Much ink has been spilled on the pages of “Tzarich Iyun” on the question of Charedi men at work—“working Charedim,” as they are commonly referred to in Israel. Numerous articles have discussed the social and spiritual status of the typical yeshiva man who leaves the Torah study hall for the workplace, the difficulty of being far from his sheltered milieu, the educational challenges for children of working parents, and plenty more.[1] However, many of these questions are often formulated as sociological problems: how to deal with a society that disparages men at work or, at the very least, treats them as second-class. Proposed solutions to sociology-oriented challenges tend to the technical and most focus on reconnecting working Charedi men to their “spiritual core,” whether by establishing programs that attract them to Torah study or by other means.

Certainly, I do not dismiss the sociological aspects of the matter of working Charedi men, nor belittle the proposed solutions. Yet, I wish to focus on the issue from a different point of view—a more philosophical or theological perspective rather than the sociological one. My argument is that the social difficulties of working Charedim are symptoms of deep theological distress arising from the process of going to work. The social difficulties are not the result of moving from one society to another—though this is a factor—but derive mainly from a profound incompatibility between the worldview into which Charedi boys and young men are inculcated and their new situation as working men. Charedi theology leaves precious little space for the Charedi man at work. The difficulties he encounters are thus rooted in religious angst rather than sociological nonconformism.

The conflict between the Charedi contempt for the secular world and his new reality creates a value-laden tension that is not readily resolved

The Charedi strategy for coping with the secular challenge is seclusion and withdrawal—isolation from the cultural influence of secularism and exposure to its ideas and principles. Lectures on Jewish thought and ideology are filled with contempt for the secular world and the values it stands for. Secularism, the argument goes, including the entire gamut of secular life, has nothing to offer, and we must close ourselves off from the temptations it poses.

This strategy has proven itself for most of the community. It is very easy to convince those who have never encountered the world of secular values that it is devoid of value. However, when the Charedi individual takes a meaningful step or two outside his sheltered milieu, engaging with the outside world and sharing its experiences, he often begins to integrate parts of general culture and worldview as part of his lifestyle. This can include participation in general culture, greater investment in personal grooming, and a change of attitude toward the secular itself. The conflict between the Charedi contempt for the secular world and his new reality creates a value-laden tension that is not readily resolved.

Suddenly, the working Charedi man experiences a conflict between traditional community and family values and new individual values of self-actualization and human rights. Another common tension relates to simply “living the good life.” According to Charedi tradition, the concept of the “good life”—living a meaningful, engaging, aesthetic, pleasant life in the worldly sense—holds little or no value. This world is but a vestibule for arriving at the World to Come; it cannot be “good.” In contrast with this worldview, in today’s Western world, a person’s ambition to establish a large company, play a significant civic role, live in a luxurious home, to raise successful children who will have an entire life replete with a variety of human experience—all these are considered causes worth striving for.

In a nutshell, it seems to me that the main struggle of working Charedim is the conflict between the Charedi notion of a meaningless world and the ideal of the good life he encounters outside the walls of Charedi society. At a time when Charedi men are under growing pressure, external (from Israeli society) and even internal (a host of personal reasons), to join the workforce, there is a real need for fresh thought.

Vanity of Vanities

Some time ago, a video was circulated on Charedi WhatsApp groups in which the head of the Ateret Shlomo Institutions, Rabbi Sholom Ber Sorotzkin, was seen standing on a platform at the foot of the Burj Khalifa tower in Dubai. Addressing a small crowd of participants at a glittering event in the wealthy Arab principality, his powerful voice boomed with pathos as he exclaimed that “all we see to our right and our left is vanity. Only the Torah is of any significance.” The humorous irony of using such Yeshiva-style clichés against the richly decorated background of Dubai was not lost on the discerning WhatsApp audience.

The fundamental difference between Rabbi Sorotzkin and Charedim at work is their attitude toward the physical, earthly reality. Does Sorotzkin live with the feeling that this world is vanity and meaningless, or does he feel uncomfortable when confronted by this attitude? The difference between working Charedim and the rabbi is not the number of hours spent studying Torah. Being a person who manages a wide network of institutions and raises funds for its keep, Rabbi Sorotzkin is no less a “working Charedi” than the subjects of this piece. Yet, we don’t look at him this way because of his attitude—at least in their rhetoric—to the material world. The term “Working Charedim” refers to those individuals who value the world—the working world, the world outside the study hall—and are uncomfortable with the wholesale devaluation of the earthly prevalent in Charedi society.

