Rav Chaim Kanievsky zt”l, fondly known to all as R’ Chaim, was not an ordinary “Gadol”—the standard term used in reference to rabbinic luminaries of the Charedi-Lithuanian sector. He was not a Rosh Yeshiva, held no rabbinic position of any type, seldom gave shiurim, had no disciples to speak of, and ensured that people around him knew that “I am not a Rav.” When somebody once referred to him as Maran (“our great rabbi”) in his presence, he instantly corrected “Chamoran”—combining the honorific with the word “chamor,” an ass. This is all quite outside the pale of the “Gedolim handbook.”

Also unlike so many of the past Gedolim—the Chazon Ish, R’ Chaim’s father the Steipler, Rav Shach, Rav Elyashiv, and so on—he was entirely unfamiliar with the ways of the world. This was certainly true politically; the story (unverified) is told that many years after his death, R’ Chaim inquired whether Ben Gurion was still Israel’s prime minister. But it was true on the basic physical level, too. On the day of his funeral, one of his grandsons noted that when he was offered some chocolate to mitigate the bitter-mouth symptoms of dysgeusia, he inquired as to how one eats it. The fact that R’ Chaim, then in his early nineties, was unaware as to how chocolate is consumed, joins countless vignettes indicating his detachment from the experiences we define as everyday life. Some, such as the time when he asked the driver next to him (back in the days of manual gearboxes) if he can help with stirring the gasoline, are presumably tongue in cheek—but they don’t make them up about anybody else.

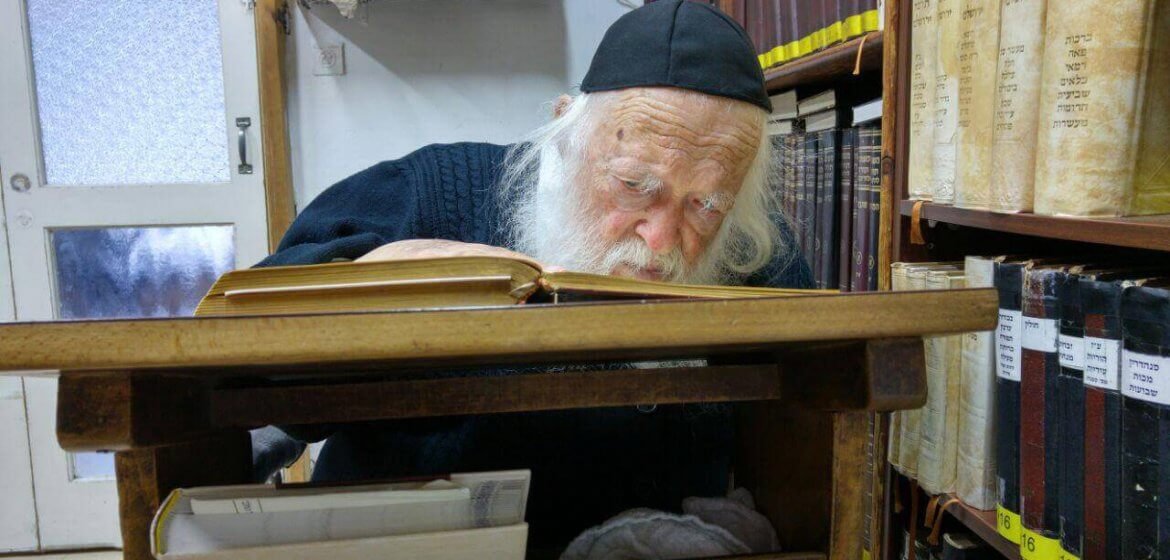

R’ Chaim was Kulo Torah. He really had nothing in his world but Torah—both its study and its fulfillment, but mainly its study. A nephew recounted how every R’ Chaim memory he recalls found him in the same position, bent over a Torah volume—learning at the top of his staircase at home; learning while sitting on a bench at the back of Kollel Chazon Ish; davening his short shemoneh esrei (three minutes or so) and immediately returning to his learning.

