One of the hottest items on Israeli media in recent weeks is the economic impact of Charedi society—today and, more crucially, tomorrow. The fact that over 50% of Charedi men (between ages 25-65) are not at work (at least, not on the books) is already a major drain on Israel’s economy, and it is set to become an ever-growing drain as Charedi children—one in four of every Israeli first-grader studies in the Charedi school system—grow to be adults. For non-Charedi Israel, the issue is becoming a real concern, currently exacerbated by the new incoming government whose plans include weakening the financial incentives of leaving Kollel (full-time Torah study) for work.

In Charedi media outlets, this issue is understandably underplayed; the only mention comes in the accusatory context of labeling the secular media as anti-Charedi or antisemitic. But this approach does us a disservice. Charedim are dependent on the success of Israel’s economy no less than any other sector. We all need the same MRI machines, we all need a strong military to defend us against our (many) enemies, and we all want the state to continue its impressive support of Torah study alongside robust welfare contributions. We ought to be thinking about our place in Israel’s economy rather than evading the issue with accusations, justified or otherwise, of anti-Charedi sentiments.

In the present article, I will try to fill the void with an internal presentation of Charedim and the economy. The findings, based on research conducted in Israel and around the world,[1] are a call to action for anyone who cares about both Charedi society and Israel broadly. They urge us to come up with clear and concrete answers concerning our plans for the future. Certainly, we should avoid empty and provocative statements, such as MK Goldknopf’s (bizarre) condemnation of Israel’s economy over the past 70 years and his promise of “Let the Charedim run the country and see what happens.”[2] We need to do better than that.

Even if we support the current situation in which a high proportion of Charedi men opt out of the workforce—a choice that many make and whose morality, on a social level, deserves internal scrutiny—it is still important to be aware of the nature and magnitude of the cost. It is too easy to say, “We have more meaningful things in life than think about economic growth.” It is harder to say that we will forgo urgent medical care for our loved ones or crucial defense systems to protect our homes from missile attacks.

Unlike much of the secular media, my starting position is one of deep appreciation for Torah study and its tremendous value. We need to do everything we can to save Yavneh and its Sages, to quote the famous demand made by R. Yochanan b. Zakai

Unlike much of the secular media, my starting position is one of deep appreciation for Torah study and its tremendous value. We need to do everything we can to save Yavneh and its Sages, to quote the famous demand made by R. Yochanan b. Zakai. Yet, we also know that “if there is no flour, there is no Torah,” and our Yeshiva world certainly needs a strong economy to ensure its stability and sustainability.

Some of the data I will present below were gleaned from a conference held by the business newspaper “TheMarker” in collaboration with the Charedi financial website “Business,” which specialized in the Charedi contribution to the labor market. The keynote speech delivered by Bank of Israel Governor Amir Yaron highlighted two ways to depict the influence of the Charedim on the economy. The first, popular for politicians looking to win votes, refers to the significant element of Charedi society that opts out of the workforce. The second is to identify the barriers to this contribution and explain the benefits of achieving their full potential.[3]

In this spirit, I believe that a balanced representation of the country’s economic future can contribute to the discussion far more than an emotional argument about how much Charedim contribute to general society.

Doing the Math

At the calculation stage, it seems prudent to allow the numbers to speak for themselves. Later, I will present some predictions based on data collected over the past decades.

Beginning with demographic data, the number of Charedim in the State of Israel in 2021 was 1.23 million out of approximately 9.5 million citizens.[4] This reaches 13% of the total population or 16.5% of the number of Jews in the country. By comparison, in 2009, the number of Charedim was 750,000, approximately 10% of State residents. Over the last few years, the natural growth rate of the Charedi population has been 4.2% per year, compared with 1.9% for the overall population of Israel or 1.4% for the general Jewish population.[5] If these growth trends continue, the Charedi population will double its size every 16 years. By comparison, the Israeli population as a whole is expected to double its size every 37 years and the non-Charedi Jewish population every 50 years—though recent trends should show a gradual closing of the gap (between the Jewish and non-Jewish populations).[6]

