policy at will without suffering public critique. However, high percentages still feel that there is no readiness in the Charedi online press to criticize politicians, and that the online Charedi press is not the ideal way to apply public pressure on said politicians to change direction.

Democratic Journalism?

This data paints a fairly grim portrait when it comes to the role of the online Charedi press as a free press. This is indicated by the fair to low sense of users’ representation, the unreadiness to expose corruption or criticize the politicians, and by a strong sense that the general press is needed to expose corruption on the part of sectorial representatives. Those who thought that the Charedi online press would bring the spirit of the free press to the Charedi community will likely be disappointed by these numbers.

The result presents an interesting dynamic – a lack of interest on the part of the online Charedi press to expose corruption leads to such exposure usually being done by the general Israeli press. The result is the strengthening of the Charedi community’s sense of persecution, as though these reports are driven by hatred of Charedim.

I do not claim that the general press’ hands are entirely clean; to the contrary, the coverage of Charedim in the general press is often slanted, unfair, and quick to damn. Still, the data points to the failure of the online Charedi press to do its job, and this has significant consequences when it comes to proper public administration and the fair distribution of public goods.

The fact that “modern Charedim” feel represented, even if partially, adds an important voice to the Charedi discourse. But the unreadiness to expose corruption and the fact that most respondents said they would still prefer to go to the general press in cases of political corruption, indicate that there is still a long way to go when it comes to creating a truly free press for Charedi society

We cannot ignore that the sense of representation among Charedi individuals consuming the online Charedi press has improved relative to the era when Yated Ne’eman and Hamodia were the sole media outlets of Charedi society. The fact that “modern Charedim” feel represented, even if partially, adds an important voice to the Charedi discourse. But the unreadiness to expose corruption and the fact that most respondents said they would still prefer to go to the general press in cases of political corruption, indicate that there is still a long way to go when it comes to creating a truly free press for Charedi society.

Establishment Status and a Sense of Patriotism

In order to properly understand the results of the survey, I interviewed four senior journalists working at online Charedi outlets, and asked for their reaction. I shared the data with them and asked them to help me understand it better. The journalists, unlike me, were unsurprised at the data and provided explanations based on a knowledge of the nitty gritty of online Charedi journalism. During the interviews it transpired that journalists working for news sites would love to expose public corruption just like their colleagues at non-Haredi news sites, if only for purposes of ratings. But in practice, the online Charedi press usually refrains from exposing corruption for two reasons: economic and ideological.

The first noted reason was economic considerations. One consideration is the high cost of conducting investigative pieces. Only media corporations, they claimed, have the necessary resources to carry out quality journalistic investigations. In addition, the Second Media Authority oversees them and demands they provide the goods in exchange for a franchise of quality content, which includes investigative pieces. News sites, by contrast, are subject to no such oversight, and their financial resources are marginal compared to corporations. Media corporations employ hundreds of workers, while Charedi news sites are usually operated by a small staff of some ten employees (journalists, editors, graphics department, marketing).

However, journalists claimed that there is another form of economic constraint: the pressure applied to Charedi sites by advertisers. Contrary to the normal meaning of that term, these are usually not commercial advertisers but rather government and municipal bodies. The pressure is applied on the media bodies as follows: The press is economically dependent on the ad companies. The ad companies are among other things dependent on the ad budgets of municipalities and government bodies. And government bodies can react negatively to bad press.

Take a local paper, for instance. If it publishes critical coverage of the mayor, it risks its relations with the ad company representing the municipality. In addition, municipalities and local councils obligated by law to publish statements to the public can avoid doing so at critical outlets. These ad budgets are often the lifeline of local papers. Just like local papers, Charedi news sites have over time developed an economic dependency on municipalities and government bodies, which shapes to a large degree the manner in which public representatives are covered. Beyond this, advertisers fear boycotts resulting from their cooperation with parties hostile to rabbic figures and authority. Though as they grow in strength, such constraints will less, these financial considerations nonetheless moderate the operators of Charedi news outlets.

The second group of reasons preventing Charedi outlets from doing their job in covering and critiquing is ideological. For reasons of loyalty to the positive image of Charedi society, which I would call a “sense of sectorial patriotism,” and based on a desire to fall in line with the accepted norms of the establishment press – as indeed the non-partisan weeklies did – Charedi journalists avoid representing critical positions or exposing improper behavior on the part of Charedi public representatives.

