In an eloquent article published on this platform a short time ago, Aharon Saltz argued that there is a need for a systematic ideology, a new hashkafa for the Charedi man-at-work. His article raised many points I agree with. However, I wish to comment on the general framing of his discussion, addressing the overall discourse around “working Charedim” rather than any specific argument. I will claim that the fundamental problem of Charedim-at-work is not the lack of an ideology. Instead, it is the very fact that the situation is perceived as a problem.

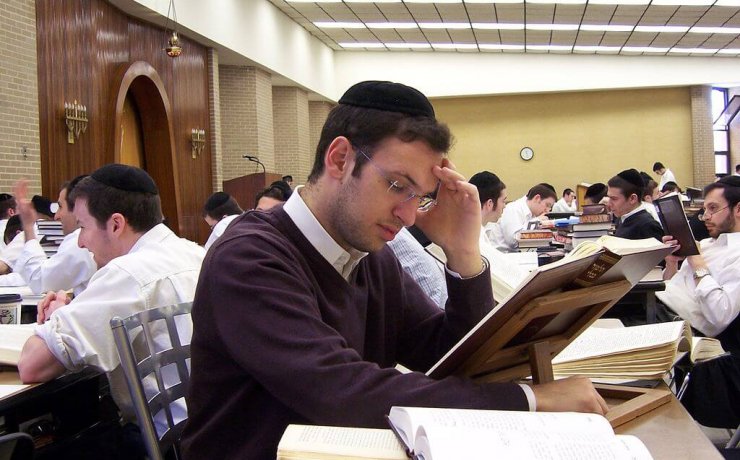

Let’s begin with semantics: “working Charedim.” The term, which is becoming increasingly common, especially among Charedi workers themselves, is highly problematic (though I will use it in this piece for the sake of convenience). It assumes that a person going to work is an exception to basic norms and expectations and that the phenomenon is something novel, out of the ordinary. Talking about Charedim at work gives the impression that Charedi workers are the exception to the rule. They deviate from the “ordinary,” the normal person who does not work. In reality, the very opposite is true. Making a living, working, and having a profession is the basic human norm, and so they ought to be—halachically, morally, religiously, and humanly.

Talking about Charedim at work gives the impression that Charedi workers are the exception to the rule. They deviate from the “ordinary,” the normal person who does not work

Accepting the label “working Charedim” is thus a nod of agreement on our part to a distorted attitude on the part of working Charedim themselves. It defines them as living a life of inadequacy that fails to live up to the full potential of life. As such, the very label justifies the common labeling of men at work as third-class in Charedi society. To me, talk of working Charedim needing an ideology only serves to cement this unfortunate trend. As a matter of fact, the shaky and dubious worldview is held by “Charedim who rejects the legitimacy of work,” and not by the “normal Charedim” (forgive me for the term) who lead their life in accordance with Derech Eretz—following the good and trodden path of human living, even of Charedi living.

There is nothing more ideal than work

The Shulchan Aruch, describing the order of a Jew’s day, includes the duty to work for a living: “Following this [prayer and breakfast] he must go to work, for Torah that is not joined by labor eventually fails, and leads to sinfulness” (Orach Chaim 156:1). This is the regular path that every Jew takes, as founded on the Mishnah in Avos. Work was never considered abnormal in Jewish and Halachic history.

Of course, we are aware of the divergent views of our Sages on the matter. Rabbi Shimon b. Yochai disputes Rabbi Yishmael’s view that one should “lead one’s Torah study life with the way of the world,” yet the Gemara declares (citing Abaye) that many did as Rabbi Shimon prescribed and failed. Rav Nehorai refrained from teaching his son anything but Torah, but his view is unconventional and goes unmentioned by Halachic tradition. Such opinions are limited to elite individuals who dedicate themselves to Torah study, and even the formulation of the relevant statements indicates their exclusive nature (“I do not teach my children anything but Torah”). When it comes to guiding the general public, this puritanical path is everywhere described as a failure.

