Distinguishing between the written Torah (the Tanach) and the Oral Torah (the Mishnah and Talmud) was a fundamental element of one Zionism stream. According to this perspective, known for its influence on Ben Gurion, the Tanach represents a nationalist approach distinct from the “exilic” Judaism of the Sages. This Zionist stream sees itself as aspiring to return to a “Tanachic” Judaism and dismisses Charedi Judaism, accordingly, as one that adheres specifically to the Judaism of the Sages.[1]

In contrast, the Talmudic tradition rejects any suggestion of fundamental distinctions in approach between the Tanach and Chazal, seeing itself as the authoritative interpreter of the Torah and the prophets. However, this does not mean that the Sages did not recognize differences between the Tanach period and their own time.

Certainly, they acknowledged linguistic variances between scripture, the writings of the scribes, and that of later sages. In the days of Ezra and the Great Assembly, Judaism underwent a significant transformation, which the Sages note in highlighting the abolition of the desire for idol worship, the cessation of prophecy, changes in the Hebrew script, the creation of protective measures for the Torah, and the establishment of prayers and blessings. The Rishonim wrote about the theology of reward and punishment, directed toward our earthly reality during the Tanach period and redirected at the World to Come by the Sages. Distinctions are also drawn between the spiritual condition during the First Temple era and after the Destruction, and so on.

The Rishonim wrote about the theology of reward and punishment, directed toward our earthly reality during the Tanach period and redirected at the World to Come by the Sages

Though the Talmudic Sages paint a general picture of spiritual decline over the historical timeline, one Midrash presents the Sages and the prophets as being on the same level, as though they were two rival schools, with the difference between them framed in terms of “new” versus “old” rather than superior versus poor: “Moshe’s cohort, Yehoshua’s cohort, and David and Chizkiah’s cohorts—these are old. Ezra and Hillel’s cohorts, and those of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, Rabbi Meir, and his colleagues—these are new. Of them, it is said: ‘Both the new and the old.’”[2]

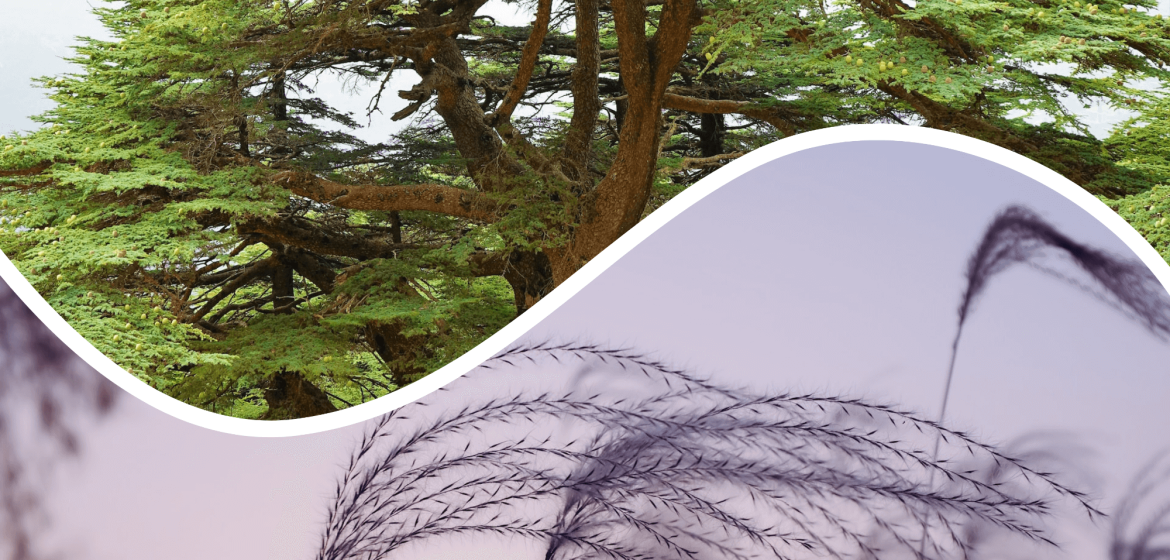

In the following lines, I would like to focus on one motif of the distinction between the old and the new, which holds profound practical significance for our present days: the competing interpretations concerning the clash between the reed and the cedar.

