Vladimir Zelensky, president of Ukraine since 2019, is the undisputed hero of the moment. Zelensky, who proudly heads Putin’s assassination list, has consistently refused out of hand every offer to evacuate him from Kyiv. “I need ammunition, not a ride,” he characteristically tweeted in response to the US offer to evacuate him to safety. His defiant, almost heroic stance against the might of Putin’s aggression has earned him universal admiration, and his powerful speeches tinged with dry humor have granted him iconic status. The Evening Standard dubbed him “the face of the free world,” and a Los Angeles Times op-ed penned by Alexander Motyl compared him to George Washington. Others have hailed him as “the modern Winston Churchill,” or even “leader of the free world.”

Zelensky’s meteoric rise from Ukrainian comedy actor to international hero is, of course, something quite outstanding. No less remarkable, in my eyes, is the fact that Zelesky is a Jew, the descendant of a standard Jewish family from Eastern (Russian-speaking) Ukraine that was decimated during the Holocaust. Aside from mentioning this as giving the lie to Putin’s claim of Ukrainian Nazism, Zelensky’s Jewishness has not attracted very much attention; I grant that there have generally been more pressing matters to discuss. Yet, I think it is worthy of some reflection: the Ukranian George Washington is a Jew. No less.

Zelensky’s Jewishness has not attracted very much attention; I grant that there have generally been more pressing matters to discuss. Yet, I think it is worthy of some reflection: the Ukranian George Washington is a Jew. No less

In the following lines I will try to offer some insights into Zelesky’s unique status as the most prominent Jewish leader for some time—perhaps since the time of Queen Esther. I mention Esther not merely because of the time of year, but also because I believe that drawing a comparison between the two—Zelensky as leader of Ukraine and Esther as queen of Persia—can be useful in sharpening some reflections on life in exile, life outside of exile, and the changing face of Jewish nationalism.

What’s the War All About?

The Russia-Ukraine war is a war about nationalism. Ukraine is a sovereign entity that finds itself—for whatever reasons—fighting a defensive campaign for its national survival. While there are many factors involved, the bottom line is that Russia is waging an imperialist war against the nation-state of Ukraine. Ukrainians, notwithstanding similarities, are not Russian, and their state possesses a distinct national identity that the Russian invasion threatens.

In a speech directed to the Russian people, just several hours before the military invasion began, Zelensky spoke the language of pure nationalism: “We are not part of one whole,” Zelensky said in his native Russian. “You cannot swallow us up. We are different. […] No one in Russia knows the meaning of these places, these streets, these names, these events. These are all alien to you, unfamiliar.” Zelensky proceeded to speak our “our land” and “our history,” of “our character,” “our people,” and “our principles.”

This, indeed, is the stuff that nationalism is made of: a shared territory, history, culture, language, character, and blood connection whether actual or imagined. But while there is not much that is novel in the substance of Zelensky’s speeches, there is much that is new in the context. His impassioned pleas have struck a chord with a world that seemed to have moved on from the golden era of the nation-state to an era of globalism, the European Union, and a disaffection with proud national identity—including, of course, that of Israel.

But Zelensky is not a prophet of every nationalism in the world. He is a Ukrainian nationalist and was elected to office, broadly speaking, on a platform of Ukrainian nationalism. For many of us, this raises a simple objection: surely Zelensky is Jewish?

Zelensky, whose speeches have garnered the support of world leaders and moved millions to tears—just watching his simultaneous translators choke up moves us to tears—has thus become the 21st Century prophet of European nationalism. He reminds us that Chesterton’s famous words remain contemporary: “Cosmopolitanism gives us one country, and it is good; nationalism gives us a hundred countries, and every one of them is the best.”

But Zelensky is not a prophet of every nationalism in the world. He is a Ukrainian nationalist and was elected to office, broadly speaking, on a platform of Ukrainian nationalism. For many of us, this raises a simple objection: surely Zelensky is Jewish?

