As a child growing up in London, I knew Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt”l, who then served as Rabbi of Marble Arch Synagogue, mostly as the father of my classmate Josh. Later, when he was appointed Chief Rabbi of the UK, I knew him from afar – a public figure managing the affairs of British Jewry and its relationship with the authorities. Finally, over the last few years, I came to know him as a great Torah-minded intellectual seeking to deliver a message not just to external audiences but primarily to his own people.

At our last meeting, a couple of years ago in Jerusalem, he made an unforgettable statement: “For too many years, I was predominantly a rabbi to the Goyim; now I wish to be a rabbi to the Jews.” I remarked that we do not have many “rabbis to the Goyim” like himself – figures who represented Judaism with depth and elegance to outside audiences, fulfilling the words of Yeshayahu: “And I made you as a light unto the nations, to be My salvation to the end of the earth” (Yeshayahu 49:6). “This is exactly why we need to focus on the Jews,” he retorted with a smile. He later clarified that his reference, to no small degree, referred to Charedi society.

At our last meeting, a couple of years ago in Jerusalem, he made an unforgettable statement: “For too many years, I was predominantly a rabbi to the goyim; now I wish to be a rabbi to the Jews.”

I believe, indeed, that Rabbi Sacks had an important message specifically for us in Israel’s Charedi community – a message bursting forth from the depth of his writings and the fullness of his life. The context of most of his work was albeit vastly different from that in which we ourselves live. Yet, if we but lend an ear with sufficient sensitivity, we ought to see how relevant and elevating his message is for us.

Who Will Extinguish the Flames?

The midrash tells us how Avraham Avinu became acquainted with God, explaining the reason why He first turned to Avraham:

“Hashem said to Avram: Leave your land, your birthplace and your father’s house.…” To what may this be compared? To a man who was traveling from place to place when he saw a palace in flames. He wondered, “Is it possible that the palace lacks an owner?” The owner of the palace looked out and said, “I am the owner of the palace.” So Avraham our father said, “Is it possible that the world lacks a ruler?” The Holy One, blessed be He, looked out and said to him, “I am the ruler, the Sovereign of the universe.”

Long before he published these words in his A Letter in the Scroll (later Radical Then, Radical Now), Rabbi Sacks spoke passionately about the words of the midrash, interpreting the “palace in flames” as a reference to our world: a beautiful palace full of chaos, evil, violence, and injustice. It cannot be, Avraham Avinu reasoned, that somebody had made such a beautiful palace and then abandoned it to a cruel fate. “How, in a world created by a good God, could there be so much evil? If someone takes the trouble to build a palace, do they leave it to the flames?” Clearly, someone was responsible for putting out the fire – but who was that someone? The question led Avraham Avinu to faith in Hashem. As Rabbi Sacks explains in his Haggadah, Judaism encourages the asking of questions to the degree that we must prod those who do not know how to ask. Absent questions, we lose our ability to learn, to grow, to believe. But what is the answer to Avraham’s question?

The answer – the answer of Avraham Avinu, the answer of Judaism – is that the responsibility for putting out the fire lies with humankind. God is the master of the palace, and He reveals Himself to those willing to partner Him in extinguishing the flames – the task of Tikkun Olan. When the actions of man are guided by the command of God, he becomes a partner in the work of creation:

The faith of Judaism, beginning with Abraham, reaching its most detailed expression in the covenant of Sinai, envisaged by the prophets and articulated by the sages, is that, by acting in response to the call of God, collectively we can change the world. The flames of injustice, violence, and oppression are not inevitable. The victory of the strong over the weak, the many over the few, the manipulative over those who act with integrity, even though they have happened at most times and in most places, are not written into the structure of the universe. They may be natural, but God is above nature, and because God communicates with man, man too can defeat nature. Judaism is the revolutionary moment at which humanity refuses to accept the world that is.

In a video that has gone viral since his passing, Rabbi Sacks spoke of the problem of evil: Why do bad things that happen to good people? How can we understand this? He explained to the questioner that if in the past (when her mother had asked the same question) his response stopped at our inability to comprehend all that God does, he now had an additional insight: “God does not want us to understand,” and therefore we are unable to understand. He does not want us to understand, because He does not wish us to accept evil as a fact of life, as a given. If we understood, perhaps we would not fight with quite the same conviction to remove evil from the world. Therefore, we don’t understand.

He expected others – Jews and non-Jews alike – to internalize the importance of taking responsibility, to understand that if there is evil and injustice in the world then the responsibility for remedying them falls upon us. And he led by example.

Rabbi Sacks practiced what he preached. He expected others – Jews and non-Jews alike – to internalize the importance of taking responsibility, to understand that if evil and injustice are present in the world then the responsibility for remedying them falls upon us. And he led by example.

