Whether you support Charedi political parties or not, the phenomenon of Charedi votes seeping from their traditional ballot box into non-Charedi rightwing parties should make us pause and think. The matter, as the case for all major Charedi affairs, is relevant far beyond the borders of local Charedi politics.

The Charedi share of Israel’s adult population rises yearly, principally due to natural growth. Birthrates speak for themselves. Yet, not only has the number of Knesset seats picked up by Charedi parties not grown, it even seems to be in decline (certainly if we believe the polls). One reason for this, if not the main reason, is the recent trend of Charedi voters abandoning their home base and moving to Israel’s political Right. According to a recent poll, this trend could double its weight in the coming elections and shift an entire seat’s worth of votes from the Charedi home camp. Charedi parties invest a great deal of effort in persuading themselves and others that this trend is marginal and has no chance of expanding. But if they wish to stem the tide, they would do well to invest more efforts in correcting the problems leading people to jump ship rather than deny the holes in the hull.

[C]ontrary to conventional wisdom pegging the Charedi rightward tilt to internal Charedi processes, I will argue that the Right has moved to bring the Charedim closer and increased their identification with the same

I will try below to explain why this process is happening. I believe the heart of the matter lies in the voters’ focal point of identification. The wandering of votes rightward points to more and more Charedim preferring to identify with “Israeliness” in its rightwing version than sectorial “Charediness.” However, contrary to conventional wisdom pegging the Charedi rightward tilt to internal Charedi processes, I will argue that the Right has moved to bring the Charedim closer and increased their identification with the same. The Charedi rightwing shift is a consequence of “Charedization” process that the Right has undergone in recent years, much more than an Israelization of the Charedim.

Who Created the Bloc?

Last month, UTJ Chairman and MK Moshe Gafni were interviewed by Yair Cherki of Channel 12 News, making the following statement: “There are people who want to smear me and say that Gafni will go with the Left, that under strain Gafni will form an alternative coalition. I will never enter a different government, even if we don’t get 61 seats. I am going with the Right. We need to go with the Likud in every event and at any price.”

Several days later, an interview with an Agudas Israel candidate for Knesset, Yitzchak Goldknopf, was aired on radio FM 103. The interviewers managed to get a quote from him implying that the option of going with the anti-Netanyahu Benny Gantz was on the table. Hardly a few minutes passed before Goldknopf made it unequivocally clear that “the report is a lie and a falsehood, taken totally out of context. Such things were never said. We will only go with the Right, headed by Binyamin Netanyahu.”

The nervous, tense, unequivocal tone was not due to some loyalty locket to Bibi hanging on the necks of Gafni and Goldknopf. The winds of change recently blowing within the Charedi public have strongly favored the rightwing camp generally, and Netanyahu specifically. Gafni and Goldknopf know this well.

From where does this solid loyalty to the Bibist camp derive? One possible explanation understands this trend as part of the “Israelization” of Charedi society, manifesting in a more prominent expression of political stances and general Zionist patriotism. But while this has some truth to it, I believe the deeper explanation runs in the opposite direction: Not only have Charedim moved towards the Right, but more significantly, the Right has moved towards the Charedim. The Israeli camp has changed, wrapping itself in a Tallis and changing its name. It is no longer the rightwing bloc; today, it has become the “faith bloc.”

The Israeli camp has changed, wrapping itself in a Tallis and changing its name. It is no longer the rightwing bloc; today, it has become the “faith bloc.”

This turn is sometimes attributed to Arthur Finkelstein, an American-Jewish elections consultant who advised Binyamin Netanyahu, among others. Until 20-30 years ago, the thesis that dominated elections was that everyone needs to seize the center: every candidate needs to win the middle since the Left and Right parts of the electorate will, in any event, cast their votes for the representative candidate. Thirty years ago, a new American thesis began to spread among election architects, by which victory will go to those who make the best use of the voting potential of their own camp. The victor will be whoever’s camp shows up to the polls in caravans of buses. According to legend, Netanyahu chose to adopt this approach and recruited Finkelstein to advise him on how to exhaust his rightwing electorate fully.

Finkelstein argued that the mindset driving all camps in Israel hung on the identity question: “What are you primarily – Jewish or Israeli?” Netanyahu, who understood that people in his camp felt “Jewish first,” has never looked back in his management of Israeli politics, emphasizing the Jewish alliance of the rightwing base at the expense of voters in the center.