Nationalism and Anti-Semitism

Many remember European nationalism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as the golden age of Europe. For Jews, the primary victims of the less pleasant aspects of European nationalism, the memory is far less bright. This is true for all Jews of Europe, but is certainly true if they happened to live in the territorial area now called “Ukraine.” The “new anti-Semitism” that flourished in Europe of the modern age was deeply informed by nationalism movements, which sparked hatred, harassment, attacks, and even murders of Jews, culminating of course in the Holocaust. Ukraine, as our collective memory knows well, is by no means an exception to this history. The common denominator of different national versions is pogroms, cruel killings, and intense anti-Semitism.

Khmenlnytsky, it is worth remembering, remains a Ukrainian national hero until today; a city and a large geographical area are named after him, his picture appears on the national currency, medals in his name are presented as one of the highest military honors, and his honored bust stands proudly at the center of Kyiv

The massacres of the Khmelnytsky Uprising of the mid-seventeenth century, during which tens of thousands of Jews were brutally murdered, are but one example of how Jews suffered the brunt of the rising Ukrainian national spirit. Khmenlnytsky, it is worth remembering, remains a Ukrainian national hero until today; a city and a large geographical area are named after him, his picture appears on the national currency, medals in his name are presented as one of the highest military honors, and his honored bust stands proudly at the center of Kyiv. His murderous legacy and his declared intention to cleanse Ukraine of its Jewish population do not tarnish his standing. Tens of thousands of Jews (at the very least) were again massacred during the premiership of another Ukrainian national hero, Symon Petliura; his direct or indirect responsibility for the pogroms during the Ukrainian Revolution period (the civil war of 1919-1921) remains a subject of discussion.

Against this violent backdrop, the Zelensky phenomenon requires serious scrutiny. In the heyday of European nationalism, it would have been unspeakable for a Jew to serve as head of state. Notwithstanding their formal emancipation and their intense efforts to integrate into the local population, local hatred of Jews never abated, and they were consistently rejected as a body rejects a foreign object. The tragic tale of German Jewry in the nineteenth and twentieth century, masterfully told by Alon Harel in his “The Pity Of It All,” sums up the Jewish relationship with their nation-state hosts—a one-sided relationship of Jewish love and German hate. As the Hebrew version of the title puts it, the entire story is a “German Requiem.”

Walter Rathenau was appointed as foreign minister of Germany because of his unique skills in the “art of the deal,” and certainly not because of German popularity. He was murdered in 1922 just several months after his appointment. Zelensky, in the starkest contrast, was elected into office by an overwhelming majority of Ukrainians and enjoys stable support, the more so after his unqualified endorsement of Ukrainian nationalism—an endorsement that did nothing to save the Jews of Europe just a few decades ago. Thus we find Zelensky, a non-apologetic Jew, rising to the status of Ukrainian national hero and handing out medals of the order of Bogdan Khmelnytsky.

What is going on here?

Jews Outside the State of Israel

I would like to highlight two fundamental changes that have allowed the current situation to arise. One of them relates to the form of today’s nationalism. From inception, tension was present between the nationalist tendency and the democratic order of Europe’s nation-states. But while in pre-war Europe democracy gave way before nationalist sentiment—Germany is the prime, but certainly not the only example—today it seems that the balance has shifted: the stronger democratic nature of today’s Europe seems to have mitigated the intensity of its nationalist sentiment. In the new European environment, even Jews can join the club.

I wish, however, to focus attention on the second factor, which relates to changes within the Jewish People. In the past, before the establishment of the State of Israel, it was infinitely harder for a Jew to fully and sincerely detach himself from his Jewish identity and adopt a different national identity—German, Hungarian, Ukrainian, or any other—while remaining Jewish. The only true option was conversion. A Jew everywhere was a Jew to the same degree—and as a Jew, the gates of citizenship were closed to him. Even after the gates were formally opened, the emancipation of European Jews did not cure them of their foreignness. The disease was a terminal one.

“We must refuse everything to the Jews as a nation,” said French nobleman and lawmaker Clermont-Tonnerre in 1789, “and accord everything to Jews as individuals.” Clermont-Tonnerre was a progressive who fought for the individual rights of Jews, but only on the condition that they entirely repudiated their Jewish national identity and adopted the French one in its place:

We must withdraw recognition from their judges; they should only have our judges. We must refuse legal protection to the maintenance of the so-called laws of their Judaic organization; they should not be allowed to form in the state either a political body or an order. They must be citizens individually.