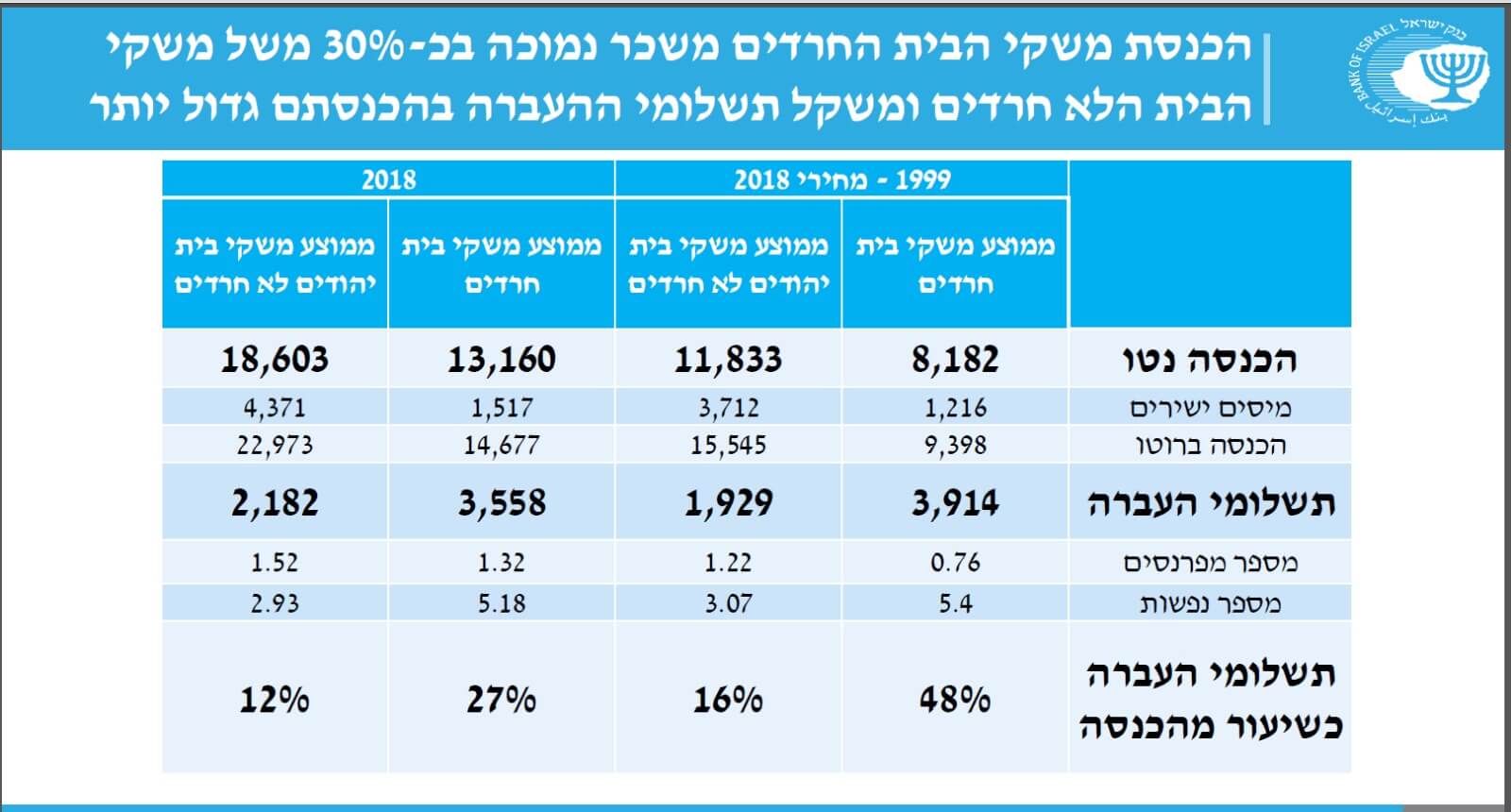

At the conference mentioned above, the Governor of the Bank of Israel presented the following data: A non-Charedi Jewish household pays an average of 4,371 ILS in direct taxes per month, compared to 1,517 ILS paid by a Charedi household and 1,587 ILS by an Arab household. Based on expected population growth, if in 2018 the Charedim were 7% of all households in Israel,[7] by 2065—a prediction imprecise but still valuable—they will reach a full 23% of households. The Bank of Israel found that if the proportion of Charedi households today were the same as expected in 2065, a 16% increase in direct taxes would be required for the state budget to retain its current level.

