Several weeks ago, on the 10th of Sivan, 5783 (30.5.2023), the world lost a tremendous Torah luminary, Rav Gershon Edelstein, zt”l, who stood at the rabbinic helm of Charedi-Litvish society and chaired the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah (Rabbinical Council of Degel HaTorah). His sole leadership began after the passing of Rav Chaim Kanievsky zt”l just a year ago, yet due to their different characters and fields of occupation, the two shared the leadership mantle for several years hitherto.

In contrast with Rav Chaim, who was exceptional in every sense, Rav Gershon was a quiet personality. Some would call him dull. It is hardly surprising that precious little has been written about him, whether in Torah magazines and journals or in academia. Yet, perhaps for this very reason, his leadership is worthy of note, writing, and deep appreciation.

In the following short lines, I want to discuss Rav Gershon’s legacy and the lessons we can draw from his hundred-year life. Strikingly for a leader of the Degel HaTorah rabbinic council, his legacy is primarily educational – a point that speaks volumes and is worthy of consideration. Following this, I want to highlight why this legacy is crucial for our time, ending with a suggested explanation of why he objected to the recent Charedi boycott of Angel’s Bakeries – a move that raised eyebrows.

On a personal note, I should mention that I was not close to Rav Gershon. I never studied in the illustrious Ponevezh Yeshiva, and my visits to Bnei Brak have always been infrequent at best. I observed him from afar and only recently, after his rise to prominence as a leader of the Charedi-Litvish community. I wish to note my appreciation of getting to know, by way of writing, something of this great individual.

Hashem is Not in the Earthquake

[The word of God] then said, “Go out and stand on the mountain before Hashem.” And behold, Hashem was passing, and a great, powerful wind, smashing mountains and breaking rocks, went before Hashem. “Hashem is not in the wind!” After the wind came an earthquake. “Hashem is not in the earthquake.” After the earthquake came a fire. “Hashem is not in the fire.” After the fire came a still, thin sound. (I Melachim 19:11-12)

No rabbinic leader of recent times has embodied the message conveyed to Eliyahu to the degree Rav Gershon did. Hashem is not present in the dazzling and the astounding. He is not present in the ecstatic, the euphoric, and the rapturous. He is not present in the neon lights but rather in silence. Rav Gershon embodied a holy and elevated version of the sound of silence.

By contrast with other Roshei Yeshiva, Rav Gershon was not a charismatic figure. He did not dazzle, and his Torah chiddushim are not cited with excitement by Yeshiva students worldwide. There was much about him that was quiet, organized, and stable to an art. His hours were regular; he was not one to sleep at 2:00 in the morning nor one to awaken at 4:00 am. The final salary slip he received from Ponevezh indicated seventy-five years of uninterrupted service at the Yeshiva. For nearly eighty years, he sounded the Shofar in the Yeshiva Rosh Hashanah davening, continuing to do so until his final year. He did virtually the same thing each day, each week until he reached the age of one hundred, when he died as he lived: quietly, without fanfare. His days simply ran out.

The fiery temperament of the Steipler, the total dominion of Rav Shach, the formidable and sometimes fearsome intensity of Rav Elyashiv, the holy prishus of Rav Aharon Leib, all zt”l – all of these were absent from

His entire world revolved around Torah – its study and its dissemination. His dedication to Torah was immense and even extreme. Yet, there was nothing radical about him. The fiery temperament of the Steipler, the total dominion of Rav Shach, the formidable and sometimes fearsome intensity of Rav Elyashiv, the holy prishus of Rav Aharon Leib, all zt”l – all of these were absent from him. His commitment to Torah was embedded in a harmonious relationship with the world. Not by chance, Rav Gershon was the first among prominent rabbinic leaders to have grown up within the system (or close by). He was exceptional in his normality.

The contrast with Rav Chaim was especially pronounced due to their joint leadership over several years. Rav Chaim epitomized the famous Bnei Brak idiom stating that Daas Torah hepech daas Baalei Batim – the opinion of a layperson, based predominantly on sheer common sense, is the opposite of true Torah wisdom. Nothing about Rav Chaim resonated with ordinary common sense: his uncanny Torah knowledge and method of Torah study, his often supernatural approach to issues both personal and communal, his unworldliness in every sense of the word – these and much besides reflected his disdain for the worldly. Rav Gershon was the very opposite. Within a Torah context, he embodied the unexceptional, the worldly, and the normal.