Reed or Cedar? Between Scripture and the Sages

The Tanach mentions the cedar tree seventy-three times, more than any other tree, portraying it as the king among trees. Yechezkel is particularly expressive of the cedar’s impressive stature: “Behold Assyria, a cedar in Lebanon with beautiful branches and a shady thickness, tall of stature, with its crown among the thick branches […] no tree in God’s garden could compare to it in its beauty” (Yechezkel 31:3-8). Scripture often likens high-standing individuals to the cedar, famous examples being “the righteous bloom like a date-palm; they thrive like a cedar in Lebanon”; “a righteous man will flourish like a date palm, like a cedar in Lebanon he will grow tall.” The righteous of scripture are Lebanon cedars.

The reed, on the other hand, is mentioned in Tanach in a negative context. The splintered cane expresses weakness and instability, and it is used by the prophets as a metaphor for powerlessness and incompetence. In this way, the prophet Achiyah foresaw the fall of the kingdom of Israel: “For Hashem will smite Israel as a reed lurches about in the water, and He will uproot Israel from upon this bountiful land that He gave to their forefathers, and He will scatter them beyond the [Euphrates] river” (Melachim 1 14:15). In another instance, the prophet likens Egypt to “the support of this splintered reed”—which cannot be relied upon (Yeshayah 36:6).

Surprisingly, Rabbinic literature entirely reverses the roles: the reed symbolizes a positive attribute that one should aspire to, while the cedar is a negative symbol, something that should not be emulated:[3]

Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani says in the name of Rabbi Yonatan: What is the meaning of that which is written: “Faithful are the wounds of a friend; but the kisses of an enemy are importunate” (Mishlei 27:6)? Better is the curse that Ahijah the Shilonite cursed the Jewish people than the blessing that Bilam the wicked blessed them. Achiyah the Shilonite cursed Israel with a reed, as it is stated: “For Hashem shall smite Israel as a reed is shaken in water” (I Melachim 14:15). There is an aspect of blessing in that curse, as he was saying they will be just like a reed that stands in a place near water, as the water sustains it, and its stalk replenishes itself, as if it is cut another grows, and its roots are numerous. And even if all the winds in the world come and gust against it, they do not move it from its place and uproot it. Rather, it goes and comes with the winds. And once the winds subside, the reed remains in its place. But Bilam the wicked blessed them with a cedar. There is an aspect of curse in that blessing, as he was saying they will be just like a cedar that does not stand in a place near water, and its roots are few relative to its height, and its trunk does not replenish itself, as if it is cut it does not grow back. And even if all the winds in the world come and gust against it, they do not move it from its place and uproot it. But once a southern wind gusts, it immediately uproots the cedar and overturns it. Moreover, the reed was privileged to have a quill [kulmos] taken from it to write scrolls of Torah, Prophets, and Writings. Therefore, the curse of Achiyah is better than the blessing of Bilam” (Sanhedrin 105b-106a).

Reeds, in short, are resilient and durable, almost irrepressible. Nothing can uproot them. The cedar, by contrast, is vulnerable to multiple threats, and its ostensible blessing is nothing other than a curse.

Rabbinic literature reverses the interpretation. The weakness of the reed becomes a symbol of timeless eternity, something that cannot be destroyed by force, like the letters of the Torah or the Jewish spirit that cannot be displaced even by the strongest wind

Avot de-Rabbi Natan (Chapter 41) makes the contrast even sharper, presenting the reed as a symbol of endurance, a tool for writing the eternal Torah, unlike the temporary and transient nature of the cedar, which serves as firewood:

A person should always be as soft as a reed and not rigid as a cedar. For the reed, when all the winds come and blow against it, moves in their direction. But when the winds quiet down, the reed returns to its place. That is why the reed merited to be made into a quill that is used to write a Torah scroll. But the cedar does not stay in its place; when the southern wind comes and blows against it, it uproots the tree and flips it over. And then what happens to the cedar? [Woodcutters come along and chop it up, and take from it to build houses and then] throw the rest into the fire. And that is why they say: A person should always be soft like a reed and not rigid like a cedar.