His colleagues, who were less generous toward the Jews, understood the simple fact that Judaism is not merely a religion or creed, but a nation. Jewish denial of nationality cannot be sincere. The case for emancipation that Clermont-Tonnerre raised was that “we cannot have a nation within a nation.” The case of his rivals, alongside regular anti-Semitic tropes, was that the Jews, in their exilic condition, would always be a nation within a nation.

Far from their homeland, families living outside of Israel can today quietly assimilate without any need for conversion to another religion, and become full citizens of their chosen countries

Today, it seems, things are different. Several decades after the establishment of the State of Israel, a Jew outside of Israel has become a special type of Jew—a diaspora Jew, living outside of his homeland. By contrast with the past, the denial of his national belonging is today sincere and convincing to a degree that was never before possible. Just as a family from England can emigrate to Ukraine and after a couple of generations become a Ukrainian family for every intent and purpose, so can a Jewish family. Far from their homeland, families living outside of Israel can today quietly assimilate, without any need for conversion to another religion, and become full citizens of their chosen countries.

This theory is not new. It was written over one hundred years ago by none other than Theodore Herzl, who claimed that the proposed Jewish State would allow those so disposed to assimilate “to the very depth of their souls”:

The movement towards the organization of the state I am proposing would, of course, harm Jewish Frenchmen no more than it would harm the “assimilated” of other countries. It would, on the contrary, be distinctly to their advantage. For they would no longer be disturbed in their “chromatic fashion” as Darwin puts it, but would be able to assimilate in peace, because the present anti-Semitism would have been stopped forever. They would certainly be credited with being assimilated to the very depths of their souls, if they stayed where they were after the new Jewish State, with its superior institutions, had become a reality.[1]

This is precisely the story of Zelensky. While never denying his Jewish roots, his national belonging is of course entirely Ukrainian. And if in the past nationals would not accept Jews into their local club, today the gates of citizenship are open wide, just as they are open to immigrants from other countries with similar conditions. As with all recently arrived émigrés, questions of dual loyalties can always arise; but insofar as such suspicions can be set aside, which is certainly the case for Zelensky, there is no reason why Jews should not be accepted as a fully-fledged citizens of any nation-state of his choice.

Of course, none of this is to say that the stain of anti-Semitism has been cleansed from the global slate. Plenty remains. Anti-Semites on the radical Right continue to see Jews are insufferable and incurable cosmopolitans whose presence undermines the national character and its unique virtues. And anti-Semites on the Left, the “new anti-Semitism” of our current era, see Jews generally and the State of Israel in particular as a threat to the world order they wish to establish, the Palestinian issue being but one expression of many. Yet, these phenomena of Jew-hatred are irrelevant for Zelensky, whose Judaism has never hampered him from becoming a Ukrainian national hero.

Based on the foregoing analysis, I wish now to make a comparison between Zelensky and another Jewish figure that achieved political prominence in the diaspora: Queen Esther.

Which Nationalism? Esther Versus Zelensky

At the center of Megillat Esther, and most specifically of Esther’s own tale, stands the matter of Jewish national identity in a period of exile. In their exilic state, the Jews were considered a foreign body within the Persian Empire, which Haman, to whom Chazal attribute an especially evil tongue, expressed with great eloquence:

Then Haman said to King Achshverosh: “There is a certain people scattered and dispersed among the peoples in all the provinces of your kingdom. Their customs are different from those of all other people, and they do not obey the king’s laws; it is not in the king’s best interest to suffer them.”

Achashveros, who was clearly unconcerned about the consequences of eradicating the Jews, quickly acquiesced to Haman’s request. The non-Jewish population itself, as the wars at the end of the Megillah indicate, was also quite ready to implement the evil decree.

Like in the case of Nazi Germany, it seems that the planned genocide of the Jews came against a backdrop of nationalist assimilation. In their exilic condition, the Jews had started to lose their Jewish national identity; they had become Persians. This was the sin, alluded to in the Megillah and made explicit by the Sages, of having “derived benefit from the banquet of that evildoer” (Megillah 12a). Caving into external pressure, the Jews had adopted the local culture, and their national identity was slowly being eroded.