One of the significant consequences of this move is the alliance of the Right and the Charedim. The more the Jewish identity of the rightwing camp became apparent, the tighter the connection of the Charedim to Israel’s rightwing camp.

The Religiosity of the Rightwing Camp

Thirty years ago, Dan Meridor and Limor Livnat were the princes of the Likud, and permit me to say they never encountered tradition. At most, they greeted it here and there from afar; certainly, they never came up close. Today, however, after the religious awakening of the “faith camp,” prominent MKs of the Right embrace Charedim and all that they represent with warmth and affection. Dudi Amsalem has thus declared his deep love for Charedim; Galit Distal fiercely defends Yeshiva students; and even Yoav Kisch, who began his political career canvassing against the Charedi exemptions from military service, gives impassioned speeches in favor of the Torah world. And Smotrich? Betzalel is a tried and true Charedi. Aside from the name of his party, he is “one of us.”

Gafni (until recently) hasn’t missed an opportunity to declare himself a leftist and Merav Michaeli’s best friend while distancing himself from the Sefardi mob leading the Likud

This couplehood of the Charedim and the Right has worked well for years, notwithstanding far from simple ideological disputes. But Charedi politicians, or at least some of them, were late in recognizing this. Gafni (until recently) hasn’t missed an opportunity to declare himself a leftist and Merav Michaeli’s best friend while distancing himself from the Sefardi mob leading the Likud. Shas also has trouble retroactively erasing its involvement in the Oslo Accords, and the excited alliance of Deri and Bibi hardly brings his voters to tears.

True, the younger UTJ and Shas MKs are more rightwing, and this props up their numbers in the polls, but there are not a few Charedim whose rightwards shift is far stronger than their parties’ following suit. The (Right-leaning) Pindrus fig leaf simply isn’t enough for them. And thus, we find Smotrich and Ben Gvir picking up steam with young Charedim, who prefer to find a home in the “faith camp.”

I should note, however, that the primary beneficiary of the Charedi rightward shift is not Likud. There are few Charedi Likudniks. Admirers of Netanyahu among Charedim know that UTJ, Shas, and Smotrich/Ben Gvir have all sworn loyalty to Netanyahu, which is why a preference for Netanyahu is not sufficient reason for identifying with a secular party like Likud. The majority of Charedim voting outside the traditional Charedi camp are going to the Religious Zionist party – Smotrich and Ben Gvir.

Chassidim Seeking a Home

In this context, it is fascinating to examine the different trends that separate UTJ and Agudah. They might seem like one party, but a closer look shows that their electorates are far from the same.

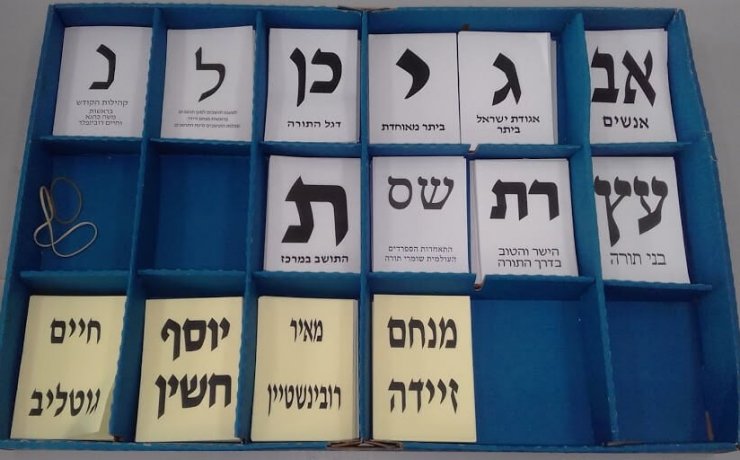

According to the official website of the Central Elections Committee, in the last elections of the 24th Knesset, 79.24% of the residents of Modiin Illit voted UTJ, 17.56% voted Shas, and 2.21% voted for the Religious Zionist party. In Beitar Illit, a slightly more Chassidic town, 60. 22% voted UTJ, 27.08% voted Shas, and 10.03% voted Religious Zionism.

If we go one election back, just a few months earlier, 80.02% voted UTJ in Modiin Illit, 18.30% voted Shas, and 0.38% voted for Ben Gvir and the Rightwing Party Union that ran separately. In Beitar Illit, 64.06% voted UTJ, 29.91% voted Shas, and 1.49% voted for both Ben Gvir and the Union.