The interesting point in this disparity is that the symbolic meanings of the reed and the cedar in Tanach and Rabbinic literature are the same. In both, the cedar is a symbol of strength and attachment to its unmoving roots, while the reed is a symbol of mobility and flexibility. Moreover, the key to judging their respective qualities is identical: the yardstick for measuring their worth is stability versus transience. Despite this, the Sages assign a negative view to the cedar and a positive one to the reed, a direct contradiction to the Scriptural view.

In Scripture, the cedar symbolizes permanence and eternal stability—the House of Cedar built by Shlomo stands in contrast to the temporary tent that housed the Mishkan, the splintered reed in contrast to the elevated cedar. However, Rabbinic literature reverses the interpretation. The weakness of the reed becomes a symbol of timeless eternity, something that cannot be destroyed by force, like the letters of the Torah or the Jewish spirit that cannot be displaced even by the strongest wind. The might of the cedar, by contrast, is judged harshly as a superficial strength that can be swiftly destroyed.

From Power to Spirit

The shift in values from strength to adaptability is not a marginal change. The physical power of the cedar—its height, strength, and stability, which symbolize the people’s strength and strong connection to their land—is given a wholly different evaluation by the prophets and the Sages. The Sages elevate the advantage of the diaspora Jew, who may lack the strength to stand and defend himself, but much as the reed, can bend beneath the turbulent wave of the moment and raise his head elsewhere. While weak and seemingly fragile, his adaptability, which prevents him from building permanent houses and fortresses, ensures his survival.

The sages replaced the righteous person of the Tanach, symbolized by the cedar, with the righteous exilic Jew who may bend like a reed over his Talmudic lectern but whose soul remains upright and stable, like an eternal candle swaying in the wind

Furthermore, the reed’s existence is not earthly but spiritual. The sages replaced the righteous person of the Tanach, symbolized by the cedar, with the righteous exilic Jew who may bend like a reed over his Talmudic lectern but whose soul remains upright and stable, like an eternal candle swaying in the wind. The sanctuary and homeland of this righteous Jew are the spiritual realms of the study hall, and the strength of the cedar is replaced by the soft murmuring of Talmudic discourse—the recitation of Torah and its fiery letters floating in the air.

This Talmudic perspective, which shaped Judaism in its current form, is explicitly expressed in its persistently negative attitude toward the cedar. The cedar is the imagery of Esav’s hands (no less), symbolizing gentile aggression: “He does not rule over them except with cedars.”[4] This is also evident in the description of Egyptian slavery, in which the subjugating enemy is likened to the cedar, while Israel is the feeble worm that gnaws at the wood:

It says: Fear not, you worm Yaakov (Yeshayahu 41:14). Why is Israel compared to a worm? To teach us that just as a worm has only a soft and tender mouth to strike at a hard cedar tree, so Israel has only its prayers. Idolaters are likened to a cedar, as Scripture states: Behold, the Assyrian was a cedar in Lebanon (Shemos 31:3). And Hashem breaks in pieces the cedars in Lebanon (Tehillim 29:5).[5]

Similarly, in the Midrash concerning Haman’s decrees, the reed of Israel confronts the cedar of Haman:

The Sages said, Haman’s gallows were made from cedar, since Haman cast lots… He cast lots on the reed. The Holy One, blessed be He, said to him, “Foolish one! Israel is likened to a reed that stands in the water and moves with every wind and breeze. Even though the water is strong, the reed stands in its place, and they are not likened to a cedar that the wind smashes. However, the idolaters are likened to it, as it is said, “Behold, Assyria, a cedar in Lebanon” (Yechezkel 31:3). But as for Israel, it is written, “as a reed lurches about in the water” (I Melachim 14:15). Behold, the cedar has been prepared for you since the six days of creation, “on the gallows that He had prepared for him” (Esther 7:10).[6]