The most prominent example of this contrast was the Charedi response to the Covid-19 crisis. While Rav Chaim’s initial approach was to keep schools and religious institutions running as usual, claiming that the best way to defeat the virus was to strengthen ourselves in the upkeep of religious and moral duties, Rav Gershon was adamant that regulations be followed, that doing so was “a great religious obligation,” and that anyone not doing so was “deserving of punishment.” Down the line, Rav Chaim and his court came around, and the two rabbinic leaders jointly signed proclamations encouraging vaccinations.

More broadly, Bnei Brak is not known as a place that affords much respect to the regular ways of the world. It is known for its boundless energy, constant noise, passion, and zeal. If Tel Aviv is the nonstop city for Israel’s general population, then Tel Aviv is the Charedi equivalent, in which everything is somehow different. People in Bnei Brak talk differently, drive differently, and practice Jewish law differently from the rest of the world. On the final point, Rabbi Simcha Elberg penned a piece (in the sixties) dubbing Bnei Brak a “World of Strictures.” The norm, he explained, is that rabbis seek to harmonize between halacha and the world by seeking lenient rulings. In Bnei Brak, however, the opposite is the case. As a community rabbi with decades-long experience, he had never seen anything like it.

There is beauty to the Bnei Brak disposition. It reflects the vivacity of youth, the totality of truth, and the radicalism of an ongoing Charedi revolution. And there are also more challenging sides, the wars of the rival Ponevezh factions (or other politicized groups vying for power) being just one case in point. A friend whose son recently began studying at the Yeshiva told me that although he was deterred by the belligerent atmosphere, he understood that no other Yeshiva rivals what Ponevezh has to offer. Unlike the zealots of Jerusalem’s Old Yishuv, Bnei Brak does not negate or entirely disparage the world. It exists alongside it, accepting the world even as it deviates from some of its ways and principles.

Rav Gershon stood out against the backdrop of Bnei Brak. His quiet serenity, outstanding stability, and steadfast moderation that drew from a deep respect for “the ways of the world” made him a remarkable educator and leader. Since Rav Gerson’s principal legacy is educational, it is worth focussing on this crucial area.

A Legacy of Gratitude

What character trait most divides between the extreme and the moderate, the radical and the conservative? Though there is no single answer to the question, and much depends on time and place, a basic and profoundly meaningful factor is gratitude. The Ramban explains that those lacking the trait of gratitude cannot be accepted into the ranks of the Jewish People (his reference is to Amon and Moav, whose refusal to assist the Israelites demonstrated extreme ingratitude). Being Jewish is being grateful since gratitude is the gate through which we enter into our relationship with God.

A far-reaching expression (for a Charedi leader) of his gratitude was Rav Gershon’s attitude toward IDF soldiers and Zionist pioneers. “Even secular Jews who do not observe Torah and mitzvos,” he stated in a 2012 shiur in Ponevezh, “if they give up their lives to save lives out of love of others, they have a portion in the World to Come just as the martyrs of Lod who gave up their lives for the good of the city’s residents.” He told the story of a young man who was killed by the British while demonstrating on behalf of Jews who were not allowed to enter mandatory Palestine: “This young man didn’t believe and refused to recite Kaddish after his father’s death, yet was ready to give up his life for the sake of the Jewish refugees, and receives the World to Come. […] He did this out of nationalism, not the non-Jewish nationalism that derives from arrogance, but out of love for Jews.” Predictably, Rav Gershon was attacked for his statements. Nonetheless, he refused to retract or confirm the claim (which some had already suggested) that he had been misquoted.

Rav Gershon’s unusual conservatism, as described above, derived from the basic trait of gratitude, of perceiving and appreciating the goodness in the world, in society, and in others

Rav Gershon’s unusual conservatism, as described above, derived from the basic trait of gratitude, of perceiving and appreciating the goodness in the world, in society, and in others. “To my mind,” wrote Yuval Levin, “conservatism is gratitude. Conservatives tend to begin from gratitude for what is good and what works in our society and then strive to build on it, while liberals tend to begin from outrage at what is bad and broken and seek to uproot it.” This disposition and the humility that goes together with it – appreciating the good inspires humility in the face of the good we receive from others – were defining for Rav Gershon.

In contrast with many other Charedi leaders, Rav Gershon’s life was not marked by religious and political struggles but by constant dedication to strengthening and consolidating goodness. Not that he didn’t know how to fight. He was ready to cause an internal-Charedi political fallout by insisting that the kosher cellphone market be opened to competition. Fearful that the move could undermine the Chinuch Atzmai (Independent Education) Charedi school system, he also fought the “Belz proposal” that would have procured government funding for Charedi schools in exchange for studying English and mathematics. But such episodes were few and far between, lacking the antagonism that characterized other Charedi leaders. In the main, his focus remained staunchly on education. In this field, he was something of a maverick.