The conclusions are relatively straightforward: between one election and another, in the space of a few months, the trend of Charedim abandoning Charedi parties for the Religious Zionist party is strongly apparent. In Beitar Illit, this trend is more extensive, though the percentage jump is similar, with approximately a sixfold increase in both. The numbers reflect a significant leap in a short period. As noted above, recent polls point to this trend doubling in the coming elections. But rather than prophecizing, I wish to dwell on the gap between Beitar Illit and Modiin Illit.

Despite the trend rate in Beitar Illit and Modiin Illit being fairly similar, the numbers remain very different, with vastly more voters in Beitar choosing non-Charedi parties than those in Modiin Illit. The natural explanation for the difference is that Beitar Illit is a Chassidic city, while Modiin Illit is Litvish. A little more than ten percent of voters in Beitar Illit voted for Religious Zionism in the last elections, while the number is closer to 2 percent in Modiin Illit. Shas is responsible for some of this difference, but what interests me is the change within UTJ. This gap seems to point to a difference between the Chassidic and Lithuanian communities.

With appropriate caution – another possibility is the difference between the more conservative Litvish faction in Modiin Illit and the more modernizing population of Beitar Illit – I wish to suggest that the flow of votes rightward is a broader phenomenon in the Chassidic community. If this is true, we can reach significant conclusions concerning the strength of Charedi identity in Litvish society by comparison with Chassidic communities.

Degel Versus Agudah: A Matter of Identity

If there is something Degel Ha-Torah has managed to cultivate in recent years, it’s a sense of Litvish group pride. The wars with the extremist Jerusalem Faction have strengthened the internal cohesion of the mainstream Litvish group. This is joined by the success of Rabbi Steinman zt” l in channeling this sense of Lithuanian belonging irrespective of any given leader’s charisma or lack thereof. To a great extent, the trend continued to strengthen under Rabbi Kaniyevsky, as confirmed by local government elections, in which the Litvish trounced the Chassidic representation.

The success of this collective identity is manifest in the fact that among Litvish Charedim, even those at the modern edges see themselves as part of the cohesive group. A Litvish Yeshiva student who goes out to work (and even wears a colored shirt) will continue to donate his charity money (ma’aser) to the local Kollel and will take eternal pride in having studied in one of the Litvish flagships. He will certainly not seek to hide his affiliation with his base community. Even if he does not live as a Kollel student, he will emphasize his connection to this Torah world, whether by supporting his righteous brother-in-law or by noting at every opportunity that Kollel students (rather than himself) are the pride and joy of the community.

By contrast, in Agudas Yisroel the reverse is happening, and the package is breaking down into its component items. In the past, Agudah was an all-Chassidic party. While dominated by this or that Chassidus, it allowed every Chassid to feel connected. But this bonding is rapidly coming apart. In 1989, Chabad pounded the pavement throughout the country to procure votes for Agudah; today, it is primarily (if not entirely) on Smotrich’s side. Chabad is a more complex case due to its tensions with UTJ, but it points to a trend.

In recent decades Agudah has lost its cohesion, becoming a loose federation, a collection of small groups, each with its own miniature identity. Under this arrangement, it is all too convenient for somebody who does not see himself as part of the “community of Chassidim in the Land of Israel” to find himself somewhere else. Small Chassidic groups, which lack representation, are encouraged to break out, usually rightward. In the last few days, polling has taken into account the realistic possibility that the two Ashkenazi parties, Agudah and Degel Ha-Torah, will run separately (the split is over Belz’s new educational arrangement with the State, a separate subject for discussion). The results were abysmal and telling. The Litvish Degel Ha-Torah received five seats, while Agudah was far beneath the required threshold. Presumably, for fear of losing so many votes, the parties will

The main challenge for Agudah is to recreate a Chassidic sense of pride. I don’t know how it will succeed in convincing the smaller Chassidic groups that their vote benefits them and that the party will genuinely represent each faction as much as it represents the dominant Chassidic groups. But if Agudah wishes to prevent the crash, it will have to rethink its trajectory.

Rejecting the Fixers?

In the present article, I assumed that the abandonment of Charedi parties involves identity. The critical question for the Charedi voter would be whether he sees himself as part of the home community or within the broader “faith camp” of the Israeli Right. Yet, turning my attention to the noise emerging from the social media channels surrounding me, one might get the impression that the principal reason for this growing flight is a rejection of the political style of Charedi parties.