The theology, I wish to emphasize, makes a difference. The hierarchy between the learner and the worker is not just a social matter—learning is socially superior to working—but draws from a metaphysical hierarchy between the two that places learning on a pedestal at the specific expense of working. It is not just that Torah study realizes the purpose of the world’s creation, but rather that the entire creation serves as a decorative background for Torah study. The problem of the Charedi worker is thus not merely “feeling second-class,” but that the theology he digests with his mother’s milk declares that he is occupied with futile vanity while repudiating the lofty engagement with the very purpose of creation. Mentally, it’s a tough place to be in.

A person who internalized his Charedi education yet finds himself engaged in the vanities—notwithstanding multiple Torah sources that might point to the contrary, the expression “havlei olam hazeh,” vanities of this world, exemplifies the Charedi approach—is faced with a dilemma, two ways of coping with his situation. One is the Zevulun track; the second is plain nihilism.

Those who tread it adopt a cognitive dissonance, preaching a moral life in line with Charedi principles yet living a nihilistic life that allows occupation with earthly vanities without experiencing constant pangs of guilt

The Zevulun track justifies occupation with the worldly by employing all available resources for the sake of Torah study; if you don’t have the merit of full-time Torah study, at least you can support and empower those who do. The second track involves developing a cynical and dismissive attitude towards the Torah world, even while continuing to speak its language. Those who tread it adopt a cognitive dissonance, preaching a moral life in line with Charedi principles yet living a nihilistic life that allows occupation with earthly vanities without experiencing constant pangs of guilt. You have to be an insider to know them, but many, unfortunately, follow this road of fulfillment.

Such individuals (the latter group) continue to see the materialistic life of their choice as a crude and empty existence; they will never read high literature or go to the theatre. In this context, we might encounter people eating meat with vulgar hedonism while half-mockingly repeating the mantra “Reb Shaya ben Reb Moshe,” intended to somehow sanctify the act of eating. In truth, the act of eating lacks all aesthetics and refinement, and the “Reb Shaya” mantra leaves it hopefully unredeemed, but this is the case almost by definition. Such individuals do not wish to adopt the Western concept of the “good life” but to live a life of “vanity of vanities.”

Their world, indeed, is empty and vain, yet they chose it over the sufferings of the Beis Midrash. Some have pointed out to the relative prevalence of this type of person among Charedi journalists, those who peddle the Charedi worldview, sometimes even extreme versions of it, without believing a word of what they say.[2] The truth, however, is that the phenomenon is far broader than the narrow sphere of Charedi journalism.

Both categories of working Charedim can thus moderate the social symptoms of going to work. If they make it rich, they will receive the stature of a respected “gvir” (philanthropist), and if not, they can still be “Torah supporters” (Tomchei Torah), dedicating their means and energies to those who live the ideal. Sometimes, however, a working Charedi individual will espouse a concrete view that gives credence and value to the secular environment and productive action within it. He will start believing it, find Torah sources to ground it, and even begin preaching it. And this is where the actual conflict begins.

Rejecting the Worldly

The social situation, discussed ad nauseam, of working Charedim as second-class citizens, is thus challenging not only due to the condescending views of friends and neighbors but also due to a sharp internal conflict that working Charedim experience with themselves.

This insight clarifies why Charedi members of society who started their adult life on a path of work (many Chassidim fit the bill) or communal activism experience a far lesser degree of tension. They feel no dissonance in the face of the notion that worldly life is empty; on the contrary, they are modeled after this style of living. On the other hand, those who were destined to be full residents of the Beis Midrash and chose to change course and go to work cannot accept with equanimity the futility of this world. Their choice of a working life creates a gap between the worldview they were brought up with and their actual lives.

[T]hose who were destined to be full residents of the Beis Midrash and chose to change course and go to work cannot accept with equanimity the futility of this world. Their choice of a working life creates a gap between the worldview they were brought up with and their actual lives

Similarly, a working Charedi individual finds it difficult to find a suitable educational institution that will maintain high standards of Torah education while ensuring his children (boys) receive the basic skills to participate in greater society, saving them the hardships that he experienced. The hardship is far more profound than technical issues alone, such as English and mathematics skills that need to be made up at a ripe old age. While his journey might have undermined the integrity of his Charedi worldview, the working Charedi parent will agonize over how to educate his child. For many, the new Mamach schools—state-run schools for Charedim—are not a legitimate option.

