A close friend told me about how she limped into her humble abode after attending a recent gala affair. Within less than a minute her contact lenses were happily ensconced in her lenses case and her glasses re-perched on her nose. Her fresh-from-the-shaytel-macher-shaytel was resting slightly askew on the shaytel head, while her comfortable-as-an-old-shoe-snood was on her head. Her high-heeled shoes lay sprawled in the corner while her feet luxuriated in her delicious slippers. Then came a knock on the door. My friend said it took her a second to realize why the eyes of the young girl, who had come to bring something my friend had left in her ride’s car, widened in surprise at the sight of her. Then she caught a glimpse of herself in the mirror in the hall and understood. In the two minutes since she had walked in the front door, she had metamorphosed from Cinderalla at the ball to Cinderella, scullery maid.

In the two minutes since she had walked in the front door she had metamorphosed from Cinderalla at the ball to Cinderella, scullery maid

The anecdote makes a great metaphor for the contrast between the public and private spheres. All those beautifying agents that constrict, confine, cramp, compress, crush and contour are everyday representations of the inhibition that the public arena imposes in all areas of our lives. Walking outside our front door always involves some sort of posturing and pretension—even when we are wearing sneakers.

This is true even of the most honest and authentic among us. We all possess the dual personality of the private and the public, a public face and a private face. The relationship between the two varies from person to person, but their fundamental difference is common to the human condition per se. “Man sees what his eyes behold, but Hashem sees into the heart” (I Shmuel 16:7)—and even our seeing “what our eyes behold” is partial at best. The clothing we wear, whether physical, verbal or mental, hides far more of us than it reveals; we cannot truly know the private faces of individuals, even those most familiar to us in the public space. “Kol ha’adam kozev” said David HaMelech in Tehillim (116:11). This doesn’t mean that all people are pathological liars. It means, rather, that there is an intrinsic deception endemic to the human condition. We often hear neighbors of some nondescript person suddenly accused of a crime quoted as mumbling wonderingly, “Who would have guessed?” The truth is that we might think we know somebody fairly well, only to be surprised at discovering a new aspect that we simply never saw.

The separation between the private and the public is not wholly negative. Not telling the whole truth definitely has its place, and it serves as a crucial social instrument. A person’s private life includes oscillating states of mind, complex personal relationships, struggles of faith, inner drives and passions, the challenges of raising kids or maintaining marital harmony, and who knows what else. But in our public lives, we need to get to work every day on time, to do the job, and to maintain peace. Absent the boundary dividing between the private and the public would cause nothing less than social chaos. I don’t know actually want to know my neighbor’s innermost struggles or dreams or hopes. My polite smile on my way to take out the garbage, as part of a general public sphere affectation we tend to adopt, is good for me and good for others too. It keeps society functioning without getting bogged down with the emotional burden of the close and the intimate.

Absent the boundary dividing between the private and the public would cause nothing less than social chaos.

The ability to keep the inner parts of our world private protects us. It allows us to maintain a healthy public image that remains stable irrespective of the storms raging inside and spares us the involvement in the personal storms of those around us. There is a reason why the value of privacy, which defines the boundary between the public and the private, is so lauded as a social virtue. It gives us space to “be ourselves” without concern for curious onlookers while shielding us from uninvited exposure to the inner lives of others—exposure that would break the peace of our social environment and rattle our own internal harmony.

Yet, despite its great value, the distinction between the public and the private can also be a hazard. Possessing a superficial, inauthentic posture comes with an inherent risk that our public domain might erode our private domain. The more dominant the public face, the more our private face—our home—becomes endangered.

Borders and Boundaries

What makes a private arena private is that it is not public. Whether they are made of brick, concrete or sheets strung up on a string, the purpose of the walls that delineate a private sphere from a public one is to create an inner space that is protected not only from the elements but from the seeing eyes and hearing ears of the public arena.

This is true of course on a simple day-to-day level: many activities are perfectly appropriate in a private arena but would not be so in a public one. Chazal sometimes even specify actions that should be limited to the private domain: “One who eats in the marketplace resembles a dog” (Kiddushin 40b). But on a more fundamental level, if the public arena demands a level of pomp and pretension, it is the private arena that allows us to access our deeper, truer, and more authentic selves. Indeed, people who spend all their time in the public sphere sometimes complain that the public sphere not only silences one’s inner self, it might even strangle it completely.