The cost of an increase in the Charedi population, assuming the rate of their economic contribution will not change, includes not only a decline in revenues to the state treasury due to lower direct and indirect taxes but also a heightened expenditure on government transfer payments such as benefits of various kinds. According to the Bank of Israel, the net income of a non-Charedi Jewish household in 2018 averaged 18,603 ILS per month, 2,182 ILS of which were transfer payments. In contrast, among Charedim, the average monthly income was 13,160 ILS per month, of which 3,558 ILS wire transfer payments.[8]

The encouraging part is that the situation is far better than it was two decades ago when transfer payments made up a full 48% of Charedi household income. Today, it stands at 27% of income alone. The change is due to an increased entry into the labor market, mainly by Charedi women, and an increase in the number of income providers among Charedi households from 0.76 on average to 1.32. This increase is meaningful. But is it enough?

If the current change trend continues at a similar rate, the economic impact of Charedim will still require either a dramatic reduction of Israel’s budget or a dramatic tax hike (there might be other ways of improving our economic situations, such as slashing regulations, but these are unlikely to be dramatic enough to compensate). Glancing at the data, a quantitative doubling of the Charedi population in some 16 years will result in a doubling of households with low incomes and a significant reduction in tax income to state coffers. The financing of Charedi needs by the general public purse will also be doubled, not including the upcoming budgetary demands of Charedi MKs in the incoming government.

The financing of Charedi needs by the general public purse will also be doubled, not including the upcoming budgetary demands of Charedi MKs in the incoming government

It is worth noting that although the audience at the conference in question was mostly Charedi, no one felt under attack or offended by the presentation. The message that the governor wished to convey was not patronizing or reprimanding but analytical and matter-of-factly. He did not tell people what to do with the data but to present things as they were. What somebody does with this data is his business. Whoever thinks it is possible to finance the Torah world by constantly raising taxes, which fall predominantly on the upper deciles (where the proportion of Charedim is slim to non-existent) will continue the current policy ad infinitum. However, those who fear that this is not a sustainable plan will look for ways to increase Charedi contributions to the economy.

Low Socioeconomic Class or Sectoral Issue?

As mentioned above, the reaction of many Charedi outlets to similar claims is that they are somehow antisemitic. No one would think to contrast the economic contribution of Yerucham and Sderot (peripheral cities in the south of Israel) with their burden on the economy or holding conferences and making headlines about it. This is how, for example, Knesset member Yisrael Eichler responded to the governor’s words:

Counting the Charedi public separately is fundamentally antisemitic, and of greater concern is the demographic census designed to expose the alleged threat of the increase in the number of Charedi children, which is the result of animosity and hostility towards the Charedi public. In its great conceit, Reform Judaism has been classifying Charedim as a different category for many years. This is nothing but antisemitic racism that portrays Charedim as an existential threat.[9]

In every economy, there will obviously be some in the lower deciles, and it would be ridiculous to say they are to blame for slowing down the economy

According to this logic, the Charedim do belong to the bottom deciles, but they should not be blamed for the economic slowdown. In every economy, there will obviously be some in the lower deciles, and it would be ridiculous to say they are to blame for slowing down the economy. In other words, there will always be low-wage jobs in the economy, and Charedim manning these jobs should not be cause for complaint, just as we would never complain about non-Charedim in the bottom decile though their economic contribution is like that of Charedi society.

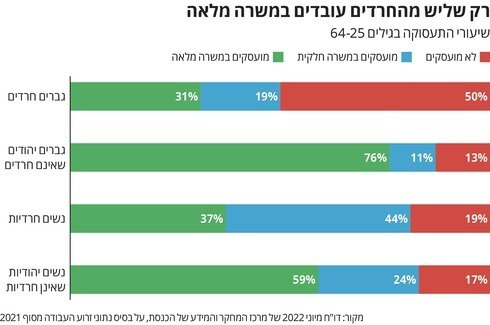

However, is the low contribution of the Charedim to the economy only because the Charedim are employed in low-paid jobs? Of course, this is far from the case. In the following graph, we see a comparison of the percentage of participation in the labor market between different sectors of Israeli society:

The graph spells things out pretty clearly: The low contribution of Charedim to the economy is simply because they work less. We should be the first to concede this. It does not imply that we have an obligation, legal or moral; this, together with the position of halacha (which is pretty explicit about going to work), is a matter of opinion. However, the fact should dispel the claim that identifying the Charedim as a group with low economic contribution is motivated by hatred. There are valid reasons to focus on this group. The low regard for Charedi society is not only due to the professions they engage in but to the simple fact that they choose to work less. The easiest thing to do to improve the economic situation of Charedi society and the entire country is to encourage Charedim to work more. In the process, this will also preserve, rather than damage, the Yeshiva world.