Rav Gershon championed an approach of respect and goodwill for every Jew. This was integral to his educational messaging, deemphasizing militant attitudes toward wrongdoers and highlighting the duty of upright conduct and respect. It was also the way he lived.

As multiple stories that emerged after his death testified, he abhorred the practice of “kicking recalcitrant children out of the house” and vehemently opposed it even when their behavior posed complex educational challenges for siblings

He especially stressed the need for love and understanding concerning children who had gone “off the derech,” which he believed was a core duty of every parent toward his children. He refused to accept parents who penalized their children for stepping off the path of parental and social expectations, tending to place responsibility on the parents rather than the children. When one young boy was severely punished because of his smoking addiction, Rav Gershon blamed his parents, who had allowed him to smoke on Purim. As multiple stories that emerged after his death testified, he abhorred the practice of “kicking recalcitrant children out of the house” and vehemently opposed it even when their behavior posed complex educational challenges for siblings. He told one father that if he thought separation between the children was essential, he should keep the recalcitrant child home and find alternative accommodation for the others.

He likewise rejected coercion of any type, striving to allow others to choose the good of their own volition rather than force it upon them. He would cite with disapproval the case of a father who agreed to buy his non-observant son a car, but only on condition that he doesn’t drive it on Shabbos. The condition, he argued, caused potentially irreversible harm. Our love for our children, and, indeed, for every Jew who has not turned himself into an enemy of religion, should be unconditional. Within boundaries, he was a lifelong proponent of “positive education,” of seeking and empowering the good within others, even when they were struggling.

The foundation for his approach was seeing the good in people. Appreciating it within others inspires us to strengthen and reinforce it, giving them hope and belief in their inherent goodness. Rav Edelstein’s educational messaging reflected his personality and dispositions. “Each according to his nature,” he would repeatedly say, hoping his young disciples would internalize the message – we all have different natures, but we all have profound goodness within us. “Do the just and the good,” he would often cite: deep down, we know what is good and just. He would demand “upright behavior in areas of bein adam le’chavero” – we all know what upright behavior is.

Rav Edelstein was able to pierce the superficial shell and see the goodness inherent in each of us. Therefore, he afforded deep respect to all human beings. Naturally, he was a staunch advocate for cooperation and coexistence, wherever possible.

The same disposition made Rav Edelstein sensitive to superficiality of any type. Sefarim were found in his home with superlative titles (which others bestowed on him) crossed out; he had no patience for such honorifics. When asked, at a gathering for youth, how one becomes a gedol hador, his immediate reply was that you first need to stop thinking about becoming the gedol hador. The interlocutor, Rabbi Kessler from Kiryat Sefer, was so shocked that he initially misheard and failed to fully understand even after being corrected.

Finding a Common Denominator

Over the past months, the need for a deep common denominator among Israeli-Jewish society has become abundantly clear. Even today, protests in Israel and abroad continue to cross red lines, and Israel cannot afford to become a fractured society; we are strong united, and strength, for Israel, is an existential need. This is why I disagree with the spirit of Eliyahu Levi’s recent article [Hebrew]. We should call out the small minority of “haters” whose contempt for religion turns them against their own people. As for the rest, they are brothers and sisters and should be treated as such.

One of Rav Gershon’s last instructions was to object to a Charedi boycott of “Angel’s Bakery,” even though Omer Bar-Lev, the chairman of Angel’s board, demonstrated outside Ponevezh Yeshiva, which was also Rav Gershon’s abode. Unusually for Charedi society, his explicit instruction was not heeded, and individuals and institutions alike continued to boycott Angel products until the bakery’s capitulation in the form of a letter of apology. Ironically, the letter was presented to Rav Gershon’s children at the Shiva house. Of course, the capitulation was celebrated by the Charedi press and politicians, and nobody even recalled Rav Gershon’s objection.