People who spend all their time in the public sphere sometimes complain that the public sphere not only silences one’s inner self, it might even strangle it completely.

The Rambam thus teaches us that a person “gains most of his wisdom when he learns at night.” Even the Beis HaMidrash, that fortress of truth, is a “public space” full of noise, people, and movement. It is at night, in quiet solitude, that one has the greatest connection to true wisdom.

Yet, instead of cherishing the oasis of authenticity that the home offers, in our modern age we spend more and more of our time escaping the home. For the best of reasons—work, exercise, fun, appointments, comradeship—we spend less and less of our time at home, and more and more of it out in the public. This is true both literally—outside the walls of our home—and figuratively, out in the public domain of the Internet.

Instead of cherishing the oasis of authenticity that the home offers, in our modern age we spend more and more of our time escaping the home.

We seem to find the call of the public arena irresistible. Perhaps we prefer to live in a world peopled by one dimensional, happy-faced mannequins whose lives are full of adventures (culinary and otherwise) that we can access with a flick of our keyboard. And there is certainly something appealing (and ego-stroking) in the solid accomplishments that work-life offers, by contrast with running a home where a cooked meal or empty laundry basket are washed away hourly by the tsunami of life. It is more compelling to cultivate “social status” than invest in building one’s essence, and less demanding to follow the masses than to forge an individual path to Hashem as the privacy and individuality of home life demands. It takes less out of a person to put up a façade than to have the courage to be authentic.

And then comes Chanukah.

Chanukah: The Victory of the Private Domain

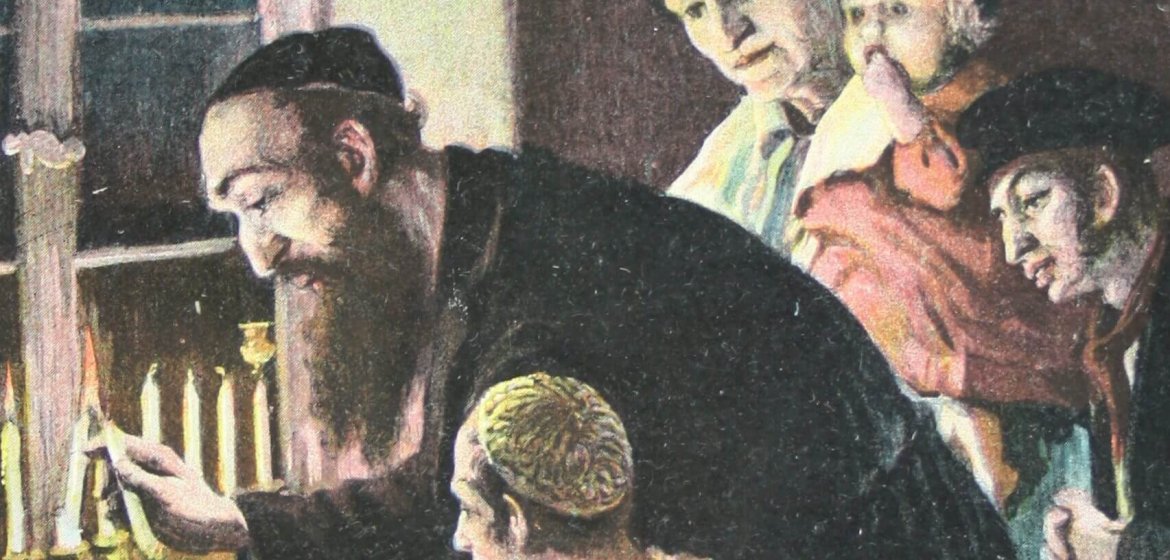

Chanukah is a celebration of the home; on Chanukah, the home, whose strength draws specifically from its hiddenness from the public eye, does the world a favor and allows some of its brilliant light to shine out into the public realm.