The same nephew described a typical Friday night meal at the Kanievsky’s. R’ Chaim would sit at the head of the table, a lectern (shtender) by his side. He would make Kiddush with his head almost buried in a sefer, and would continue learning while everybody washed their hands. Then he would get up to wash, return to the table, and continue learning even as he sliced the Challah. After five minutes, he would ask the Rebbetzin if they could bench. She would answer that they still needed to serve the fish, at which his eyes would bounce back to his sefer. The Rebbetzin would serve the fish, R’ Chaim would eat a little and return again to his study, and within five minutes he would ask again: “Are we ready to bench?” But this would still be before the soup. He would return again to his sefer, and so the meal proceeded from course to course, folio to folio.

R’ Chaim personifies the difference between the beautiful and the sublime: beauty is a part of our world, and we can aspire to it, while the sublime is outside of our everyday experience and we can barely touch it

R’ Chaim’s knowledge of Torah was also sui generis. The word encyclopedic barely does it justice. It was total mastery. One small example, one of hundreds or thousands, provides an illustration. Somebody once asked R’ Chaim if there is any Torah source for the karma-oriented idea that if a person honors his parents, he, too, will be honored by his children. R’ Chaim responded on the spot with a wondrous palindrome in the words “vayavei le’aviv,” describing Esau’s act of honoring his father Yitzchak. The fact that the words can be read from both directions indicates that the honor of one’s parents is returned by one’s children. R’ Chaim’s command of primary Torah texts and his mental agility within them was unparalleled, probably for several generations.

All of this is, of course, quite atypical even of great rabbinic leaders, which begs the question: What is the legacy of R’ Chaim? What does he leave behind? Can he be a role model for us and for our children? How are we to relate to this unique phenomenon? In the following short words, I wish to suggest that R’ Chaim personifies the difference between the beautiful and the sublime: beauty is a part of our world, and we can aspire to it, while the sublime is outside of our everyday experience and we can barely touch it. As such, R’ Chaim is not a classic role model for us and our children. Rather, he embodies the rare greatness that continues, by the grace of Hashem, to be part of the Jewish People. Our world is all the richer for it.

The Legacy of B’nei Aliyah

Understanding the persona of R’ Chaim’s begins with the well-known dispute between Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and Rabbi Yishmael on the question of the balance between the Torah study and involvement in “the ways of the world”—derech eretz. According to Rabbi Yishmael, the righteous path of Torah study is “to balance [Torah study] with the ways of the world”—to combine Torah with regular human conduct, most prominently the duty to engage in productive labor. Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai disputed this, stating that one must invest the entirety of one’s human resources in Torah study, and rely on Divine providence for everything else: “When Israel does the will of God, their work is done by others.” The debate was decided, centuries later, by the Talmudic Sage Abaye: “Many did as Rabbi Yishmael instructed and succeeded; as Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai instructed and did not succeed” (Berachos 35a).

For the great majority of people, the way of Rabbi Yishmael is the correct path to take. Indeed, the Sages consider deviation from the boundaries of derech eretz to be a tangible danger. It is “the toil of both” (Torah combined with labor) that “makes one refrain from sin” (see Rema, Orach Chaim 246:21).

As Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin said, Abaye’s instruction speaks to the many, the multitudes for whom “it is virtually impossible to engage themselves all their days in Torah study alone, and not devote even one moment for the sake of earning their sustenance” (Nefesh Hachaim 1:8). I would add that although today we live in an era when the number of Torah students has grown exponentially, the vast majority remain in the ilk of Rabbi Yishmael. They are aware of and care about what they will eat for lunch, they worry about the state of their bank account, and they even invest thought in where to take their summer family vacation. Their study, while in the framework of a “full-time” Torah occupation, remains within the boundaries of derech eretz.

Unique individuals, on the other hand, can take the path of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai—in a similar vein as the zealotry of Pinchas, which also departs, though in a different sense, from the regular order of the world. Such individuals—they can only remain individuals, for no society can function based on the Bar Yochai model—serve as a lighthouse for others. They remain detached from all things practical, and their leadership is thus anomalous—but this is their greatness. Their livelihood, as Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai promised, is secured “by others.”

The legacy of R’ Chaim is the legacy of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. It is the legacy of those unique individuals for whom there is nothing in the world other than Torah, for whom there is no need and no desire to depart from the shtender, and even their occasional departure is ostensible alone

The legacy of R’ Chaim is the legacy of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. It is the legacy of those unique individuals for whom there is nothing in the world other than Torah, for whom there is no need and no desire to depart from the shtender, and even their occasional departure is ostensible alone. It remains with them always. It is the legacy of faith that Hashem will never leave the Jewish People without those unique people—individuals such as the Vilna Gaon, the Chazon Ish, and now R’ Chaim, without meaning to compare and contrast them—whose Torah study is able to transcend all else and whose immersion in Torah study leaves room for nothing besides.