This may be also the meaning of the obscure Midrash that attributes the destruction of Beitar to “a shaft from a carriage.” According to the Midrash, the people of Beitar used to plant a cedar tree for every boy born in the city and make a canopy from it on his wedding day. As the Midrash recounts, Caesar’s daughter passed by the place one day, and a shaft from her carriage broke. To fix it, she cut down one of these cedar trees, and as a result, the people of Beitar attacked her. This attack triggered the destruction of Beitar (Gittin 57b).

In light of the above, perhaps the Midrash indicates that the insistence on the cedar symbolism represents a flaw of aliyah bechoma, an illegitimate attempt to restore political sovereignty by force, which ended in the tragedy of the destruction of Beitar. Similarly, our Sages recount that Bar Kochba sought to test his soldiers’ strength by uprooting a cedar tree from the forests of Lebanon.[7]

The Cedars and Reeds of Our Times

At the beginning of the article, I mentioned the connection between Zionism and a return to Scripture. This return is symbolically expressed in the cedar planted by Herzl during his visit to the land (the “Arza” resort, named after this cedar, is located near Jerusalem).[8]

Over the years, however, the enthusiasm for “returning to Tanach” weakened in Israeli society.[9] Societal transformations, especially since the 1970s, have brought the general population far closer to Jewish tradition shaped by the Talmudic Sages of the Talmud.[10] As former president Reuven Rivlin stated, “The negation of exile is the legacy of the past.”[11] Conversely, the Charedi public has not stagnated, and it is challenging to declare today that Charedim categorically reject Zionism, as might have been true in the past. The Charedi public is becoming increasingly nationalistic.

Against this backdrop, I believe that the horrific Simchat Torah events highlight with renewed intensity the question of the reed and the cedar both among the Zionist-Israeli public and amid Charedi society. The calamity of October 7 touched the exposed nerves of the Jewish consciousness that underlies Zionism and its attitude toward exile. On the one hand, they challenge the Zionist idea that the construction of a magnificent cedar structure will lead to a condition of “never again.”

Be’eri and Kishinev remain incomparable. In Kishinev, the Jewish reed, feeble and eminently vulnerable, had no choice but to lament the persecution, pack its belongings, and migrate across the sea. In Be’eri, the powerful cedar drew its bow and trampled the Palestinian worm that plagued it

Zionism criticized the exilic reed that defined the Jewish reaction to the Kishinev pogrom. Yet, even the protection of solid cedar wood was corroded by the arsenic in the mouth of Palestinian worms. On the other hand, Be’eri and Kishinev remain incomparable. In Kishinev, the Jewish reed, feeble and eminently vulnerable, had no choice but to lament the persecution, pack its belongings, and migrate across the sea. In Be’eri, the powerful cedar drew its bow and trampled the Palestinian worm that plagued it.

Critique of Zionist hubris is thus combined with an inspired return to the spirit of Zionist courage.

Erez Eshel and Rav Dov Landau

The collision between the conflicting ethea of the cedar and the reed was fully manifest in an encounter between the symbolically named army officer Erez (Cedar) Eshel and the great Talmudic scholar Rav Dov Landau.

Eshel, a colonel in the reserves and a prominent and charismatic educational entrepreneur, is among the last representatives of the Zionist ethos of exile negation. A meeting with Eshel, among the founders and leaders of Israel’s pre-military preparatory programs and a person who grew up in a religious-Zionist home, might seem like a throwback to the Shomer Hatzair movement of the 1950s. The discourse is likely to include a grandiose presentation of an exemplary society, a profound sense of national responsibility, a dedicated ethos of sovereign power, and a resolute declaration that the young boy in the old photo will never raise his hands in surrender again. This Zionist language that dominated Israel in the 1950s is barely heard today.