This message is brought out powerfully in the phrasing of Al Hanissim. It was indeed a military miracle that the strong fell into the hands of the weak, but, one wonders, what do the words “many into the hands of the few” add to that miracle? Generally, the strong are many—that is part of what makes them strong (tug of war competitions prove the point). And how does it add to the military miracle that the impure fell into the hands of the pure, or the righteous into the hands of the wicked? Being righteous or pure does not necessarily limit your military prowess.

Rabbi Moshe Shapira, zt”l, explained that the reason for this wording is that Al Hanissim celebrates not only the actual military triumph over the Greeks, but even the triumph of specifically those qualities that generally do not win the day in this world. The exact qualities that generally put one at the bottom of the totem pole of worldly power suddenly came out on top. Strength, might, power, brawn, stature, renown—all these retreated in face of weakness, smallness, and purity. In this instance, the qualities of might were vanquished by the qualities of right. The victory of the few over the many is the victory of the inner over the superficial, the authentic over the strong. The home vanquishes the public domain and lights it up.

The exact qualities that generally put one at the bottom of the totem pole of worldly power suddenly came out on top. Strength, might, power, brawn, stature, renown—all these retreated in face of weakness, smallness and purity. In this instance, the qualities of might were vanquished by the qualities of right

No matter how many times we hear it, this message somehow fails to sink in. In Judaism, it is not a plus to be mighty, strong, prominent, or high-flying: “Not because of your abundance over all the nations has God desired in you and chosen you, but because you are the fewest of all the nations”. It is specifically “weakness” and “fewness” that gives the winning edge in Judaism. Perhaps this is because when I am “weak” and “few” there is room for Hashem in my life. I have no illusions that I am running the world or that everything is in my control. The authenticity of human living, with its muddling complexities and inherent frailty, makes space for the Shechinah to reside.

Chanukah and Women

The Chanukah candles that shine their light specifically from the home—from the inner sanctum of the Jewish private domain—raise a point worthy of consideration: the feminine nature of the Chanukah festival.

While people tend to get up in arms about this, women’s role in Judaism is in many ways less prestigious, less powerful, and certainly less prominent than that of men. Instead of expending huge amounts of energy trying to prove that this isn’t true—whether by demonstrating that the roles are in fact equal or by reforming the roles to create artificial equality—perhaps we can take a mature step back and realize that even if true, this is not necessarily a bad thing. From a spiritual-internal perspective, it might even be a virtue and an advantage. Perhaps it is specifically the private, more feminine arena, far from the public eye, which holds the key to spiritual triumph.

Women’s role in Judaism is in many ways less prestigious, less powerful and certainly less prominent than that of men. Instead of expending huge amounts of energy trying to prove that this isn’t true—whether by demonstrating that the roles are in fact equal or by reforming the roles to create an artificial equality.

In Judaism, the female persona is intimately bound up with the home, the quintessential private realm. “Behold she is in the tent” (Bereishis 18:9), Avraham said in praise of Sarah to the angels. “I call her not my wife” (Shabbos 118b), Rabbi Yosi declared of his wife, “but rather my home.” There are many other sources and references that we can adduce, but the principle seems clear enough, rooted both in textual sources and in a rich, living tradition.

It is not in the public sphere, but in the home—that fortress of internality—where a person meets his real self and where real growth germinates. This idea is born out in a breathtakingly beautiful insight revealed in a seemingly prosaic halachic principle about the prohibition to carry something from a public domain to a private domain on Shabbos. While a public domain has a ceiling of ten tefachim—the airspace above ten tefachim is no longer considered a public domain—a private domain “stretches up to the heavens” (Shabbos 7a). In a halachic sense, the Gemara can thus discuss whether is it considered “carrying” if one tossed an item from one private domain to another over the public domain, but the object remained ten tefachim above the ground throughout. But on another level, the same principle—that the private domain extends to the heavens—is at root a profound statement of reality.

It is only in the chelkas yachid, the private realm of the home, that one can truly soar. Not weighed down by outside demands and expectations, by the conniving and contriving of the social arena, one is free to access the Truth of all truths.