The path of pure, unadulterated Torah study remains one that highly qualified and motivated individuals can aspire to; it is not a normative description of the Jewish way of life. The entire Torah relates in detail to matters of working life. This includes relations between employers and employees, farmers and those who work the land, and the right and the just in business transactions. All of this would be completely unnecessary if the Jewish people were a people of Yeshiva men. If this were the case, the Shulchan Aruch would focus on the laws of prayer and Shabbos alone.

The idea of a lifestyle without work is an exception and itself a remarkable innovation of the modern day; work, as we’ve always known it, is the cornerstone of every person’s life

All this is abundantly simple, yet it flies in the face of the “working Charedim” label, which turns the tables entirely upside down. In the history of the Jewish people, there was never a debate on this matter, and it certainly has no bearing on the endlessly discussed ideas of “Torah and Derech Eretz.” Jews throughout the ages worked for their living like any other person. Rabbi Hirsch’s “Torah and Derech Eretz” and the ideological movements in Germany stand for completely different ideas, broadly constituted in full participation in German education and citizenship. This polemic is light years away from the (so-called) “debate” over “work.” The idea of a lifestyle without work is an exception and itself a remarkable innovation of the modern day; work, as we’ve always known it, is the cornerstone of every person’s life.

True, there is a voluminous range of Halachic material concerning learning Torah while being supported by the community. Many scholars and leaders saw this as an ideal, while the Rambam saw it as a desecration of Hashem’s Name and a degradation of our religion. But these polemics concerned individuals. It never occurred to anyone in Jewish history to instruct an entire public to occupy the benches in the study hall. To see this as a general public directive is strange and distorted in every way.

The point I make is that there is no ideological debate to speak of—and therefore no need for a “new ideology” for working Charedim. The fact that a person works for a living is well-established (or should be) in society. A person who does not work for a living, according to the Sages, will move on “to despoil humankind.” This is not a point of view but rather a simple description of fact. Work is an inseparable part of life, just as buying food and living under one roof are inseparable parts of life. There is no need for a “worldview” or “ideology” to legitimize the most elementary things in a person’s life.

Distinguishing between the sacred and the secular

An important and somewhat worrisome trend worthy of mention is the attempt to justify work by employing new and innovative argumentation. Some turn to Chasidism, which sanctifies everyday life, building a home for Hashem in the lower worlds and bestowing deep meaning to “everyday life.” Others look to Kabbalah, turning to the sublime and mysterious. These trends are part of the problem. The attempt to justify the situation of working Charedim by means of concepts hailing from spheres of holiness achieves exactly the opposite effect. It validates the approach that a healthy, moral, and normal life of civilized humanity needs a radical justification: “to sanctify the profane,” to demonstrate that “there is holiness even in work,” and that we can glorify Hashem or discover “holy sparks” even in the mundane.

What needs to change is the basic understanding that living a healthy, moral, and normal life, being a civilized human being, is not a matter that requires radical justification and “sanctification” of any kind. The Torah addresses a regular person—a regular Jew. It does not produce or mean to produce artificial people. Mothers give birth to children, and children live and thrive by the food they eat and the roof over their heads. And in adult life, boys who grow up go to work—no less (and generally more) than girls. The Torah relates to such regular people who eat, sleep, work, marry, beget children, and engage in various activities that elevate and sanctify themselves. This, together with the elevation the Torah demands of us, is the good life itself.

What needs to change is the basic understanding that living a healthy, moral, and normal life, being a civilized human being, is not a matter that requires radical justification and “sanctification” of any kind

The Torah never sought to abolish the mundane nor to “sanctify” it. What the Torah asks is “to differentiate between the holy and the profane” and introduce a dimension of holiness into life. To think that normal human life is justified only because it serves an elevated ideal of holiness, only because “it isn’t really mundane, but, deep down, it is holy” is absurd. It is an expression of the sterile nature of the worldview and philosophy that has spread within our community.