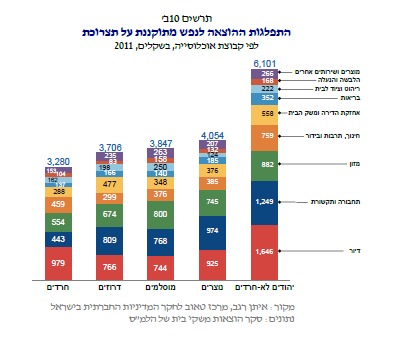

Speaking of populist claims, another claim that should be dismissed once and for all is that the differences between the direct tax contribution of Charedi society and that of general society are dwarfed by the indirect taxes the Charedim pay in VAT: since Charedim have larger families, they consume more, thereby paying more indirect taxes. This hardly deserves refutation, but, unfortunately, it is heard repeatedly. To disprove it is remarkably simple: those who earn less spend less and save less. Charedi society earns less and, as a result, has less purchasing and investment power. To convince those who still doubt this, the graph below represents standardized expenditure per capita (taking into account the relatively low expenditure per capita of larger families) by sector:

Charedi households have the lowest standardized per capita expenditure, at about 3,280 ILS, compared with Muslims and Druze households which spend about 3,800 ILS, and non-Charedi Jews, who spend an impressive 6,101 ILS.[10] Thus, even concerning indirect taxes, Charedim contribute substantially less to state coffers.

***

Throughout this short piece, I have repeatedly emphasized that refraining from work is not necessarily a moral problem. In conclusion, I will add a short reflection.

While condemnation from the outside is often unjustified, I think that we, the Charedim themselves, need to make a reckoning. This should begin as a Torah reckoning. On the one hand, the Torah does not confer a mitzvah on padding state coffers or becoming wealthy members of the top decile of earners. On the other, it is a mitzvah to work and to be self-reliant, and we cannot ignore the fact that our current model neglects this basic Torah and ethical responsibility.

Furthermore, it is certainly possible to argue that there is something immoral about refusing to contribute to the state economy while demanding that others subsidize one’s choices. On the other hand, there’s no sin in taking what welfare states offer under the assumption that most people will want to work, fight their way to the top socioeconomic deciles, and pay taxes accordingly. People choose to be artists and philosophers and a range of occupations that leave them relatively impoverished, and society is generally happy to foot the bill.

My argument in this article is not a moral one but rather an instrumental claim stating that as the proportion of Charedim in the population grows, the services available to citizens will likely diminish

These discussions need to take place. In this article, however, I have tried to provide them with context. My argument, therefore, is not a moral one but rather an instrumental claim that as the proportion of Charedim in the population grows, the services available to citizens will likely diminish. The equation is extremely simple.

Politicians and journalists often express themselves as follows: “The state will have to dig deeper into its pockets to take care of X.” X can be disabled people, single mothers, or preschool education; it can also be Yeshiva institutions and Torah students. In all such cases, it is truly essential to realize that a state has no “deep pockets.” All it has is a certain percentage of the public’s production. If fewer people work, that means less production, and less production means less state revenue. A high percentage of those who discuss government budgeting ignore these elementary facts (and not only in the Charedi context).

Those who care about the core values of Charedi society—Torah study, the continued thriving of the Yeshiva world, and the general well-being of Jewish life in Israel—should pay attention to the basic data and make their economic decisions accordingly.

To conclude, I wish to quote the words of my friend Shlomo Teitelbaum, published in the economic journal “Calcalist,” in which he called for an equation between power and responsibility and urged Charedi society to cease seeing itself as a minority:

Both Charedi and secular societies benefit from Charedi society’s shirking of its responsibility. Secular Israelis do not need to experience the discomfort of Charedi power, while Charedim can continue to claim the status of a persecuted minority, even though they have been in power for years. Every day, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to escape reality. Population growth is already taking its toll, and the recent elections, alongside our political chaos, have given the Charedim extraordinary power. They cannot maintain the perception that they are in power only to protect their basic rights.[11]

Charedi society continues to grow. A growing Charedi population exacerbates the gap between low tax income and high government expenditure. The data suggest that absent significant change, the state treasury will be unable to sustain the Torah world and the welfare system of benefits, no matter how strong the Charedim in the Knesset become.[12] A responsibility-based mindset should be adopted, both in Charedi and Israeli society.