Fittingly, the only biblical character to be presented with two names, one Jewish and one non-Jewish is Esther: her Jewish name was Hadassah, while her given name is Esther (2:7)—the morning star in Persian (and also the Persian name of a goddess). By contrast with Mordechai, the Megillah presents Esther without any yichus (genealogy), telling us only that she had no father and mother. It was perhaps due to her weakened Jewish identity that Esther was able to conceal her Jewish roots while in the royal palace—a feat that would surely have been impossible for somebody with a deep Jewish identity and culture.

The end of the tale, of course, is a reawakening of Jewish national spirit on account of Esther’s self-sacrifice when called upon to “come before the king and implore him on behalf of her people” (4:8). Initially, Esther evades the calling on account of personal danger. As the Persian “first lady,” Esther had strayed from her Jewish roots; she was a Persian among Persians. Mordechai begs her to act on behalf of her nation, but she distinguishes between her personal fate and that of the Jewish People. She fails to understand why she should risk her life on their behalf.

Mordechai’s answer is that Esther remains a Jew, her fate inextricably bound with that of her nation: “Do not imagine in your heart that because you are in the king’s palace you alone will escape the fate of all the Jews” (4:13). He explains that her presence in the king’s palace will not save her from among the Jews, for even within the palace she remains part of the nation, and its fate is her own. Her elevated Persian status will not save her.

Moreover, Mordechai continues on to the next level: “For if you remain completely silent at this time, relief and deliverance will arise for the Jews from another place, but you and your father’s house will perish” (4:14). The covenant between God and the Jewish People is eternal, and it will ultimately ensure their national survival, though the course of survival remains unknown. Mordechai informed Esther that should she refrain from doing everything in her power for the sake of her own people, adopting instead the ostensible safety of her Persian identity, then she herself will stop enjoying the special protection afforded to the Jews. Rather than touch eternity, she and her father’s house—a reference to Esther’s lineage that the Megillah refrained thus far from mentioning (all we know is that she had no father and mother)—will terminate.

Esther found herself in the same situation. She knew full well that her children will be princes of Persia and will not grow up Jewish; she had no continuity among the Jewish People, and she therefore felt no obligation to risk her life for their sake

Mordechai’s response to Esther is similar to the Divine response to the eunuchs—those who ostensibly have no continuity within the Jewish People, and who lay a simple claim before God: “I am only a dry tree” (Yeshayahu 56:3). Hashem’s response is that they, too, have continuity: “For this is what Hashem says: To the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths, who choose what I desire and hold fast to my covenant—I shall give them within my temple and its walls a memorial and a name (Yad Va’Shem), better than sons and daughters; I will give them an everlasting name that will endure forever” (Yeshayahu 56:4-5). Esther found herself in the same situation. She knew full well that her children will be princes of Persia and will not grow up Jewish; she had no continuity among the Jewish People, and she thus felt no obligation to risk her life for their sake. Mordechai answered that even if her children will be lost to the Jews, her actions for the sake of the covenant will stand forever, granting her and her family “an everlasting name.”

Mordechai thus ends his statement with the words “And who knows if for this time you achieved royalty” (4:14). Mordechai informed Esther that her transformation into a Persian queen is not a loss of Jewish identity, but on the contrary, an opportunity to act within the framework of the covenant and save the Jewish People. Having internalized the message, Esther’s first action is to strengthen the national consciousness of the people, which is expressed in identification with Esther and prayer to God. She asks the people to fast on her behalf—for she has become their representative in the palace.

When Esther begs Achashverosh to save the Jews, she is thus careful to include herself with the people: “For we have been sold, me and my people, to be destroyed, to be killed and to be eradicated.” (7:4). Esther knew that she had other options; in the natural order of things, she was surely not endangered by the decree; yet, she includes herself with her people: “If I have found favor in your sight, O king, and if it pleases the king, let my life be given me at my petition, and my people at my request” (7:3). Her words, aside from pulling at Achashverosh’s heartstrings, are entirely sincere: her fate is tied to the fate of her people. Later, she continues to plea in the same vein: “For how can I endure to see the evil that will come to my people? Or how can I endure to see the destruction of my countrymen?” (8:6).