Entertaining the thought that regular life—working for a living—requires ideological justification has a dramatic impact on healthy living itself. The lack of readiness to examine facts as they are, to look at reality directly, and to live naturally in the world leads to very large social, moral, and religious distortions. It may manifest in insensitivity to people, turning a blind eye to social and moral injustices, and even total disregard of considerations of utility and realistic conditions. In its extreme manifestation, it can represent a broader detachment from reality that becomes deeply harmful when applied to a complete society or state.

Perhaps this is what the Sages referred to when they stated that “anyone who says I have nothing but Torah, even Torah he does not have” (Yevamos 109b), or when they attributed the destruction of the Temple to people who “based their rulings on the strict letter of Torah law” (Bava Metzia 30a). A similar case in point is Chazal’s weeping over Torah students who, even as a man was murdered before them, disputed the impurity or otherwise of the knife dripping with blood (Yma 23a). We need to steer clear of such modes of thinking.

The non-working Charedi needs a worldview

It is not “working Charedim” who need a worldview, but rather the “non-working Charedim”. The situation whereby working Charedim are expected to provide accountability for their way of life is no less than absurd and turns the tables quite upside down. Is educating the next generation for a life devoid of financial security normal? Is a lifestyle organized such that an entire society, which is growing to the point of becoming a majority, relies on the kindness of others and does not take the responsibility of self-sustenance into its own hands, a normal life from a Halachic, Torah, and moral point of view?

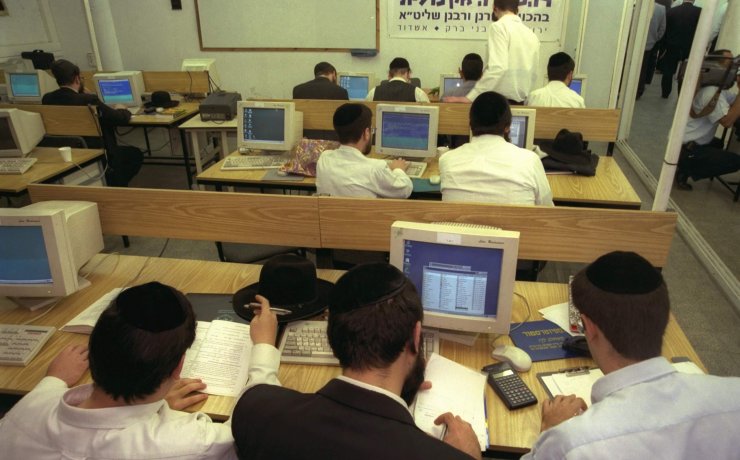

The fact that an entire community lives by the grace of mainly secular Jews who study secular subjects and become high-tech professionals ought to grab our attention, as should the situation in which individuals not built for continuous Gemara learning have to remain in the Beis Midrash for social reasons. Given high dropout rates within Charedi society, which are at least a partial result of these facts, can we justify this situation from a Halachic and moral point of view?

While the commitment to Torah is admirable, our situation is such that an entire community does not take upon itself the duty to bear the burden of human living in basic terms of responsibility: collective responsibility, social responsibility, national responsibility, ethical responsibility, and responsibility towards its own descendants. We should be asking ourselves the question: Is all this proper from a Halachic and ethical point of view? Sporadic quotes from Chazal that glorify and praise the study of the Torah at the expense of everything else are simply inappropriate as a response. Our context is totally different from that in which such quotes were written.

There is no intent here to say anything against Kollel men and Yeshiva students. I strongly believe in the necessity of the Yeshiva and Kollel institutions, and I am inclined to think (unlike the Rambam) that it is appropriate and proper to subsidize and finance Torah students from public coffers. This is certainly true at a time like today, in a modern country and with a developed economy, where it is possible to finance humanities studies in universities. But the real question is on a completely different level. It was never about individuals who were uniquely inspired but about the entire community: Is there a justification for the seemingly irresponsible conduct of an entire public?