There is much to be accomplished in the world outside our front door; but no matter how much we hustle and bustle, no matter how much noise and action we stir up or how high the skyscrapers rise, the intrinsic superficiality of the public realm always places a cap on the heights one can reach. It is only in the chelkas yachid, the private realm of the home, that one can truly soar. Not weighed down by outside demands and expectations, by the conniving and contriving of the social arena, one is free to access the Truth of all truths.

This is the Truth that stands at the core of the Chanukah festival. And by contrast with the ubiquitously public nature of victory celebrations everywhere, this is why the Chanukah victory is celebrated in the home.

The Greek decrees that targeted Shabbos, Bris Milah, and the Jewish calendar, were an attack against the inner core of our Jewish identity. Our response, enshrined in the lighting of Chanukah candles, is to find strength in the purity of our homes. Somebody who lacks a home—or, in the symbolic sense of Rabbi Yosi, somebody who lacks the modesty and internality of the feminine spirit—cannot kindle the Chanukah lights. Despite modern attempts to transfer the mitzvah into the town square, the principal fulfillment remains squarely in the private domain. Only there can we rise above the fray, reinforcing who we are and what we represent from within the Jewish home.

The House of Yaakov

It is fascinating to note that not only is the woman closely entwined with the idea of the internally focused ohel, but so is Yaakov Avinu. The Torah tells that by contrast with Eisav the hunter—cunning, predatory, powerful, whose sphere of activity is in the field—Yaakov sits cloistered in his ohel (Bereishis 25:27), deep within the tent, delving into the wisdom accessible only in that private place.

Yaakov and Eisav’s diametrically opposed worldviews come to a head in the historic encounter the Torah narrates. Deep within their interchange lies the eternal struggle which continues to this day in our own minds and hearts. In a sudden burst of friendliness, Eisav asks Yaakov to join forces with him: “Let us travel and journey, and I will journey with you” (Bereishis 33:12). Eisav, the man of the field, declares yesh li rav, “I have plenty” (33:9). I am strong. I am powerful. Do you know what the two of us can accomplish together? But Yaakov, the ish ohalim, declines the offer: “va’ani etnahela l’itii”, he says—I will go ahead slowly, accommodating myself to the needs of my children and my flock.

How distant is the sentiment articulated by Yaakov from the underlying message of our own world, urging us to success, to ambition, to self-fulfillment? Yaakov declares that his life is not about conquest, acquisition, and production. Translated into today’s parlance, Yaakov’s statement would surely bring on a Sheryl Sandberg induced cringe. As COO of Facebook, Sandberg’s best-selling book urges women to “lean-in” to success. And what can be less “leaning in” than making one’s progress in life contingent on responsibilities towards others? Where’s the sense of ambition? The drive? The ego? Yaakov sets these aside and finds his fulfillment in the small light he kindles in his home.

Its radiance emanates from within the home—from the private domain’s “weak” and “few” rather than the multitudinous and the mighty of the public zone—and lights up the darkness outside

Dwelling in the tent is not only a physical description alone; it is also a state of mind. Most of Yaakov Avinu’s life was spent far outside the ohel and dealing (in kind) with very un-ohel like people. Today, many women are likewise impelled by life circumstances to be out there in the world. But the ohel is something that the Jewish people in general, and Jewish women in particular, have carried with them throughout history—wherever they found themselves physically—thanking Hashem for the light they carry within that shines out into the darkness.

And this is what we do, too, as we kindle the Chanukah lights. Our cherished private domain has a wider, greater calling, an influence that spreads far beyond the confines of its walls. The necessary separation between private and public is not hermetic. The light burst forth from within the ohel—within the tent of Yaakov Avinu, within the Jewish home—and lights up the entire world.

This is the lesson of the Chanukah lights. We light the menorah inside the house, but we place it at the window or the doorway. Its radiance emanates from within the home—from the private domain’s “weak” and “few” rather than the multitudinous and the mighty of the public zone—and lights up the darkness outside.

The ideas in this article were drawn from the Torah of Rav Moshe Shapiro, zt”l, as written up in Reflections and Introspections, Chanuka and Purim, by Rabbi Moshe Antebe

An earlier version of this article appeared in the “Family First” supplement of Mishpacha Magazine.