I believe Rav Gershon refused to see the demonstrators as “haters.” Frustrated Jews, perhaps, but still Jews – Jews with a deep core of goodness

But why did he object? Some will say that his refusal to support the boycott perpetuates Charedi weakness, part of an exilic ideology that repudiates power and prioritizes weakness, “keeping your head down,” not making noise. Charedi society, by contrast, has moved on from this mindset; if somebody attacks us, we know how to fight back. But perhaps there is more to it. I believe Rav Gershon refused to see the demonstrators as “haters.” Frustrated Jews, perhaps, but still Jews – Jews with a deep core of goodness. Perhaps he felt the boycott would only cause unnecessary alienation and friction and that this moment calls for national unity. Perhaps he understood that we should reserve such measures for harsh circumstances in which there is no option other than to fight.

Some will argue that Rav Gershon’s leadership departs from the accepted paradigm of Charedi leadership, which ought to be militant and uncompromising. This was the case made by the Jerusalem Faction against the leadership of Rav Aharon Leib Steinman zt”l, and it seems all the stronger concerning Rav Gershon zt”l.

Yet, it seems that after three generations of living in Israel, after phenomenal growth and unprecedented institutional development, this is the new direction of Charedi leadership. It is a leadership that predicates unity and cooperation. It is a leadership that allows ideas and initiatives to develop, bottom-up, from the Charedi field. And it is a leadership that allows Charedi society to step up to a place of deep responsibility for the entire Jewish People, engaging in sincere conversation with Jews outside its communities and seeking to formulate and execute the just and the good on a public and private level.

Hashem should provide us with leaders who follow the course that Rav Gershon began to pave. We need them.

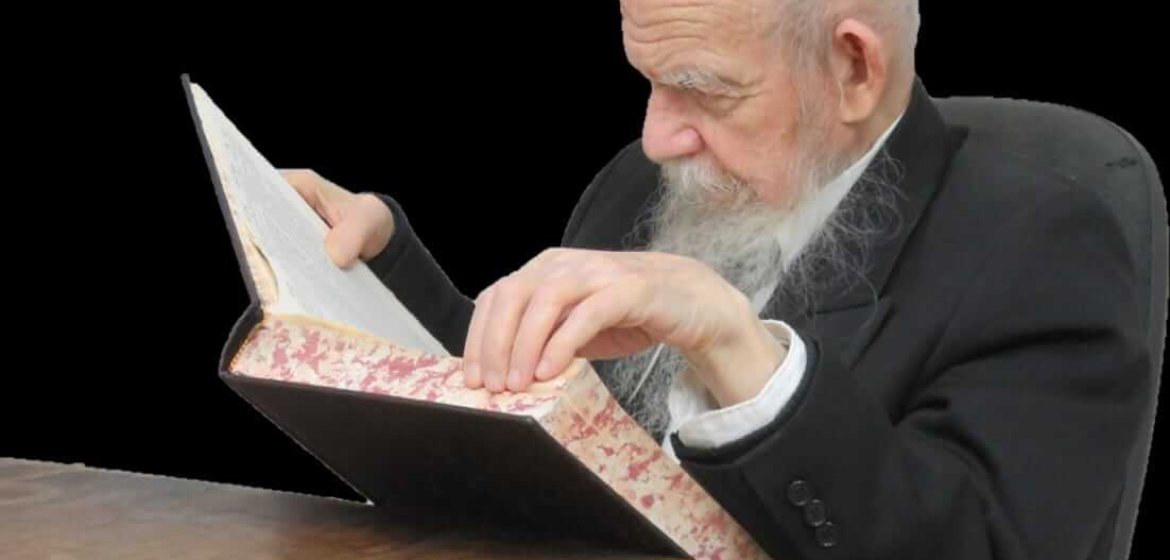

Photo: Bnei Brak, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

No rabbinic leader of recent times has embodied the message conveyed to Elisha to the degree Rav Gershon did.

It was said to Eliyahu, not Elisha.

Corrected. Thanks.

To look at Rabbi Edelstein, even in a photo, was to see incredible dignity, modesty and intelligence. He was the rarity, an aged sage whose mind was not diminished, and who was not surrounded – indeed imprisoned – by sycophants. crooks and family grifters. His views on education and acceptance flew in the face of the haredi zeitgeist, which may explain why he languished for so long in the shadows. One must hope and pray that his very belated public recognition will augur a shift in the prevailing mindset of most haredim, one of self-serving entitlement and indifference, if not outright hostility, to the greater society which sustains it.

Fabulous article. Just to mention:

1. R. Gershon was pretty harsh in his condemnation of secular studies, spoke about the World to Come of teachers etc.

2. He also had some statements that were certainly non-commonsensical, such as why Charedim get Covid-19 more than others (IIRC because they’re beholden to higher standards).

Thanks again