On the Simchat Torah of October 7, Eshel, of his own initiative, selected one of his elite Ein Prat students and traveled south to assess the situation. Under life-threatening fire, the two of them saved multiple lives (including several wounded by gunshot) and collected bodies from army bases and settlements. Upon his return from the inferno several days later (and before coming home), Eshel entered a range of Charedi Shuls and Yeshiva study halls, struck the ground with the barrel of his rifle, and demanded from his astounded audiences that gentle-hearted Yeshiva boys enlist in the IDF and defend their country. Reed, meet Cedar.

Faced with the towering cedar, which requested some reeds to make into shrouds for the dead or bandages for the wounded, Rav Dov rejected the appeal under the pretext that the sensitive souls of Yeshiva students, being as soft as reeds, would be injured

The ultimate clash between cedar and reed was captured in another encounter and articulated in a single sentence. After he visited the yeshiva institutions, Eshel traveled to Bnei Brak and lowered his tall, cedar-like figure before the elderly sage Rav Dov Landau—perhaps the most prominent representative of the “reed ethos” in our generation. Faced with the towering cedar, which requested some reeds to make into shrouds for the dead or bandages for the wounded, Rav Dov rejected the appeal under the pretext that the sensitive souls of Yeshiva students, being as soft as reeds, would be injured. Some will argue that Rav Dov wished to “rebuff him with a reed,” as the Talmudic expression goes. In any case, the moment brought to a head the cedar-reed tension that exploded on Simchat Torah morning.

I cannot tell, but perhaps we can hope that as we read in Yechezkel’s prophecy, Hashem will unite the trees and make them one:

I will make them into one nation in the land, upon the mountains of Israel, and one king will be a king for them all; they will no longer be two nations, and they will no longer be divided into two kingdoms, ever again. They will no longer be contaminated with their idols and with their abhorrent things and with all their sins. I will save them [taking them] from all their dwelling places in which they had sinned, and I will purify them; they will be a nation to Me, and I will be a God to them. My servant David will be king over them, and there will be one shepherd for all of them; they will follow My ordinances and keep My decrees and fulfill them. They will dwell on the land that I gave to My servant Yaakov, within which your fathers dwelled; they and their children and their children’s children will dwell upon it forever; and My servant David will be a leader for them forever. I will seal a covenant of peace with them; it will be an eternal covenant with them; and I will emplace them and increase them, and I will place My Sanctuary among them forever. My dwelling place will be among them; I will be a God to them and they will be a people to Me. Then the nations will know that I am Hashem Who sanctifies Israel, when My Sanctuary will be among them forever. (Yechezkel 37).

It is up to us to see the prophecy’s realization.

[1] See, for example: Amir Mashiach, ‘From those days to the present – Analysis of the character of the Jewish sectors in Israeli society today in light of ancient Jewish identities,’ Social Issues in Israel 17, pp. 68-38.

[2] Vayikra Rabbah 2:11. Also, compare Eruvin 21b: “It was related that Rav Ḥisda said to one of the Sages who would arrange the traditions of the aggada before him: Did you hear what the meaning of: New and old is? He said to him: These, the new, are the more lenient mitzvot, and these, the old, are the more stringent mitzvot. Rav Ḥisda said to him: This cannot be so, for was the Torah given on two separate occasions, i.e., were the more lenient and more stringent mitzvot given separately? Rather, the old are mitzvot from the Torah, and the new are from the Sages.”

[3] Yonah Frankel has already addressed this exchange between the cedar and the reed in the context of the Sages in the interpretation of the symbolism of the cedar and the reed in a parallel text in Ta’anit. However, the issue in Ta’anit is a question of interpretation, which is not relevant here. See The Tale of the Aggadah – Unity of Content and Form, HaKibbutz HaMeuhad, 2004, pp. 189-197. Rozenson also (in note ? above) mentioned the transformation of the cedar into a negative symbol.