A Good Leader and a Great Leader

Rabbi Sacks’ fundamental message of taking responsibility recalls one of the formative moments in his life – a moment of which he spoke often – when he visited the Lubavitch Rebbe in 1968. As a student at Cambridge University, Rabbi Sacks traveled to the United States to meet the Rebbe and consult with him regarding his own theological and philosophical doubts. After a considerable delay, including a three-day greyhound tour from America’s West Coast to its East Coast, he met the Rebbe, presented him with a list of intellectual and philosophical questions, and received appropriately intellectual and philosophical answers. The Rebbe then asked him about his life: How many Jewish students were there at Cambridge? How many of them were involved in Jewish life? What was he doing to get more Jewish students involved?

[T]he Rebbe stopped him mid-sentence and commented: “No-one ‘finds’ himself in a situation; you put yourself in a situation. And if you put yourself in one situation, you can put yourself in another situation.”

As a polite Brit with a solid ability to construct complex sentences, Rabbi Sacks (who had no interest in becoming a Lubavitch shaliach) began to make excuses: “In the situation in which I find myself…” But the Rebbe stopped him mid-sentence and commented: “No-one ‘finds’ himself in a situation; you put yourself in a situation. And if you put yourself in one situation, you can put yourself in another situation.”

“This sentence,” concluded Rabbi Sacks, “changed my life.” When he related the anecdote to Chabad shluchim (at the international conference of 2011), he went on to note that the Lubavitch Rebbe embodied the difference between a good leader and a great one: The good leader creates followers; the great leader creates other leaders. That speech revealed the basic trait that turned Rabbi Sacks himself into a leader: his determination not to accept circumstances as a given. We choose our circumstances, and we can choose to change them.

Rabbi Sacks considered this trait as relevant for individuals, groups, and even the entire Jewish People. An individual becomes a leader when he fully absorbs the burden of responsibility tasked upon him, while the Jewish nation earns the privilege to become a leader among the nations thanks to the same state of mind. This we have done throughout – from the days of Avraham Avinu, through the prophecy of “This nation which I created for myself, they will tell my glory” (Yeshayahu 43:21), to Hillel the Elder’s statement: “If I am not for myself, who am I?” The greatness of a leader is measured by the degree of responsibility he is willing to accept upon himself, and our greatness is measured by our commitment to the responsibility of bringing the word of God – and “all His goodness,” be it moral, spiritual, and even material – into the world.

Rabbi Sacks, who began his path in the rabbinate shortly after that encounter (and following another visit to the Lubavitcher Rebbe) never stopped expanding his circles of responsibility: from serving as the rabbi of a small community to taking on the rabbinate of a central synagogue, and from there to becoming the Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth. Finally, he achieved truly global influence thanks to an unending flurry of lectures and books, and his pioneering efforts – certainly as a man of religion – in the field of new media. He never stopped “creating leaders,” some of whom I am personally acquainted with. He became a great leader.

Small State, Big Citizens

As Chief Rabbi of a large, important country, Rabbi Sacks had to develop exceptional diplomatic skills. Some may argue that some of his writings suffer from an excess of diplomacy; he needed to exercise caution in expressing himself. But when it came to the virtue of taking responsibility and its various corollaries, he was forever clear and firm.

At every opportunity, he spoke and wrote against the “victim mentality” common to today’s cultural atmosphere – the tendency to “become the victim” and blame others instead of taking responsibility for ourselves and taking the necessary steps to achieve growth and prosperity. “Hate and the blame culture go hand in hand,” he argued in his discussion of radical Islam, “for they are both strategies of denial. ” Noting the trend toward prescribing medications to treat various emotional or mental ailments, he expressed concern about the effect it had on personal responsibility – the recognition that with proper guidance, a person can sometimes extricate himself from his predicament by means of his own efforts. Perhaps more than any other issue, he emphasized the enormous danger to modern society presented by secularization. He saw secularization as yet another flight from responsibility: moral responsibility, responsibility towards an internal truth, and responsibility towards a human society that has already begun to show signs of disintegration.

He saw secularization as yet another flight from responsibility: moral responsibility, responsibility towards an internal truth, and responsibility towards a human society which has already begun to show signs of disintegration

His political thinking is too complex to summarize in a few sentences, but even here it is worth noting the emphasis he placed on the value of taking responsibility. As a prerequisite for responsibility, he spoke often of freedom – a “politics of freedom” birthed at Mount Sinai, from which it spread to shaped modern reality. When man is free, he can answer the call to responsibility – personal responsibility as well as a civic responsibility. In the latter context, he deeply believed in the governmental model of liberal democracy, drawing inspiration from the writings of Alexis de Tocqueville on the one hand and Abarbanel on the other, since both believed in limiting the rule of man by man while empowering the individual, the community, local government and other organized forms of civil society.