The problem of working Charedim, or at least the major problem on which I have focussed, can thus be dubbed “the problem of dissatisfaction with the rejection of this worldly life.” It is not a unique problem for employed Charedim, and can affect those deep in Kollel, too—though it is more common among them. Of course, many Charedi men work for a living, for one reason or another, and do not experience any difficulties. On the other hand, not a few Charedi men immersed in the Torah world experience the same difficulties experienced by their working peers. The discomfort with a theology that dismisses this world does not necessarily involve an actual departure from the Kollel.

Solving the “Problem of Working Charedim”

Most discussions on the challenges of working Charedim are predicated on sociological premises, so the proposed solutions mainly address social issues alone. Such solutions include establishing alternative Batei Midrash catering for this group, developing an alternative rabbinical leadership, creative support groups for students and other sub-groups, and forming compatible educational institutions—alongside similar initiatives.

In the theological field, however, precious little has been done. Of course, we are all familiar with numerous quotes from the Talmudic Sages that place a stamp of approval on going to work: “Beautiful is the study of Torah with derech eretz, for the striving of both makes one forget sin; and all Torah that does not have work accompanying it is ultimately nullified and drags [in] sin” (Avos 2:1). Yet, these sayings and quotations are yet to coalesce into a complete theological system of thought.

A resurgence of spiritual concepts that have vanished from the Charedi lexicon street over the past decades is beginning, but they remain far from a comprehensive and inclusive ideology. The only religious world that working Charedim know remains that of R. Shalom Ber Sorotzkin—a world in which everything that is not Torah is “vanity of vanities.” So long as he is immersed in such vanities, he cannot but develop a sense of bitterness, especially towards those who claim that the world is “vanity of vanities” but continue to pursue it with vigor.

The entry of Charedim into the labor market is accompanied by social and community changes that threaten to undermine fundamental tenets of Charedi education, beginning with the weakening of Charedi society’s walls of separation and including the development of an appreciation for the Western world and validation of earthly and practical life. This phenomenon requires a revision or a rethinking of some basic principles of current Charedi education. If we want this trend to be perpetuated—and we should want this, both for the vitality and sustainability of Charedi society and for the State of Israel—we need to look at past experiences (such as PAI, Poalei Agudat Israel) that failed the test of time, and learn the lesson: without spiritual strength and a cohesive worldview, you cannot make it in the long run.

The “Tzarich Iyun” platform on which this article is published is a good beginning; absent it, where else could a piece such as this appear? Yet, it remains a beginning alone. We need rabbis, scholars, articles, and books that will develop the missing ideology

The “Tzarich Iyun” platform on which this article is published is a good beginning; absent it, where else could a piece such as this appear? Yet, it remains a beginning alone. We need rabbis, scholars, articles, and books that will develop the missing ideology. Following this, we need communities and associations, schools, and other public institutions that will implement and realize it.

A developed and robust worldview will form the basis communities of “working Charedim”—whether they are actually at work or not—whose unity will transcend sociological angst and will include a shared worldview that combines Torah life with Derech Eretz. If a community is built on shared values, it will be more durable and of far higher quality than one built on a common rejection of the mainstream. Such a spiritual association will also enable tangible achievements on the ground, such as educational institutions and synagogues. A claim predicated on a comprehensive and coherent worldview, and religious belief system is substantively different from one made in the name of some common social grievance. The former is infinitely stronger.

Forming a New Elite

Moving toward the practical, we must invest in cultivating an elite among the Charedi “working class.” Up until now, the usual pattern of action in dealing with questions of working Charedim has been the creation of Torah frameworks facilitating a sense of belonging to the traditional Beis Midrash. This is important but not sufficient. Since we are dealing with a theological question, it is appropriate to direct energy in the direction of creating Batei Midrash for a rabbinical elite, which will focus on composing and formulating a worldview that gives Torah value to human labor in an earthly reality and build a spiritual leadership for the community of wording Charedim.