One Knesset member speaks about how Gemara studies will “save the Israeli economy,” and another claims that there is no need to worry about health matters because “Rabbi Firer is doing the work.” We cannot afford to continue in this way

We seem to have brought ourselves to a dangerous situation in which an entire public holds principles detached from reality that are presented as ideals. One Knesset member speaks about how Gemara studies will “save the Israeli economy,” and another claims that there is no need to worry about health matters because “Rabbi Firer is doing the work.” We cannot afford to continue in this way; we are a public whose decisions will not only affect us but will also determine the country’s track in the not-distant future. If the Charedi public continues to tread an unrealistic path, we will very quickly become a third-world country, and people will not be able to study Torah properly even if they really desire to.

Indeed, it is not the working Charedi who needs a worldview, but rather the non-working Charedi. He is the innovator. The burden of proof rests upon him. Deviating from regular earthly norms, he is the one who is challenged by halachic and moral problems of the first degree, and tasked with dealing with the consequences of his choices.

Today’s distorted sociological situation presents the working Charedim as third class. As a result, they need to hesitantly justify their existence. But these are not “working Charedim” but regular, God-fearing people who set aside times for Torah study, observe Mitzvos, and love the Torah and those who study it. This is the image of an ordinary religious Jew. By contrast, the “society of learners” (as Charedi-Litvish society is sometimes termed) needs to provide more information to justify its position, showing how vital, relevant, and necessary its Torah study is to the people of Israel and how it doesn’t come at the expense of basic obligations of providing for households and fulfilling the duties listed in every Ketubah. We cannot unthinkingly raise our children to a life of poverty and deprivation and ignore our civic responsibilities and the question of whether our actions glorify Hashem or otherwise.

These, and not the question of “working Charedim,” are the questions that require hard-headed thinking.

No Need for Ideology; Just Stand Proud

It’s easy for us to blame the media and those “on the other side of the fence” when they bring up the issues I mentioned above. We put ourselves on the defensive and automatically attack whoever dares to criticize us. Right away, there will be those who point out the anti-Semitism of the speakers, the “hatred of the Charedim,” the incitement and intimidation, and inaccurate statistics. It is easy to ignore the dirty remarks of Lieberman and Natan Zahavi so as to dismiss pointed questions entirely—and I am not saying that there is no justification for such responses. Yet, ultimately—and especially as Charedim—we must stop this circus and start asking ourselves these questions honestly from a place of moral and religious responsibility and reverence for Hashem. We must stop telling ourselves fairy tales about the Cossacks who are persecuting us.

It seems that working Charedim sometimes display symptoms of Stockholm syndrome. They bemoan their distance from the Charedi ideal and expend much energy in justifying being Kosher Charedi Jews loyal to the “pure Charedi ideology” (hashkafah tehorah). By clinging to the “working Charedi” label, they confirm and validate the view of the “non-working Charedim” and thus perceive themselves as joining forces and uniting. This is why we find so many working Charedim who are quick to declare that in matters of outlook, they are simple, ordinary Charedim, agreeing even to the indignities that working Charedim experience. Idealists will go even further and declare their secret wish to be “regular, non-working Charedim,” but they failed to meet the ideal or reach the bar.

How do we expect working Charedim to be God-fearing Jews who observe every minute Mitzvah if this distorted sociological rhetoric leaves them in the vulgar and disadvantaged place of the baalbas?

The cooperation of working Charedim with the view that presents them as those who chose the wrong path (sometimes due to having no other choice) is a tragedy. How can we expect the Charedi working man to have an ideology if from the very beginning he acquiesces to being second class in society if from the start he treats himself as a failure? How do we expect working Charedim to be God-fearing Jews who observe every minute Mitzvah if this distorted sociological rhetoric leaves them in the vulgar and disadvantaged place of the baalbas? Of course, the cycle is self-serving, the spiritual inferiority drawing the response of “look and see what happens to those who enter the workforce!”

Naturally, this makes no sense. What do we expect from people who we push time and again into existential doom and spiritual desolation and above all, into personal persecution? The Charedi worker requires more than an ideology. He needs a sense of pride. What needs to be done is not to stop cooperating with the sociological determination that working Charedim are not simply ordinary Charedim, no more and no less. This is the beginning of any solution to the challenges facing the Charedi individual today who has boldly decided to do what is expected of him as a God-fearing Jew.