The story of Esther is the story of the Jewish People in their exile—a story in which the Name of Hashem goes unmentioned, in keeping with the Divine concealment inherent to the Jewish exile. The tale begins with a weakened Jewish identity and the dual threat of assimilation and eradication and ends with Esther’s heroic self-sacrifice on behalf of her people and their ultimate salvation. This is our collective story. Throughout the long years of exile, in all its variants, we had to withstand the harsh trial of loss of identity and belonging, yet we succeeded—with the help of the hidden God—to survive.

The tale begins with a weakened Jewish identity and the dual threat of assimilation and eradication, and ends with Esther’s heroic self-sacrifice on behalf of her people and their ultimate salvation. This is our collective story

President Zelensky, though a wonderful hero of Ukraine and perhaps even of the “free world,” presents us with a mirror image of Esther. In Esther’s exilic condition, revealing her Jewish identity would have fatally compromised her position in the palace, which is the simplest explanation for why Mordechai instructed her to keep it secret. By contrast, in today’s world Zelensky can be declaratively Jewish without this impacting his Ukrainian standing. Yet, the reason for this is that Zelensky’s Jewish identity is an empty set. He Judaism lacks expression in actions, in marriage (Zelensky’s wife is not Jewish), and in national identity.

By means of her courage and valor, Esther becomes the hero of the Jewish People. Zelensky, in these very days, is becoming a great hero of Ukraine. In the depth of exile, Esther, who the Talmud compares to the coming light of dawn, was able to awaken the latent force of Jewish nationalism. Zelensky, at a time when the Jewish exile is fading away, is also stirring a nationalism that has been dormant for some time—only that it is not a Jewish one. And for our purposes, that makes all the difference.

Jews and the Problem of Dual Loyalty

The year 1840 saw the return of the “blood libel” to the front pages of world history. Father Thomas, an Italian monk belonging to a Franciscan Capuchin friar and his Muslim servant disappeared in Damascus. Soon after their disappearance, the Jewish community was accused by the Christians of murdering Thomas and his servant and to have extracted their blood as part of the matzah-baking ritual. Under torture, a confession was extracted from a Jewish barber who told the persecutors that he, together with seven other notable Jewish men, had killed Thomas on the night of his disappearance. The other men were barbarically tortured, too, leading some of them to confess and others to die during their interrogation. The Christians were supported in their accusation by the French consul at Damascus, Ulysse de Ratti-Menton, leading French prime minister Adolphe Thiers to likewise blame the Jews.

The situation placed French Jewry in a conundrum. As French citizens, it was incumbent on them to support French interests in the Middle East; but as Jews, they could not remain indifferent before France’s support of an abominable crime against their own people. Ultimately, the involvement of Sir Moses Montefiore and French politician Adolphe Crémieux led to the release of the Jewish prisoners and the end of the sordid affair—but not without a significant price tag:

The outcome was an apparent victory in humanitarian terms but, as Lindemann shows, it was a Pyrrhic one. Thereafter, French patriots argued that the love of their brethren would always be greater than the love of French Jews for France. Jews would always be Jews. […] It was but a small step to convincing fellow patriots that Jews were part of an omnipotent global conspiracy. Such a widely held perception was later to fuel nineteenth- and twentieth-century anti-Semitism.[2]

The Damascus Affair serves as a worthy example of the “dual loyalty” problem that has plagued diaspora Jews for centuries and was recently raised in the context of the Jewish spy Jonathan Pollard. In an interview with the Yisrael Hayom daily, Pollard described how American Jews refused to support him (though the position softened over the years), claiming that he was disloyal to his state. Pollard’s response was that his allegiance was to the Jews:

Their attitude was, “Get the hell out of our face. You already showed where your loyalty was.” And I always have an argument with these people. I said my loyalty is to the Jewish people and the Jewish state. And they said, “Well, you don’t belong here.” I said, “Barur [obviously].” “I don’t belong here,” I said, “neither do you. You should go home.” Their answer was, “We are home. This isn’t exile, this is the United States.”[3]

It is worth noting that the United States is, as a country of immigrants established around an idea rather than an ethnic nationality, is a more complex case—hence the appeal of the claim that “this isn’t exile, this is the United States.” Concerning European nation-states, the contradiction between Jewish belonging and local nationalism and the concomitant problem of dual loyalty is all the sharper.