[4] Mechilta d’Rebi Yishmael Beshalach – Masechta d’Shira Parsha 6.

[5] Midrash Tanchuma (Warsaw edition) Parshat Beshalach 14:10

[6] Yalkut Shimoni Esther Remez 1054

[7] Talmud Yerushalmi Tractate Ta’anit Chapter 4

[8] Various Aggadot have developed around this cedar, and in fact, it was not speaking about a cedar but about a cypress mistakenly identified as a cedar. See: https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%90%D7%A8%D7%96%D7%94.

[9] For further reading on this topic, see Anita Shapira, ‘The Tanach and Jewish Identity,’ Magnus, 5766, pp. 1-37.

[10] The subject has been extensively researched; see, for example: Ofer Schiff (editor) ‘Israeli exiles: homeland and exile in Israeli discourse,’ Ben-Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, 2015. Liat Shteyer-Livni, ‘The comeback of the exile: From an exilic Jew to a new Jew and back,’ in Liat Shetiyer-Livni, Adia Mendelson-Maoz, Sandra Hameiri, and Yael Munk (editors), Identities in the formation of Israeli society, Raanana: Open University Press, 2013, pp. 461-481. Anita Shapira, ‘Where is the “negation of the 2000 year exile” going?’ , 25 (5763). Ilan Gor-Ze’ev, Towards education for an exilic mentality: Multiculturalism, Post-Colonialism, and Counter-Education in the Post-Modern Era, Tel Aviv, 2004.

[11] President Reuven Rivlin: ‘The rejection of the exile is the legacy of the past’ | Channel 7 (https://www.inn.co.il/news/439450). Rivlin extensively references the matter, from the famous Tribes Speech to his “Statehood has disappeared from the Land.” Note that some responded in opposition to Rivlin’s negation of the exile. See, for example, Attorney Ron Tira’s response in Maariv, October 27, 2017, regarding Rivlin’s “door slamming on the diaspora.”

Just don’t understand why we are so happy about chareidim joining the army it’s not our role and you’re not fulfilling your tafkid which is to learn etc it’s terrible

This opposition is a little too simple. in reality there are many nuances and compromises possible. I think Erez as described here was not diplomatic. But the pretext or Rav Landau is also problematic. Only his Bachurim have a soft soul? In addition Kishinev was in Galut, they could wait the storm, (surviving or not) but there was hope for better times because it was local. Now we are in Eretz Israel and if we don’t defend ourselves, there is a real risk of annihilation of the whole people. So let’s work for the fulfilment of the prophecy, with dialogue and MUTUAL respect.

Perhaps Erez did not go about it in the most diplomatic way, but his point was very well taken. Why does one segment of the community almost completely avoid army service? In particular, we are living through a milchemet mitzvah, during which halacha dictates that all need to either fight or support the fighters. To argue that learning Torah is going to be our salvation is illusory. Without the IDF protecting the country, does anyone doubt that every Jew would be a target for murder, whatever his/her religious inclinations and practices? All the learning in the world never has and won’t, on its own, protect our people. In addition, what is this talk about “tender souls”? Is a hesder boy any less tender? Is a secular boy any less tender? It is time for the community to reject this type of thinking and assume the mantle of citizenship.

Dear David

There is an issue I see, where people speak to convince themselves and not those whose behavior they are attempting to change.

Your claim of milchemet mitzva is one that charedim may not accept, considering the various conditions for the halachic status.

We absolutely believe that living according to halacha protects us, and denigrating Torah study and claiming it does not protect is not helpful to your claims. You will not convince me or any devout haredi by simply asserting your (incorrect) beliefs.

As for tenderness, they are generally more tender – of course, this is a purposely cultivated state, and it is wrong to cultivate tenderness and use that to avoid supporting other jews.

A better version of your reply would have pointed out that there is NO exemption from war for scholars according to Jewish law, so clearly G-d believes that learning is not the main hishtadlut in war, and further pointed out that raising boys to be weak and so unable to support those risking their lives is incredibly inappropriate