Working Charedim are the primary focus of this decision. They need to raise their spiritual stature and stop listening to the claim that by fulfilling fundamental duties as a person and a Jew, they have somehow failed. It should be loudly declared that the situation whereby enrolment in institutions and status in matchmaking are affected by the choice to go to work is absurd. On the contrary, the working Charedi person should come mentally prepared “with his teachings in his hand,” be unashamed of those who mock him, and tell the truth—that he took the elementary step of taking responsibility for his life and his family, unlike those who seek to push him into a corner in the name of views that have no legs to stand on.

The Charedi mainstream is not being called to action; they are involved with themselves. This is a call to those who have been perversely dubbed “working Charedim.” Enough of this submissiveness. Go out bravely and sanctify Heaven wherever you go. There is nothing more ideal than you.

In the USA,there are many Charedim who are learner-earners and who learn on a very high level . There is nothing Bdieved about that at all

It seems to me that much of the opposition to work has come from long-standing fears that induction into the IDF would have irretrievably secularized Chareidim. Chareidi leaders believed that the IDF had this as a goal. If Israel had never begun its military draft, and military service was never an unstated condition or desirable qualification for some types of employment, would the Chareidi approach to work have been different?

Excellent article. One minor note. You write: “Of course, we are aware of the divergent views of our Sages on the matter. Rabbi Shimon b. Yochai disputes Rabbi Yishmael’s view that one should “lead one’s Torah study life with the way of the world,”

We do not raise possibly legitimate behavior based on ancient texts but on decided halakha; no one permits milk and chicken despite that view bring held by a Tanna. Working is halakha pesukah and citing opposing views that were not accepted except for yechidai segulah provides ammunition for continued anomolous behavior. Other than this lacuna, a well-needed and important perspective.

The idea of haredim eschewing work in order to learn Torah is truly ‘reform’ Judaism, an invention of the mid 20th Century that has zero basis in Torah and which, in fact, contravenes both written and oral Torah starting at Sinai. It came about as a malicious distortion of an understanding between Ben Gurion and the Chazon Ish whereby OUTSTANDING Torah scholars would be exempt from military service in order to learn Torah, as these men would produce serious scholarship and be a benefit to society as a whole, just as very gifted musicians or athletes are exempted as they are considered a national asset and treasure. Israeli haredim turned this idea of yehidei segulah avoiding the army in order to learn Torah on its head. and turned it into learning Torah in order to avoid the army for mobs of untalented men who have no business squandering their time and the nation’s assets by (as Ovadiah Yosef’s daughter said) wandering from window to window and from cigarette to cigarette. The ostensible justification for this massive sheker was that army service might undermine the frumkeit of the haredi soldier. Aside from the fact that fully 40% of IDF officers today are dati and that the incoming OC is religious, one has to wonder at how weak the haredi education is and how shaky the emunah of its adherents if they are so afraid of outside influences. Why would it not be the other way around, that the unshakeable faith of haredim would impact on the non religious soldiers with whom they serve? But the biggest sin of all here, far bigger than the collective grand larceny, is the crime committed against the haredi men who can never find out where their real skills and talents lay, who can never find fulfillment in their lives. who can never take pride in providing for their families b’kavod. For a huge and growing community to live on life support from the people they despise — for medicine, roads, security, electricity etc is terrible, especially for the tens of thousands of men whose lives are being wasted in a web of dependency and deceit.

Kach Mkublani mbeit avi abba vima – If you have the self esteem to know that what you are doing is right, then you don’t need the approval of those who hold a different opinion (BTW that’s what I try to tell my MO brethren as well)

KT

So, Mr. Gross claims that the arrangement whereby the charedi men don’t work and don’t serve in the army is only for a small number of unique individuals. Ask every Rosh Yeshiva today, and he’ll tell you that it’s for everybody (and they have quotes from Nefesh a-Chaim or whatnot to supposedly support their claim). So, how do we know who is right? Is this written anywhere? Are there records of the conversation between Ben Gurion and the Chazon Ish, or other records indicating what the Chazon Ish wanted the charedi society to look like?