The online Charedi press consideres itself obligated to erect a solid wall of defense, presenting Charedi society in a positive light, and presenting those who criticize it as haters of religion. This, even in cases where the position of the online Charedi press does not align with the conservative approach of the establishment

The sense of communal loyalty, alonsdie a desire to not be seen as traitors (a fifth column on their home base) or as granting legitimacy to external attacks against Charedi society, makes them close ranks with the establishment Charedi press. This tendency is especially felt whenever Charedi society is attacked by the general media or by politicians from outside the community. The online Charedi press considers itself duty-bound to erect a solid wall of defense, presenting Charedi society in a positive light and those who criticize it as haters of religion. This applies even in cases where the position of the online Charedi press does not align with the conservative approach of the establishment.

This sentiment derives from a deep sectorial commitment to maintain a united front against the non-Haredi public. It leads all Charedi journalists to react against threats from the outside and unite ranks around the foundations of the Charedi society. Thus, even when journalists criticize Charedi society, they often do so in a way that does not play into the hands of outside critics.

Alongside this tendency, the desire of the Charedi online press to compete with and even replace the establishment Haredi press leads it to adopt its competitors’ style. Thus, paradoxically and fascinatingly, the more the internet penetrates the Charedi mainstream, the more conservative the online press becomes

Alongside this tendency, the desire of the Charedi online press to compete with and even replace the establishment Haredi press leads it to adopt its competitors’ style. Thus, paradoxically and fascinatingly, the more the internet penetrates the Charedi mainstream, the more conservative the online press becomes. In other words, the more the number of Charedim connected to the net increases, the greater the relevance of the Charedi sites, and the more they become sought after by politicians and rabbis. The hope of Charedi sites is that as Charedim continue to tread toward an ever-greater online presence, they will become the central media outlets and gain exclusivity in providing news reporting. Their fierce desire to remain a “Charedi press” leads them to take conservative Charedi stances and avoid provocations. Moreover, the online Charedi press enjoys accusations of excessive conservatism, as this assures its place within the Charedi mainstream.

The dual pressures of striving to becoming part of the establishment and the lingering sense of patriotism derive from different sources. The former derives from an internal source within Charedi society, while the latter is sourced in non-Haredi Israeli society. But these two pressures together create a pincer movement working on the online Charedi press that largely shapes its character and function.

The online Charedi press will therefore refrain from taking a strident position that contradicts the stance of the Charedi leadership or the community’s political representatives. At best, it will point to a lack of coherence in decisionmaking. Its sharpest critiques will be that its representatives are not faithful to their own declared values. This criticism will always make use of claims made by the conservative press, based on a demand that they adhere to the positions of the Charedi population at large.

This striving for establishment status also harms representation, since it pushes the online Charedi press represent the prototype of the “ultimate Charedi” – a fairly theoretical figure, who in any event is not common among their readers. In addition, it leads the online Charedi press to abandon the critical spirit from which it grew and encourages it to adopt the style of the press it aims to replace. Moreover, the sense of patriotism embedded deep in the online Charedi press also harms its desire to expose corruption, so as not to be seen as a fifth column by the public. Even when Charedi journalists feel that criticism of a Charedi representative is justified, they do not reveal this to the public, so as not to weaken the political representatives on the front.

Without understanding these to factors, one cannot understand how the online Charedi press operates.

***

Combining the survey data with the findings of the interviews, we are presented with a complex picture when it comes to the role of the online Charedi press. Clearly, it does not function quite as the free press does in representing the public and in exposing public corruption. This is an important point, since this lack of functioning significantly affects the conduct of Charedi public representatives. If Charedi news sites do not represent the worldview of its users, then it is likely that political representatives will not feel the public pressure to represent them. Furthermore, if Charedi news sites are unwilling to expose corruption and criticize politicians, then it is likely that there remains much room for moving toward good government and a fair distribution of public resources.

If Charedi news sites do not represent the worldview of its users, then it is likely that political representatives will not feel the public pressure to represent them. Furthermore, if Charedi news sites are unwilling to expose corruption and criticize politicians, then it is likely that there remains much room for moving toward good government and a fair distribution of public resources

However, it is not clear that the time is ripe for a free Charedi press; it might be that the Charedi public itself is unready for it. If journalists feel that exposing the corruption of a Charedi representative will make them be seen as a fifth column by users, then it is not the press that needs to become more democratic, but rather the consumers themselves. Concomitantly, if the media pressure directed by the general press toward the Charedi public continues to be aggressive, slanted, and unfair, then the online Charedi press will lack the public legitimacy to operate properly. Either way, the path to a free press remains a long one, and it appears that the prediction that the internet would bring about a fundamental change in Charedi society has some time to reach its full realization.