He applied this approach – a “minimalist approach,” as he called it – even to the State of Israel, where he wished to see minimal coercion and maximal personal and communal responsibility. At the same time, he believed it wrong to expect states to be “neutral” as to the good life. A state has the right to determine the character of civic responsibility, and it is a corresponding duty of citizens to be acquainted with the fundamentals of local culture. Just as it is “inconceivable” (as he put it in a small Jerusalem gathering I attended some years ago) that a child raised in England should grow up without knowing Shakespeare, so it is self-evident that every child in Israel should know the Bible and become acquainted with the rudiments of Jewish heritage and tradition. Only thus can he carry out his civic duties as a citizen of the State of Israel.

He believed the purpose of the State of Israel is to allow its citizens to realize their responsibility within a Jewish national framework. The state must determine a Jewish national character manifest in its institutions, language, culture and civic activity – but without limiting the freedom and responsibility of its citizens

Rabbi Sacks saw our covenant with God – the partnership of man with the Creator of the Universe – as enormous empowerment and a profound responsibility at once. He believed the purpose of the State of Israel is to allow its citizens to realize their responsibility within a Jewish national framework. The state must determine a Jewish national character manifest in its institutions, language, culture, and civic activity – but without curtailing the freedom and responsibility of its citizens.

The Article That Never Was

My last meeting with Rabbi Sacks focused on Charedi society in Israel. I cannot fully recall the details of the conversation, but the general impression remains strong in my memory. He saw enormous potential in Charedi society, admiring its ability to preserve the core values of Jewish living while expecting it to share the spiritual goods it had accumulated with the entire Jewish People (and even beyond). He was pleased to hear about the formation of Tzarich Iyun as an intellectual Charedi publication, and even proposed submitting an article – a proposal that did not reach fruition (for which I accept full responsibility) and now never will. Yet, I believe his article might well have included an argument, embedded in his elegant prose and substantiated by profound words of Torah and wisdom, for taking responsibility.

God turns to Adam and demands he takes responsibility: “Where are you?” Rabbi Sacks stressed that the call for responsibility is not limited to Adam, who was derelict in his assigned duties; it is rather shared by all people and all groups. “If leadership is the solution,” he writes on Bereishis, “what is the problem?” He answers, based on the failures chronicled in the Torah, that “The problem is a failure of responsibility.”

For many years, Charedi society in Israel declined taking responsibility in the broad, national sense, focussing its energies on rebuilding communities and Torah centers that were destroyed in the Shoa. The justified fear lest secular culture and liberal values permeate the vineyard of Israel, alongside constant tension with the Zionist redefinition of what it means to be Jewish, restricted the boundaries of responsibility – some exceptions aside – to concern for the integrity of the internal community, and to inviting others to join.

Rabbi Sacks reminds us just how much this situation is forced by circumstances, a bedieved “state of emergency.” it cannot be the natural or the permanent state of affairs. With the growth of Charedi society and the increased interface between it and the general Jewish public, Rabbi Sacks teaches us that we are duty-bound – as individuals and as communities – to search for opportunities to expand the realm of our responsibility, to take hold of them as though they were precious stones, and to see them as both a privilege and an obligation. Beyond worldly responsibilities, it is up to us to show how Torah is relevant for the building and function of a Jewish state, and for translating our own values into a language that can be meaningful even to those who are distant from Torah Judaism.

Most of us are unlikely to straddle the circumstances and personas that Rabbi Sacks touched. But the force that drove him, the internal motion which accompanied everything he did – a Divine movement dwelling deep within him – is a movement we can all adopt, absorb, implement

Rabbi Sacks lived his life in a world very different from that of our daily surroundings. He was enmeshed in a different language and culture; his Torah encompassed an infinite scope of knowledge and wisdom collected from far and wide, and his Judaism encompassed worlds and corresponded with other religions and nations. He met with kings and counts, with statesmen and national leaders, and left a strong impression on them all – an impression of Divine goodness, of morality, and of Torah. David Cameron called him “my rabbi,” noting that he provided not only a religious voice for Britain but even a moral voice, and praising – as did Tony Blair and other prominent leaders – his influential contribution to public life in the UK. The Prince of Wales deliberately misquoted Yeshayahu in stating that Rabbi sacks had been “a light unto this nation.” Most of us are unlikely to straddle the circumstances and personas that Rabbi Sacks touched. But the force that drove him, the internal motion that accompanied everything he did – a Divine movement dwelling deep within him – is a movement we can all adopt, absorb, implement.