[1] Among others, by the OECD.

[2] https://www.themarker.com/news/politics/2022-09-16/ty-article-magazine/.premium/00000183-4180-dfd0-a5f7-4f836e1d0000.

[3] https://bizzness.net/%D7%94%D7%A0%D7%92%D7%99%D7%93-%D7%A6%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%9A-%D7%9C%D7%94%D7%AA%D7%9B%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%9F-.

[4] There are four main methods for defining the Charedi population, which are used to estimate its size and characteristics: Voting patterns: identifying the population according to geographical distribution based on voting patterns for Charedi parties. Last school: as part of the CBS surveys, respondents are asked what was the last school they attended. A household is defined as Charedi if at least one of the spouses attended a Charedi yeshiva or seminary. Self-determination: a direct question presented to the sample population being surveyed, in which the respondent is asked to state the level of his religiosity. One of the possibilities is “Charedi.” Education system of schools: an estimate of the size of the population that studies or has studied in institutions within the framework of a Charedi or independent system, according to the Ministry of Education’s data on those studying in educational institutions. According to this method, the school choice in Israel is a reliable indicator for identifying a person’s level of religiosity. While the methods of measurement differ, they are not significant for our purposes or in terms of group size.

[5] From 2000 to 2015, the number of Charedi students increased from approximately 212,000 to 404,000, an increase of approximately 89%; Neri Horowitz, The Charedi society – 2016 status report (Jerusalem: Charedi Institute for Policy Studies, August 2016).

[6] The data are according to the calculations of the Central Bureau of Statistics, from Lee Kahaner and Gilad Malach, Yearbook of Charedi society in Israel 2021 (Jerusalem: The Israeli Institute of Democracy, 2021).

[7] A household is a family unit consisting of one or two income providers and their children. Charedi society is 13% percent of the population of the State of Israel according to the number of persons, but only 7% percent of the number of households.

[8] See https://www.boi.org.il/he/NewsAndPublications/PressReleases/Documents/%D7%9E%D7%A6%D7%92%D7%AA%20%D7%94%D7%A0%D7%92%D7%99%D7%93%20%D7%9B%D7%A0%D7%A1%20%D7%93%D7%9E%D7%A8%D7%A7%D7%A8.pdf.

[9] https://www.inn.co.il/news/422997.

[10] Eitan Regev, Making ends meet – Income, Expenses and Savings of Households in Israel (Jerusalem: The Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, December 2014).

[11] https://www.calcalist.co.il/local_news/article/hyneuhsho.

[12] There is also a risk of a political reaction, which will cause the Charedi parties to return to the opposition benches, as was the case not long ago.

Photo by: Nizzan Zvi Cohen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In an otherwise insightful article, there is one glaring item that can be badly misinterpreted. Saying that there a bottom decile or quartile in every population is an absolute truism.

However, to be concrete, consider both a country where a quarter of the population averages 350K, 200K, 150K and 90K, respectively and another country where the numbers are 350K, 200k, 150K and 40K respectively. Both have a bottom quartile, but the latter probably presents a larger problem.

As much as I admire the dedication to Torah learning and a complete Torah life one finds in the Chareidi community, I am dismayed by its low ambition to engage in the working world. Many seem to be as repulsed by the concept of work as was Maynard G. Krebs.

Why did this happen? This is a relatively new phenomenon in Jewish history theoretically modeled after the ancient roles of the Levites and Yisacharites.

One reason may be because placing the Talmud Chochom at the apex of society became the only supreme objective of every family, often motivated by future Shiduch considerations, that lesser capable learners were eternally doomed to a lower rung on the Chareidi ladder.

In short, if you worked, you were stigmatized as a second-class citizen.

The solution to this problem is to adjust the hierarchy where Zevulun is admired, honored and revered as is Yisochor.

The Hirschian model of Torah Im Derech Eretz should be reinvestigated as it elevates the average working, yet fully-committed, Baal Habayis to the highest of level of admiration and honor without sacrificing maximum Talmud Torah.