These diaspora issues derive from the core idea that Judaism is a “nation” even before it is a “religion.” More precisely, we are a nation defined as a people living within a relationship with Hashem. “Your people are my people, and your God is my God,” said Ruth to Naomi as she approach her to join the Jewish People. It is not possible to disconnect the two. From the days of Avraham Avinu, and all the more after our national birth from Egyptian bondage, our national belonging and our religious essence are one. “This nation I have created for Myself—My glory they shall tell” (Yeshayahu 43:21).

Judaism cannot be a religious calling alone, a set of faith principles and actions outside of a concrete national context

On the one hand, being Jewish cannot be condensed into national belonging bereft of religious and theological meaning. Rabbi Uriel Zimmer was thus correct in his critique of certain Zionist leaders, for whom Jewish action started and ended with contributing to the Jewish national project, irrespective of religious faith and action: “The novelty that Zionism brought to the world was a change in the definition of being Jewish; from the giving of the Torah at Sinai until Zionism the definition was Torah, while from now on the definition is nationalism, nation belonging.”[4]

On the other hand, Judaism cannot be a religious calling alone, a set of faith principles and actions outside of a concrete national context. In this matter, perhaps the clearest articulation is that of Rabbi Shmuel Glasner, who fiercely critiques some of his Charedi brethren, who declared for political reasons that they were Hungarians like all others, only belonging to the Jewish faith. In doing so, Rabbi Glasner argues, they “join forces in this with the assimilators”—the Hungarian Reform movement that took a similar position.[5] Rabbi Glasner argues that formal Orthodoxy has chosen “to adopt the reprehensible lie that Jews are but a separate religious community”—as though Jews can truly be “Hungarians of the Mosaic religion.” Such a declaration, he states, “is considered as outright heresy, and it is forbidden with the force of yehareg ve-al ya’avor [rather be killed than violate].” In the Hungarian context, “it shall remain in the annals of Israel as a shameful stain, never to be erased, on Hungarian Orthodoxy.”

Leaving aside the particular dispute over which pragmatic measures are permitted, and which are not, the outtake is that a Jew cannot be entirely Italian, entirely Spanish, or entirely Ukrainian. These can certainly comprise a secondary identity and be significant in terms of character and culture, but the primary identity of a Jew is simply “Jewish.” Today, at a time when the Jewish People are fortunate, by the grace of God, to enjoy political representation in the form of a sovereign Jewish state, this identity inevitably translates into allegiance to the State of Israel. In turn, this inherent loyalty precludes, at the very least for an ethnic nation-state, the possibility of a Jew serving as head of state for a country other than Israel.

Esther herself teaches us that issues of “dual loyalty” can be overcome by seeking the joint interest of both parties

To clarify: I do not mean to argue that a Jew living outside of Israel cannot be loyal to his host country. Of course, he or she can and must exercise good citizenship in their host country; there is no reason why a person should not be in possession of dual citizenship, Jewish and Italian, so long as the relevant country is not hostile to Jews and their state. This is true of the vast majority of cases, and even of somebody who holds a government office of one sort or another. Esther herself teaches us that issues of “dual loyalty” can be overcome by seeking the joint interest of both parties: her action on behalf of the Jews was not to the detriment of the Persian Empire, and on the contrary, the Megillah indicates that Achashverosh’s kingdom flourished under the influence of Mordechai and Esther, to the degree that he was able to collect greater income in taxes (10:1).

However, there can come a point at which an unresolvable tension arises, at which time the diaspora Jew will have to make a decision: resign from all relevant positions or responsibilities, or relinquish “Jewish citizenship.” Esther, when she was called upon to act for her people, was ready to do so even at the cost of likely death. Zelensky, in becoming president of Ukraine and binding himself absolutely and unequivocally to the Ukrainian interest—effectively resigned his place among the Jewish People.