“Hillel passes sentence on the poor; Rabbi Eliezer ben Charsom passes sentence on the rich; Yosef passes sentence on the wicked.” To extend the list, Rabbi Sacks passes sentence on those who cling to their life circumstances and teaches us, through both his brilliant writing and his exceptional life, to choose our own circumstances and to take responsibility.

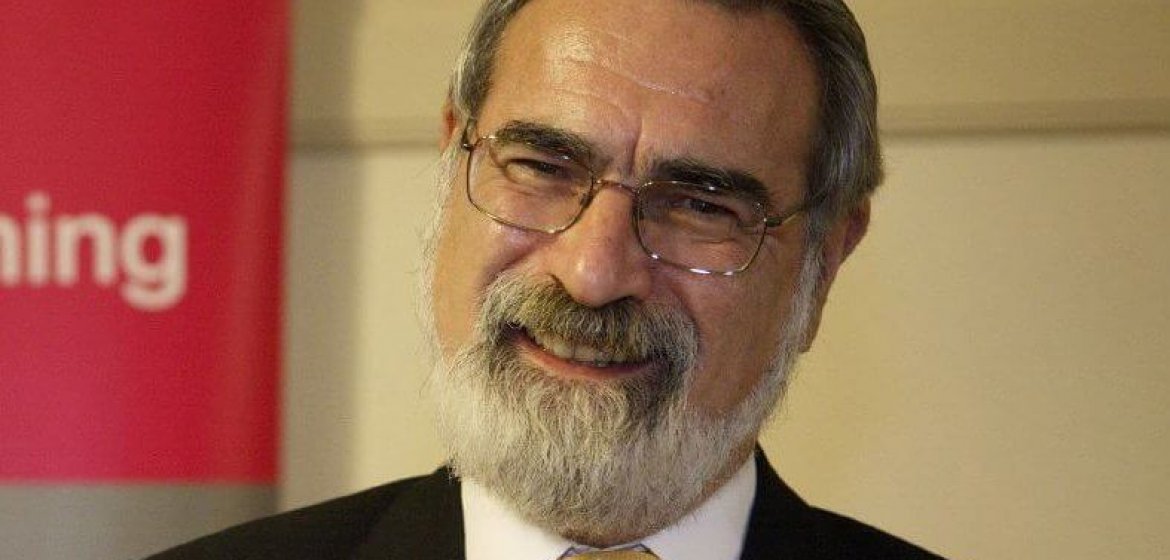

Photograph: cooperniall from England, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Excellently written! Would that we as the torchbearers of the light do our duty and reveal that light as far and as brightly as we can

A beautiful essay! All Jews share a responsibility to maintain, if not strengthen, Torah-based Judaism. to the Charedi community for holding steadfast to Torah values And teaching them to the next generation. Only by keeping Torah Judaism strong and along can we hope to carry out the mission of helping each other and humankind that Rabbi Sacks laid out for us. This will become increasingly important In the days and years to cone. The world will need HaShem’s help to deal with pandemics and the consequences of global warming. Avraham Avinu knew that Sodom and Gemorah were irreparable. Yet, he plead with HaShem. Perhaps in doing so he teaches us that If HaShem finds enough Tzaddikim in our world of much evil, and if sees enough acts of צדקה ומשפט to help others from Jews and non-Jews,, He will nevertheless be במעשיו שוחח and bring about the תיקון עולם במהרה that we daven for every day.

The Satmar Rebbe (the real Satmar Rebbe, warts and all) was wont to say the the reason why Hashem wouldn’t have destroyed Sedom had there been 10 tzadikim is “because had there been 10 tzadikim they would have destroyed it all by themselves”. Brillliant, funny, true.

כל פעם עליך לשאול מה ה’ רוצה ממך ואין אדם יכול להחליט לה’ מה הוא רוצה מן האדם, ולכן כל הרעיונות שכתבת יפים מאד, אך הבעיה היא שיש לנו תורה ברורה מאד שרק דרכה אנו יודעים מה ה’ רוצה מהאדם ושם פשוט לא כתוב את מה שכתבת. בעיה קטנה.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks does not need interpretation as he himself is the great interpreter and guide to Torah Judaism.

Even as we read this, some 6,500 Chabad shluchim are meeting in Brooklyn for their annual kinus. Every single one of them, like Rabbi Sacks, is inspired by the Rebbe to live a life of joyous altruism, a total commitment to the needs of their fellow Jews, and of underwriting the Jewish future worldwide. The genius of the Rebbe reveals itself afresh each day as Chabad refuses to get stuck at ‘histakel b’orayta’ by reaching up and out to the all-important ‘uvara olma’ which. after all, is the entire point.