Charedi parties have, over time, accumulated the reputation of being “fixers” – promoting politics without values, focused on interests alone, and ready to make every shady deal to achieve them. Charedi MKs are viewed as traditional activists (“machers”), contrary to the value-based agendas on which other MKs pride themselves. If I may be a little less politically correct, I can sum the issue up in a single word: Goldknopf.

Personally, I think the work of Charedi MKs is far broader than commonly thought about by critically-inclined Charedim. Yet, a thick cloud representing a lack of transparency and dark questions over sincerity hovers over them. And what can you do – the “fixeresque” atmosphere of smoke-filled rooms speaks far less to modernizing Charedim spending time on social media platforms.

Pindrus, Arbel, and Malkileli (and even Yaakov Asher) reek far less of old-style activism than their older counterparts. They are seen as diligent and even idealistic, presenting themselves with a sense of public mission

To some degree, the Charedi parties have begun to realize the need for a different kind of Knesset member. Both Degel and Agudah have brought in members of a younger generation that are fundamentally different from the old-timers. Pindrus, Arbel, and Malkileli (and even Yaakov Asher) reek far less of old-style activism than their older counterparts. They are seen as diligent and even idealistic, presenting themselves with a sense of public mission. This shift has significantly contributed to the image of the parties. Yet, despite these changes, Shas will still be headed by Deri, a man whose image needs no elaboration, while Agudah will be headed by Goldknopf, whose irreparably tarnished image raises the specter of lining personal pockets at the expense of young families and Kollel students. Smotrich, in stark contrast, is considered a hard-working ideologue who presents himself with sincerity and transparency. The option is proving tempting for many Charedi voters.

There is some truth in this analysis. Yet, I believe that in the Charedi mindset, voting remains primarily an expression of identity and belonging. This remains true even when the Charedi individual no longer casts his vote in favor of a Charedi political party – only that the rightwing parties he votes for provide an alternative identity focal point. Thanks to the Right moving closer to the Charedim, he feels he can remain devoutly Charedi while also being part of the greater Israeli story.

At the same time, voting for a non-Charedi party feeds the process of “Israelization” that parts of Charedi society are undergoing. As identity with Israel and its citizenry grows, so will our perception of voting as the appointment of delegates realizing a vision on behalf of the public. When that happens, Charedi delegates will be judged for their actions rather than for the tribal affiliation they represent.

Thanks, Efrat – enlightening piece!

Good analysis, but missing a big point that in our Internet age, everybody is aware of the personal interests of Rabbis/Rebbes/Institutions/Politicians, and the fact that Haredi politics is no longer the pure and pristine realization of Torah values is just turning people off. If our politics is just power play then people turn to something more ideological.

Would add Chabad to the analysis (last time round they had nobody to vote for). And the different factions who decide to vote or not to vote depending on what’s available and on current affairs.

Betar has a huge dropout rate, and this makes an impact on voting patterns. Another point: Goldknopf is a real problem. Everybody knows that he worried about himself and his institutions at the expense of teachers who eke out a meager salary, and he is turning away many voters.

Thanks for the piece, very informative and interesting. Would add that it seems the current leadership doesn’t reach the charisma and pull of previous times, as we saw lately with Rav Kaniesvsky zt”l. This will probably harm the Lithuanian vote.

There is certainly an ongoing process of “Israelization” taking place, particularly among younger Haredim. But there is also a broader long-term process at play, — namely, an ever-growing sense of civic responsibility, the realization that Haredi citizens of the State of Israel share in common with their fellow citizens a whole range of social, economic, military, and other concerns which transcend the narrow special-interest agendas of the Haredi parties. This is a healthy sign of political maturation.

It’s surprising that the disaster at Meron is not mentioned.

Let us recall who it was that assured the public before that Lag Ba’omer that “all would be well,” and that the chareidi parties fought vehemently against the formation of a committee of inquiry into a horrific event whose victims were their own contstituents.

It doesn’t seem so surprising that many would choose not to vote for the elements responsible for that calamity.

Finkelstein argued that the mindset driving all camps in Israel hung on the identity question: “What are you primarily – Jewish or Israeli?” Netanyahu, who understood that people in his camp felt “Jewish first,” has never looked back in his management of Israeli politics, emphasizing the Jewish alliance of the rightwing base at the expense of voters in the center.

======================================

And how do you maintain national unity in this model ( I’m assuming national unity is part of having a people/nation)?

KT

The process started in 1977 with Menachem Begin getting the Bloc set up and Aguda reps assuming governmental responsibility.