Rabbis with a listening ear—there are plenty around, and credit to them—are insufficient. We need a line of scholars and thinkers that will provide the comprehensive ideology currently missing. They will not merely serve to answer questions of halacha and sociology but will act as the cutting edge in the creation of a complete religious and spiritual worldview. I, for one, eagerly await their achievements.

[1] See also articles published on Tzarich Iyun [Hebrwe] by Moishi Rosenzweig and Mati Horvitz [Hebrew], which touch on the points I raise.

[2] See https://betochami.blogspot.com/2022/01/blog-post.html?fbclid=IwAR3R5lotMi3gXjxT58XQgpfFlKQbk0X3IU8HtWGv2t76iDUWOKt5EsUUPbg [Hebrew].

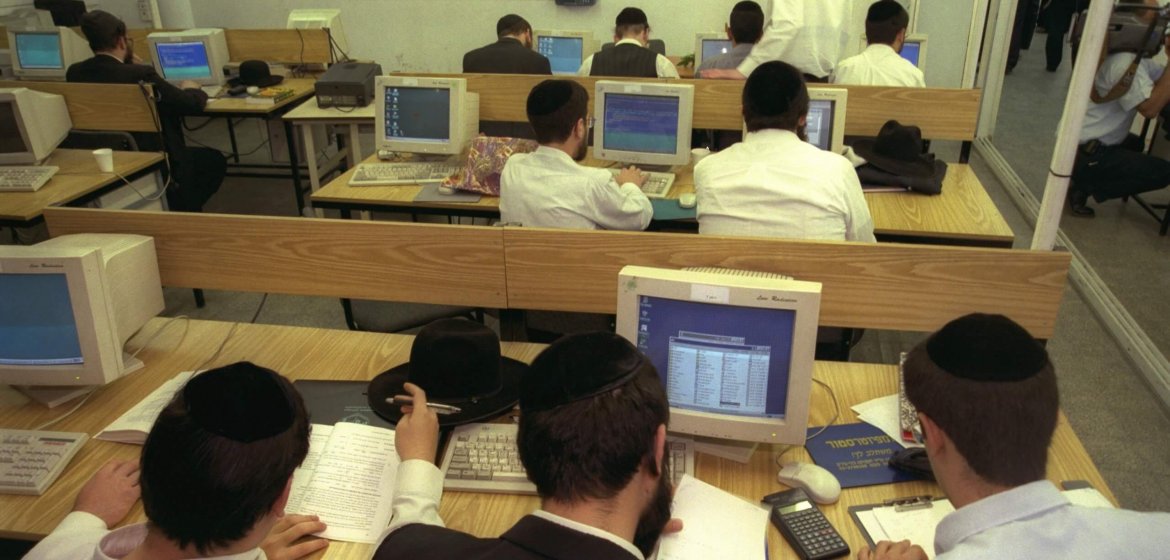

Picture credit: OHAYON AVI, La’am

If the world was unredeemable vanity, what would be our purpose in it at all? To whom here other than ourselves could our display of Torah learning, attachment to HaShem, goodness, and contentment matter?

So, while we can and should disrespect the surrounding culture’s sorry current state, we’re supposed to somehow influence those in it for good. HaShem did not tell Avraham that he and his descendants should live in a silo.

I suspect that working haredim spend more time learning Torah than most kollel avreichim. Surely no one with a scintilla of honesty would claim that most kollel men actually sit glued to their shtenders from morning to night “shteiging”. That is a priori ridiculous if only because the gray matter and sticktoitiveness needed to be a true lamdan are gifts as sparsely distributed as any talent — be it for music, or art, or physics. So who or what is responsible for this debacle of tens of thousands of meanderers posing as Bnei Torah? Perhaps it is the self-anointed gedolim and rebbes. We live in an era when both “chanoch lanaar al pi darko” and “asei lecha rav” are stood on their head. Rebbes and roshei yeshiva have a vested interest in controlling as many lives as possible if only to maintain and enhance their own status, if not to materially benefit themselves and their close famillies. It is in their personal interest to keep their minions as ignorant as possible, utterly dependent on their diktats, and hostage in a beit midrash so that there is no possibility of escape into a world where one must think for themselves and actually obey the mitzvah of “sheiset yamim taavod” without which Shabbat is effectively meaningless.

In the US the idea of being a “learner-earner” is a highly desired and praised option .

Nuance never was an easy sell but it’s become even harder in the current political climate

kt