The Time of Jewish Nationalism

Last week I was asked if it would be right for an Israeli Jew currently in Ukraine to volunteer for service in the Ukrainian forces fighting against Putin’s invading armies. President Zelensky has announced that thousands of non-Ukrainians have joined the war against Russia, and the questioner thought that perhaps this would be the moral thing to do, joining the forces of right and light against those of evil and despotism. My answer, while certainly identifying with the question, was that this would not be appropriate. The article above is an explanation of why.

The halacha does not formally forbid serving in a foreign army—though there is room to discuss this from the perspective of placing oneself in danger. Yet, by the same token, there was no halachic prohibition against deriving benefit from the feast of Achashverosh. The problem was not halachic, in the narrow sense, but rather national—an issue of Jewish identity. Our connection with Hashem cannot be maintained as individuals, but only as a nation. And if in the past our exilic condition narrowed the scope of the expression and realization of this national belonging, today, in the age of the Jewish State, the national aspect of being Jewish has returned to center stage in our Jewish experience. This is true irrespective of the level of our support or lack thereof of the State of Israel. It is, I believe, an undeniable fact of modern Jewish living.

Why, indeed, should a Jew who is faithful to his own people sacrifice his life for the war of a foreign nation?

Volunteering for a foreign army, which is literally matter of life and death, is akin (for our purposes) to serving as head of a foreign state. Ukraine is fighting its war of national independence. Even if our hearts go out to them for humanitarian reasons, or even for reasons of right and justice, our first allegiance must be to our own nation and not to a foreign people. In matters of war, of risking one’s very life, this loyalty is decisive; each person only has one life to risk. The State of Israel needs its soldiers to bravely defend the Jewish People in their homeland. Even in Ukraine and neighboring countries, there is much work to be done on behalf of Jewish brethren in distress. These projects take precedence. Why, indeed, should a Jew who is faithful to his own people sacrifice his life for the war of a foreign nation?

***

Some of us have the incredible merit of living in our ancestral homeland, under the Jewish sovereignty of the State of Israel. Some of us don’t. Either way, it is crucial to recall that being Jewish is living a national connection to Hashem rather than a personal one. Or, perhaps more precisely, our personal connection with Hashem derives from our belonging to the Jewish People. Judaism cannot be constrained to the private dimension of our lives, for its basic definition is the connection between a nation, an entire people, and Hashem. Our duty of allegiance to the Jewish People is emphasized in the story of Esther, the mirror image of President Zelensky who has become a Ukrainian hero at the expense of his Jewish belonging. Today, in the era of the return of Jewish nationalism, this duty is more relevant than ever.

“Be strong, and let us be strengthened for the sake of our people and the cities of our God; and Hashem will do what is good in his eyes” (II Shmuel 10:12).

[1] Theodore Herzl, The Jewish State (1917), p.4; I am deeply indebted to Rabbi Gamliel Shmalo for bringing this source to my attention after reading an earlier version of the article.

[2] Cohen, Robin. 1996. “Diasporas and the Nation-State: From Victims to Challengers.” International Affairs 72 (3): 507-22, p. 510.

[3] Boaz Bismuth, Caroline B. Glick, and Ariel Kahana, “American Jewry consider themselves more American than they do Jews” Yisrael Hayom (3.25.2021); available at https://www.israelhayom.com/2021/03/25/american-jewry-consider-themselves-more-american-than-they-do-jews/.

[4] Uriel Zimmer, Yahadut Ha-Torah Ve’ha-Medinah (Brooklyn, 1959).

[5] R. Shmuel Glasner, “Zionism in the Light of Faith,” S. Federbush, Torah u-Meluhah (Jerusalem, 1961).