“I have seen elevated people [b’nei aliyah],” said Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai elsewhere, “yet they are but few” (Sukkah 45b). They are few by definition, yet they are forever present among the Jewish People. R’ Chaim was such a ben aliyah, perhaps in the mold of the “Chassidim Rishonim”—those who spent an hour in preparation for each prayer and an hour in internalizing it. That, itself, is his legacy.

A Man of the Attic

My father-in-law, Rabbi Reuven Leuchter, explains that the tern b’nei aliyah should be understood not only in its idiomatic sense—“elevated people”—but even in the literal sense of an attic: “attic people.” The Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s of the world, those who live the elevation that immersion in Torah can bring, have more than one “floor” to their personas. They possess, within their own psyches, an attic—a higher plane, beyond that of ordinary people, on which they live.

R’ Chaim’s Torah was reflected in his Kedusha—his holiness. He simply lived on a different level than the rest of us. While he was studying some of the more esoteric laws of Kashrut—the ones generally skipped over by everybody else, which R’ Chaim always made a point to study—a cricket flew through his window and allowed itself to be inspected for purposes of study (the story, in a rare twist, was confirmed by R’ Chaim himself).[1] Many visitors have testified to R’ Chaim’s knowing their story and relating to it even before they told it.[2] Many have related salvations beyond the order of nature that occurred in the wake of R’ Chaim’s blessings.[3] Irrespective of what we make of these anecdotes, they reflect R’ Chaim’s unique stature.

Indeed, the study of the Torah at this kind of level brings a person special elevation. “Nefesh Hachaim,” a work often seen as foundational to the Lithuanian yeshiva system, expounds at lengths on the elevating effect of Torah study, but the basic premise is found in Pirkei Avos:

Rabbi Meir said: Whoever occupies himself with the Torah for its own sake, merits many things; not only that, but he is worth the whole world. He is called a beloved friend; one that loves God; one that loves humankind; one that gladdens God; one that gladdens humankind. And the Torah clothes him in humility and reverence, and equips him to be righteous, pious, upright, and trustworthy; it keeps him far from sin, and brings him near to merit. And people benefit from his counsel, sound knowledge, understanding, and strength, as it is said, “Counsel is mine and sound wisdom; I am understanding, strength is mine” (Proverbs 8:14). And it bestows upon him royalty, dominion, and acuteness in judgment. To him are revealed the secrets of the Torah, and he is made as an ever-flowing spring, and like a stream that never ceases. And he becomes modest, long-suffering, and forgiving of insult. And it magnifies him and exalts him over everything (Avos 6:1).

One reads the Mishnah, in all its details and qualities, and one sees R’ Chaim. Notably, while lauding the elevated status of Torah scholars, the quotation does not paint a picture of aloofness and estrangement, but of an elevation that is accessible and close. This certainly embodied R’ Chaim, who was anything but aloof and inaccessible.

The same above-mentioned nephew—Shmuel Greiniman, an acquaintance and a sound source of anecdotes—was with his brother in R’ Chaim’s home during visiting hours when a lanky Breslov Chassid, clearly new to religious observance, walked in. “Rebbi, I have a problem,” he opened, “I am cold the whole time. What shall I do?” “Wear a warm coat,” answered R’ Chaim. “But I already have one,” said the visitor, beckoning R’ Chaim to feel his coat, “and it doesn’t help.” R’ Chaim felt the coat and asked: “Where do you live?” “In Safed.” “Safed is cold. Move to Bnei Brak, where it’s warm.” An awkward silence. “But my wife works in Tiberias. Should we move there?” R’ Chaim chuckled and replied: “Tiberias is close to Safed, and is also cold. Come here where it’s warm.” The Chassid kissed R’ Chaim’s hand and left the room.

R’ Chaim allocated his most precious resource—time—to multitudes who send him questions, sought his counsel and blessing, or just paid a visit. He was an “attic person,” elevated beyond everybody else. But the attic was somehow accessible

At this point, one of the nephews turned to R’ Chaim in amazement and asked the obvious question: “How do you manage to handle all of these questions?” “What can I do,” answered R’ Chaim. “The Mishnah tells us that one must receive every person with a pleasant countenance.” R’ Chaim was elevated, he was in a certain sense otherworldly, but he remained pleasant. Always. He had a sharp and warm sense of humor. And he cared, deeply, for every Jew. He used to complain that people came to him when they had troubles, but didn’t return to him when things got better.