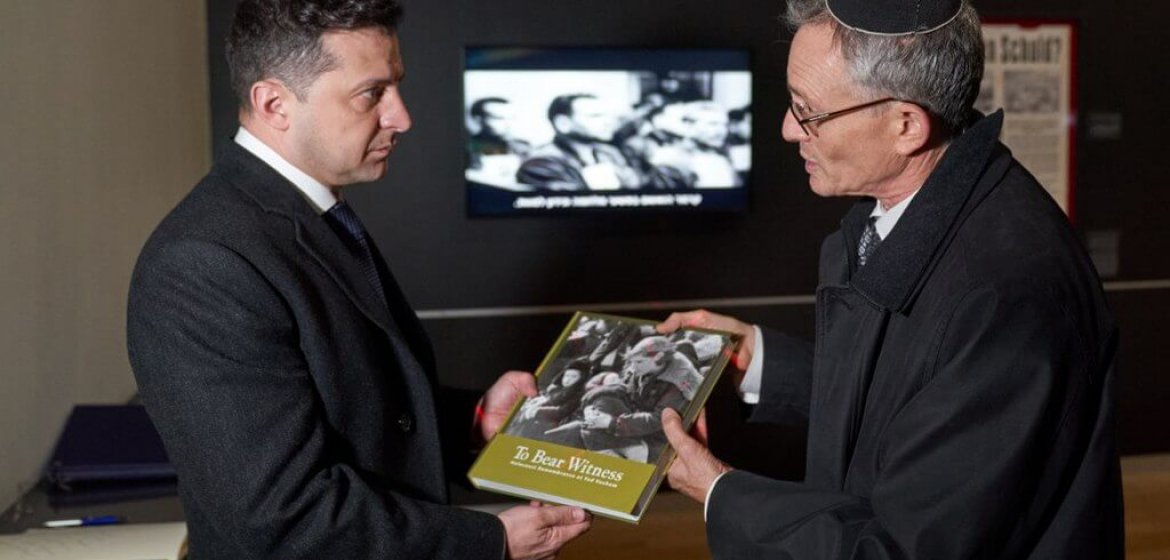

Photo by Kmu.gov.ua, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

our first allegiance must be to our own nation and not to a foreign people.

=======================

Agreed, but some might say stopping the aggression there is an investment in making sure it doesn’t reach here. IIRC correctly the zion mule corps was a similar investment

KT

Speaking of Esther and Persia—

US Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer has a shot at some Esther-like moments with respect to the impending, calamitous Iran deal. Will anything or anyone motivate him to step up in open opposition as a leader, not just as an individual? Specifically, will Jewish organizations who support Israel or its Jews step up to motivate him? On a normal day, they fawn over him to get certain appropriations passed or favors granted. A lot may depend on the result. Activating liberal Schumer won’t be easy; Biden is trying to give the Senate an out by (illegally) not offering this treaty for a vote at all. Schumer values his Senate position, but above his people?

Very thoughtful and insightful article, thank you so much!

May I please understand why Putin is being posed so one-sidedly negatively? Why state so confidently that he lied? Maybe it’s the West (and by extension its Jewish population) who’s being lied to by Zelensky who is a very extraordinary con artist?

Every conflict has two sides, however the Russian side is being forcefully silenced and totally delegitimised in the West. I struggle to understand your taking on only the side of the story repeatedly parroted in the West. Such a de javu vis a vis the Israeli Palestinian conflict, isn’t it?

West does not equal good, same as East does not equal evil. Zelensky is a war criminal who made of a nation of 44,000,000 people into a pawn between the West and the East. His people are deliberately used as human shields in crowdly populated areas (think Hammas). Once the war finishes, realistically the population in Ukraine will be reduced by 25 to 50 per cent. And who would be blamed? Of course, the Jew Zelensky, who can at any moment leave with his family to Israel and become Israeli citizens, whilst the simple Ukrainians are still reeling from the war.

My father, z”l, fought with the US. Army in France during WWII. Are you saying he should have not done so?

A few fundamental differences, I think:

1. Jews were of course the primary victims of WWII, so any Jew fighting against the Nazis was fighting his own war.

2. WWII was not about any specific nationalism, but a global war of good against evil. It is honorable to join such a war.

3. Victory against the Nazis enabled the establishment of Israel; the Grand Mufti, as we know, was an ally of Hitler.

We certainly take pride in some 1.5 million Jews who served in the allied forces in WWII. Should not be conflated with the point of the artice.

Contains thoughtful ideas.