R’ Chaim allocated his most precious resource—time—to multitudes who send him questions, sought his counsel and blessing, or just paid a visit. He was an “attic person,” elevated beyond everybody else. But the attic was somehow accessible.

Of Beauty and Sublimity

Philosophers, notably the statesman Edmund Burke,[4] have reflected on the difference between the beautiful and the sublime. Beauty inheres in the everyday elements of life whose striking appearance brings us joy: a superb painting, a magnificent composition, or a remarkably cute child. These inspire within us a sense of pleasure, delight, or gratification. By contrast, sublimity is present in elements that are outside of our everyday life, mysteries that are somehow beyond. This can be said of the vastness of the sea, the infinity of the heavens, the majesty of the stars, or the power of a tornado. In their highest degree, these phenomena inspire awe; in lesser degrees, they awaken admiration, reverence, and deep respect.

Neither category, it is important to note, includes the other. The beautiful is not sublime, and the sublime is not beautiful. They are separate categories, each with its own distinct character, each inspiring within us a different set of feelings and emotions.

There is much Torah in the world that is beautiful. There is much that brings us pleasure, much that bequeaths us wisdom. But the totality of R’ Chaim’s Torah—totality in its manner of study and totality in terms of unprecedented knowledge, even in terms of past generations—was sublime

There is much Torah in the world that is beautiful. There is much that brings us pleasure, much that bequeaths us wisdom. But the totality of R’ Chaim’s Torah—totality in its manner of study and totality in terms of unprecedented knowledge, even in terms of past generations—was sublime. It was not what we would generally call beautiful; it was not the kind of leadership that we generally admire; it was sometimes hard to understand. But it was vast, immense, infinite, awesome. It was sublime.

And people got it—not just the Lithuanian part of the Haredi sector, but people from far and wide. In a truly unprecedented move, the Israeli daily Yediot Acharonot, a newspaper that represents the face of Israel, published the picture of R’ Chaim on its front page with the caption: “The Gedol Hador is gone.” To see the words “Gedol Hador” in a secular newspaper is news indeed. His passing was marked on the football pitches alongside the synagogues. All appreciated that there was something special here, something unique that is no longer.

R’ Chaim’s legacy is R’ Chaim—it is the very fact that such individuals still walk among us, looking down from their “attic” and shining down to our world with their Torah. They are few by definition. R’ Chaim, both in the way he lived and in the scope of his Torah, is not a phenomenon that we can aspire to emulate. But his very presence inspires us with hope and with faith, with an awareness of the greatness of Torah, and with a consciousness that Hashem continues to dwell among the Jewish People.

[1] For Rabbi Dan Tiomkin’s presentation on this matter, see here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyJmo2o38lU [Hebrew].

[2] For one example, see here: https://vinnews.com/2022/03/21/baruch-ben-yigal-father-of-fallen-soldier-tells-of-amazing-meeting-with-rav-chaim-kanievski/.

[3] For one example, see here: https://www.kikar.co.il/415266.html.

[4] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757).

Picture by Shneur Zalman, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

His piety and sublime nature often leads many to underappreciate his enormous scholarship in talmudic literature, as attested to in a letter recommending RCK ztl for the Israel prize in Talmud over 50 years ago by his cousin the GRASH ztl. His mastery of Torah was obvious even over half a century ago. Comparable individuals rarely exist.

Thanks very much. One of the best eulogies of Rav Kanievsky that I’ve read.

I appreciated the setting aside of R’ Chaim from other Gedolim (which wasn’t done by most maspidim). He really was sui generis.

The question is in which way does the detachment of R’ Chaim fit with any kind of leadership model, or even any model at all. Clearly, you can’t be a “leader” if you’re not deeply attached to the surrounding, so I gather the article is claiming that he wasn’t a “leader,” though he might have been manipulated etc. But even without being a leader, we Jews don’t have a “monastery model,” so how does R’ Chaim fit in? Perhaps, as the article notes, this is a “Nefesh Hachaim” model, but it remains somewhat unclear.